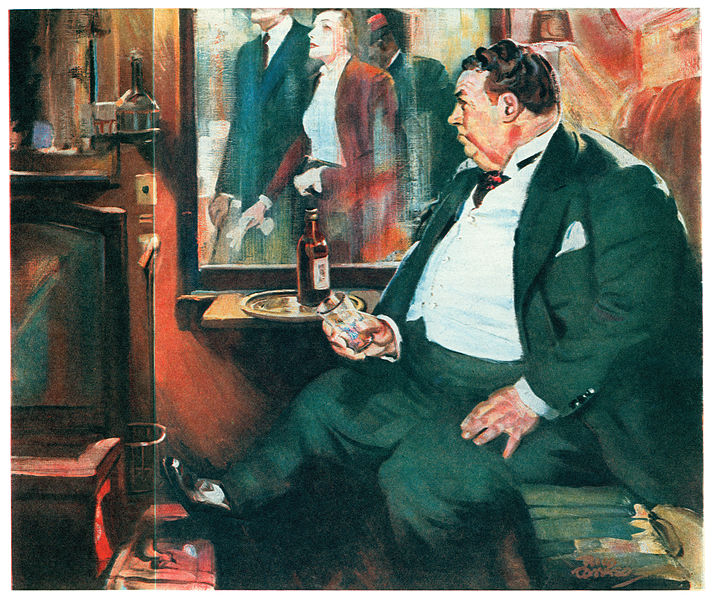

In Rex Stout’s mystery novels, detective Nero Wolfe maintains that he was born in Montenegro, but the stories give conflicting evidence, and after careful study historian Bernard DeVoto concluded that he was really born in the United States sometime between 1892 and 1896, having been conceived in Montenegro between March 1891 and March 1895.

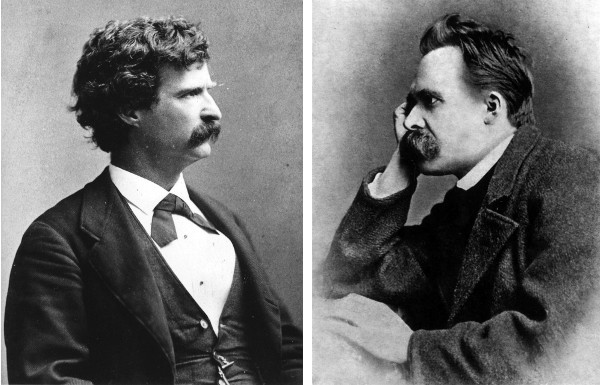

Now, Sherlock Holmes had his climactic battle with Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Fall at the beginning of May 1891, after which he disappeared into shadowy wanderings until 1894. Writer John D. Clark notes that Holmes could easily have visited Cetinje and remained there for several months, long enough to meet Irene Adler, whose fragile marriage would by then have broken up, sending her back to an itinerant life as an opera singer. The two would naturally have fallen in together, especially as English speakers were relatively rare in Montenegro, and an eventual affair was inevitable.

When Adler became pregnant she would have returned to her parents in New Jersey and given birth there. Nero Wolfe was born in New Jersey in late 1892 or early 1893, six months after Adler would had left Montenegro. She would then have returned to Central Europe, where her son grew up, just as he states. Clark concludes, “Whether Wolfe ever condescends to admit it, or whether he remains forever silent, his parentage can no longer be a matter of conjecture, nor can there be any doubt as to the source from which he inherited his remarkable talents.”

In 1955 Clark put this case to Stout, who responded with this note:

I am obliged to you for sending me the ms. for perusal, and I admire the finesse of your suggestion that ‘censorship’ by me might be desirable and acceptable. As the literary agent of [Wolfe’s assistant] Archie Goodwin I am of course privy to many details of Nero Wolfe’s past which to the general public, and even to scholars of Clark’s standing, must remain moot for some time. If and when it becomes permissible for me to disclose any of those details, your distinguished journal would be a most appropriate medium for the disclosure. The constraint of my loyalty to my client makes it impossible for me to say more now.

He never fully denied the theory. He died in 1975.

(John D. Clark, “Some Notes Relating to a Preliminary Investigation Into the Paternity of Nero Wolfe,” Baker Street Journal, January 1956.)