Author: Greg Ross

Unquote

“Everybody is somebody’s bore.” — Edith Sitwell

Good Boy

Discourage muggers during your evening dog walks with this “werewolf-style” muzzle, from Russia’s Zveryatam pet supply.

I wonder what other dogs make of this.

Tableau

A soul once cowered in a gray waste, and a mighty shape came by. Then the soul cried out for help, saying, ‘Shall I be left to perish alone in this desert of Unsatisfied Desires?’

‘But you are mistaken,’ the shape replied; ‘this is the land of Gratified Longings. And, moreover, you are not alone, for the country is full of people; but whoever tarries here grows blind.’

— Edith Wharton, The Valley of Childish Things, and Other Emblems, 1896

The Stable Marriage Problem

Given a group of 10 men and 10 women, all straight, is it always possible to pair them off in stable marriages, that is, to pair them so that there exist no man and woman who would prefer each other to the partners they have? Yes:

- In the first round, each man who’s not yet engaged proposes to the woman he most prefers. Then each woman says “maybe” to the suitor she most prefers and rejects all the others. Now she and the suitor she hasn’t rejected are provisionally engaged.

- In each following round, each man who’s not yet engaged proposes to the woman he most prefers and hasn’t yet approached. He does this even if she’s already engaged. Then each woman says “maybe” to her most preferred suitor, even if that means jilting her current provisional fiancé.

This process continues until everyone is engaged (as they must be, since every man must eventually propose to every woman and every woman must accept someone). All the marriages are stable because no man can end up pining for a woman who would prefer him to her own partner — that woman must already have rejected or jilted him at some point during the courting:

In 1962, mathematicians David Gale and Lloyd Shapley showed that stable marriages can always be found for any equal number of men and women.

Tact

When Robert Southey boasted to Richard Porson of the greatness of his poem Madoc, Porson answered:

“Madoc will be read when Homer and Virgil are forgotten.”

Podcast Episode 218: Lost in the Amazon

In 1769, a Peruvian noblewoman set out with 41 companions to join her husband in French Guiana. But a series of terrible misfortunes left her alone in the Amazon jungle. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow Isabel Godin des Odonais on her harrowing adventure in the rain forest.

We’ll also learn where in the world “prices slippery traps” is and puzzle over an airport’s ingenuity.

Line Limit

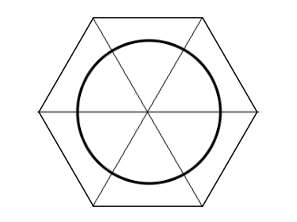

You own a goat and a meadow. The meadow is in the shape of an equilateral triangle each side of which is 100 meters long. The goat is tied to a post at one corner of the meadow. How long should you make the tether in order to give the goat access to exactly half the meadow?

An Actor’s Notes

Ellen Terry played Juliet at London’s Lyceum Theatre in 1882. The following was later found on the flyleaf of her copy of the text:

Get the words into your remembrance first of all. Then, (as you have to convey the meaning of the words to some who have ears, but don’t hear, and eyes, but don’t see) put the words into the simplest vernacular. Then exercise your judgment about their sound.

So many different ways of speaking words! Beware of sound and fury signifying nothing. Voice unaccompanied by imagination, dreadful. Pomposity, rotundity.

Imagination and intelligence absolutely necessary to realize and portray high and low imaginings. Voice, yes, but not mere voice production. You must have a sensitive ear, and a sensitive judgment of the effect on your audience. But all the time you must be trying to please yourself.

Get yourself into tune. Then you can let fly your imagination, and the words will seem to be supplied by yourself. Shakespeare supplied by oneself! Oh!

Realism? Yes, if we mean by that real feeling, real sympathy. But people seem to mean by it only the realism of low-down things.

To act, you must make the thing written your own. You must steal the words, steal the thought, and convey the stolen treasure to others with great art.

(From Donald Sinden, ed., The Everyman Book of Theatrical Anecdotes, 1987.)

Time Saver

Ogden Nash invented a streamlined limerick he called the “limick”:

An old person of Troy

In the bath is so coy

That it doesn’t know yet

If it’s a girl or a boy.

Two nudists of Dover,

When purple all over,

Were munched by a cow,

When mistaken for clover.

A cook called McMurray

Got a raise in a hurry

From his Hindu employer,

By flavouring curry.

A young flirt of Ceylon,

Who led the boys on,

Playing “Follow the Leda,”

Succumbed to a swan.