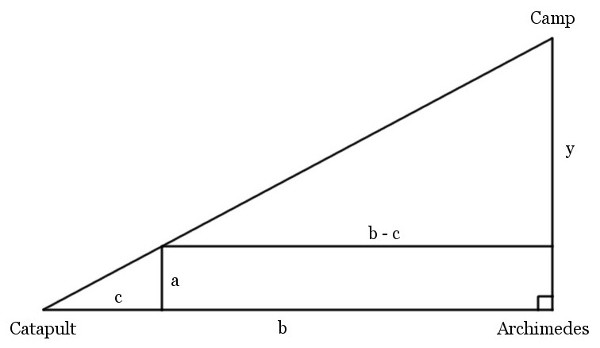

When violinist Hugh Gordon Langton was killed in World War I, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission inscribed a phrase of music (below, click to enlarge) on his headstone in Belgium’s Poelcapelle British Cemetery.

What the notes represent has been a mystery for more than a century. “They are not part of a tune that anyone has been able to discern and several have tried,” writes Sarah Wearne in Epitaphs of the Great War: Passchendaele. “In particular they are not from the song ‘After the Ball’ as some have suggested.”

Langton is the only casualty who was commemorated with a piece of music — the CWGC maintains more than a million graves and memorials worldwide, and only this one bears musical notes as an epitaph. If you can identify the tune, please contact the Commission.