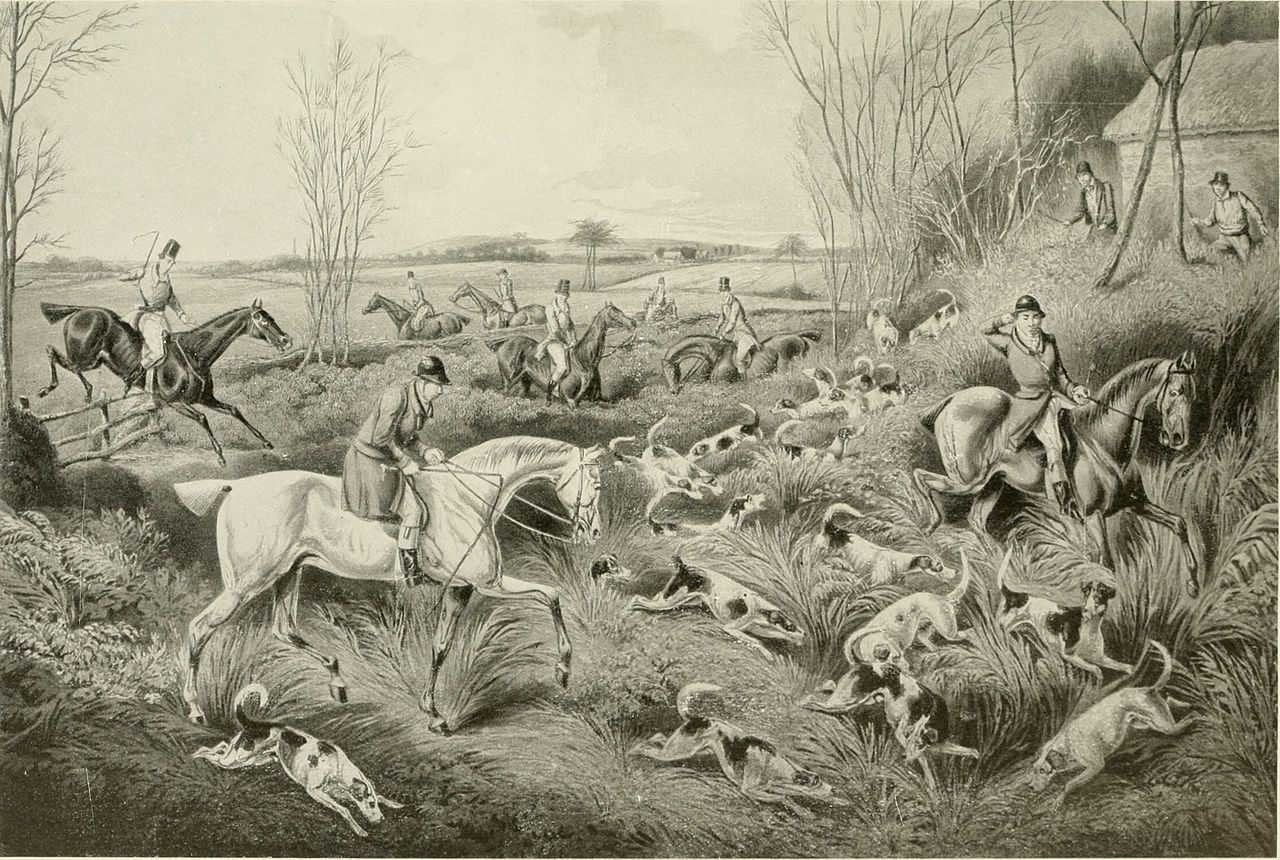

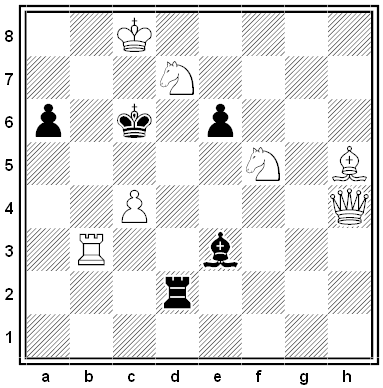

“The world may be divided into people that read, people that write, people that think, and fox-hunters.” — William Shenstone, “On Writing and Books,” 1769

“The world may be divided into people that read, people that write, people that think, and fox-hunters.” — William Shenstone, “On Writing and Books,” 1769

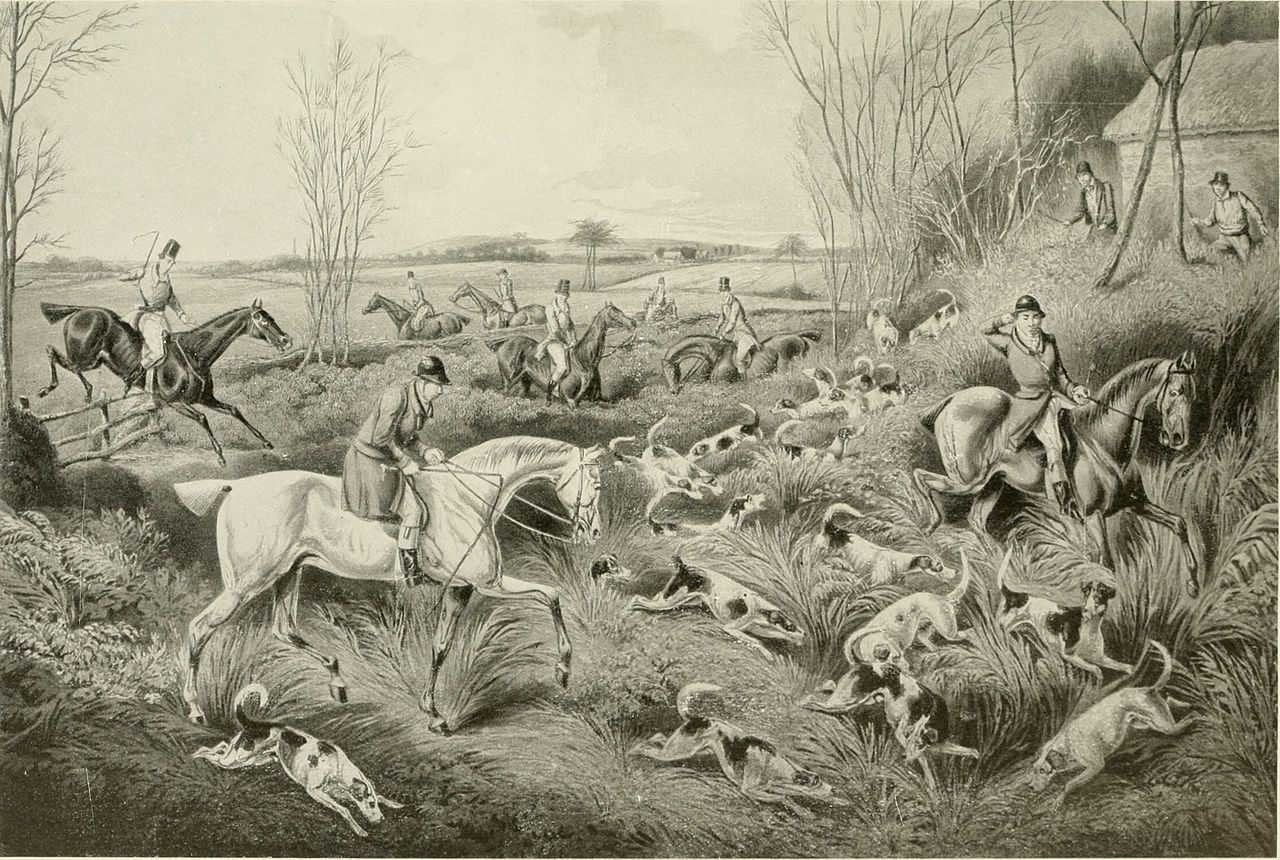

A problem proposed by Charles W. Trigg in the Spring 1970 issue of the Pi Mu Epsilon Journal (Volume 5, Number 4):

The digits 1-9 can be arranged in a square array so that the digits in no column, row, or long diagonal appear in order of magnitude:

Prove that, however this is done, the central digit must be odd.

In 1929 linguist Edward Sapir made up two words, mal and mil, and told 500 subjects that one of them meant “large table” and the other “small table.” When asked to tell which was which, 80 percent responded that mal meant “large table” and mil meant “small table” — suggesting that different vowels evoke different sizes.

Four years later, Stanley Newman extended the experiment to include all the vowels. He placed them in a sequence that he said English speakers associate with increasing sizes: i (as in ill), e (met), ae (hat), a (ah), u (moon), o (hole), and so on.

Interestingly, this ranking also reflects the size of the mouth shape needed to pronounce each vowel. “In other words,” writes Peter Farb in Word Play, “the psychological awareness that speakers of English have about what the vowels convey matches the anatomical means of producing them.”

(Edward Sapir, “A Study in Phonetic Symbolism,” Journal of Experimental Psychology 12:3 [1929], 225; Stanley S. Newman, “Further Experiments in Phonetic Symbolism,” American Journal of Psychology 45:1 [1933], 53-75.)

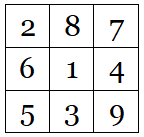

From Francis Healey, A Collection of Two Hundred Chess Problems, 1866. White to mate in two moves.

In 1928, when London’s Society of Model Engineers received word that the Duke of York would be unable to open its annual exhibition, acting secretary W.H. Richards said, “Very well, I will find a substitute: it is a mechanical show, let us have a mechanical man to open it.”

So they did. Attendees that September were greeted by a robot named Eric who could stand up, bow, look left and right, deliver a four-minute opening address “with appropriate gestures,” and sit down. The speech, imparted by a radio signal, was described as “really sparkling” — apparently literally, as blue sparks shot from Eric’s teeth. From the Model Engineer and Light Machinery Review:

The Exhibition of 1928 has been one of the most successful we ever had. … The ‘Robot’ was a continuous attraction; he drew thousands of people to see his remarkable performance. … It is estimated that he rose and bowed to his audiences more than a thousand times during the week, and he not only amused the majority of his visitors, but positively amazed and bewildered them with his clever movements and conversation.

In 1929 Eric toured America, where he visited Harvard and MIT and informed interviewers that he did not gamble, drink, or run around at night. That’s reassuring, because eventually he disappeared — London Science Museum curator Ben Russell told the Telegraph, “No one quite knows what happened to him, whether he was blown up or taken to pieces for spare parts.” So, working from old photographs, the museum rebuilt him, and he appeared, debonair as ever, in a 2017 exhibition:

In 1950, four patriotic Scots broke in to Westminster Abbey to steal the Stone of Scone, a symbol of Scottish independence that had lain there for 600 years. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow the memorable events of that evening and their meaning for the participants, their nation, and the United Kingdom.

We’ll also evade a death ray and puzzle over Santa’s correspondence.

Early Christian theologians had to contend with an awkward question: On Resurrection Day, what happens to people who have been devoured by birds, beasts, and fish? If the substance of my body has been assimilated by another creature, how can I reclaim it in eternity?

The answer came from Athenagoras in the second century. He declared that human flesh was “non-natural” and could not be absorbed by other creatures:

What is against nature can never pass into nourishment for the limbs and parts requiring it, and what does not pass into nourishment can never become united with that which it is not adapted to nourish. Then can human bodies never combine with bodies like themselves, to which this nourishment would be against nature, even though it were to pass many times through their stomach, owing to some most bitter accident.

Jonah, after all, had not been digested by the great fish that had swallowed him. So there was hope for those who had been devoured: They would be vomited or excreted, and God could then reassemble what he had once made.

This resolved the question, but it made for an unpleasant motif in Christian iconography in which beasts, birds, and fish vomit up feet, hands, limbs, and heads — the latter bearing happy faces.

(D. Endsjø, Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity, 2009.)

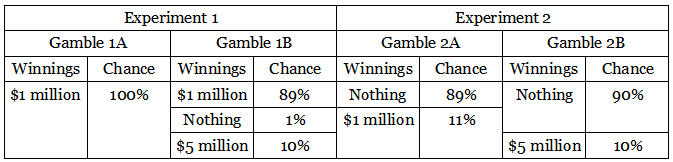

Consider two experiments — in each you’re asked to make a choice between two gambles:

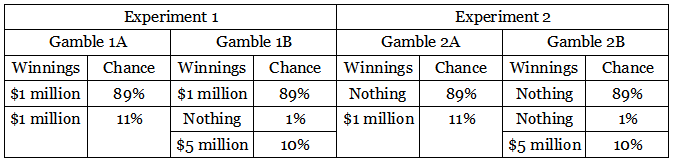

In the first experiment, most people choose Gamble 1A over Gamble 1B. In the second, most people choose Gamble 2B over Gamble 2A. Neither of those choices, in itself, is unreasonable. But economist Maurice Allais pointed out in 1953 that choosing 1A and 2B together does appear inconsistent. To see why, refine the table a bit further:

Now it’s clear that, within each experiment, both gambles give the same outcome 89 percent of the time. The only thing to distinguish them, then, is the remaining 11 percent — and when we focus on those segments, Gamble 1A matches Gamble 2A, and 1B matches 2B. Any given individual might tend to prefer a sure thing or a gamble, but here, it seems, most people prefer the sure thing in Experiment 1 and the gamble in Experiment 2.

This doesn’t mean that most people are irrational, Allais argued, but rather that expected utility theory might not reliably predict their behavior.

In a lecture at the University of Edinburgh in the 1970s, artificial intelligence pioneer I.J. Good pointed out that a robot cricket player doesn’t necessarily need a complex knowledge of physics in order to catch a ball — instead it might emulate humans, who follow a simple rule: “If the ball appears to be rising in the sky, run backwards. If it is falling, run towards it.”

Similarly, Hope College mathematician Tim Pennings noticed that his Welsh corgi, Elvis, seemed to follow the optimal path when chasing a ball thrown into Lake Michigan — Elvis seemed to realize that he ran faster than he swam, and so could minimize his retrieval time by racing intelligently along the beach before jumping into the water. But how did he make these judgments?

“We confess that although he made good choices, Elvis does not know calculus,” Pennings wrote. “In fact, he has trouble differentiating even simple polynomials.”

(Timothy J. Pennings, “Do Dogs Know Calculus?” College Mathematics Journal 34:3 [2003], 178-182.)