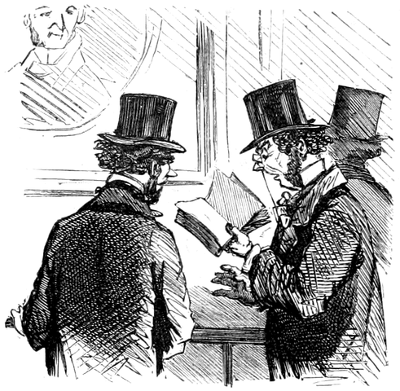

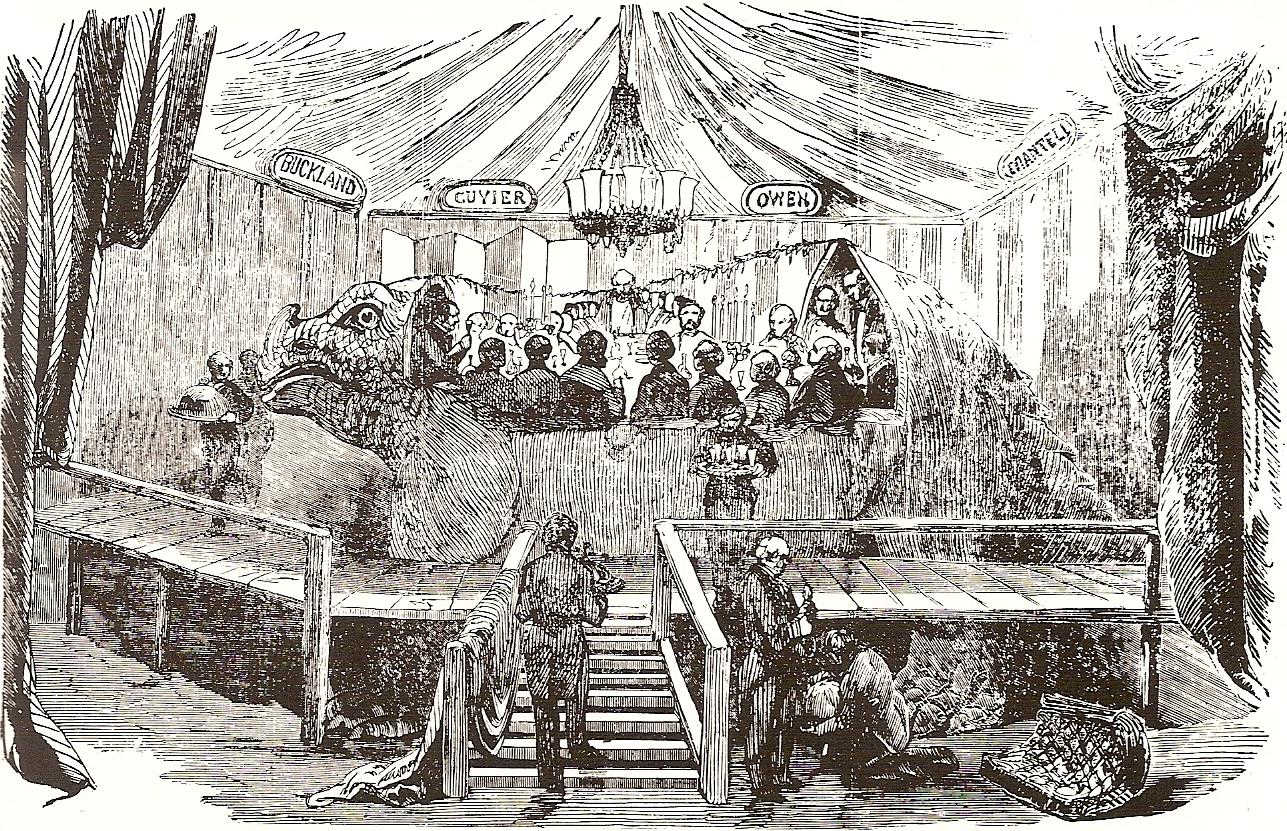

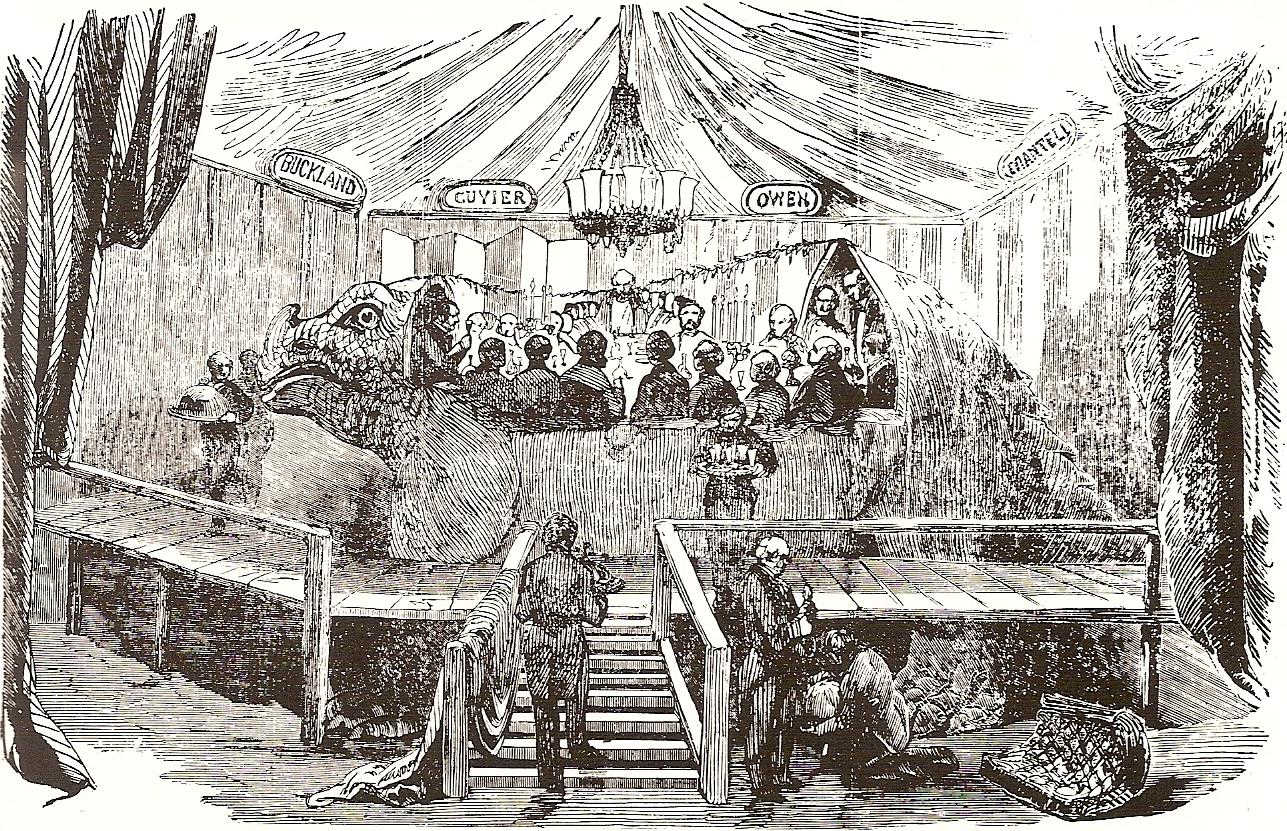

In 1852, British artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins engaged to make 33 life-size concrete models of extinct dinosaurs, to be arranged in a park in southern London around the relocated Crystal Palace. Throughout the work he conferred with a team of leading British scientists, and on New Year’s Eve 1853 they celebrated their accomplishment with a dinner party held inside one of the sculptures:

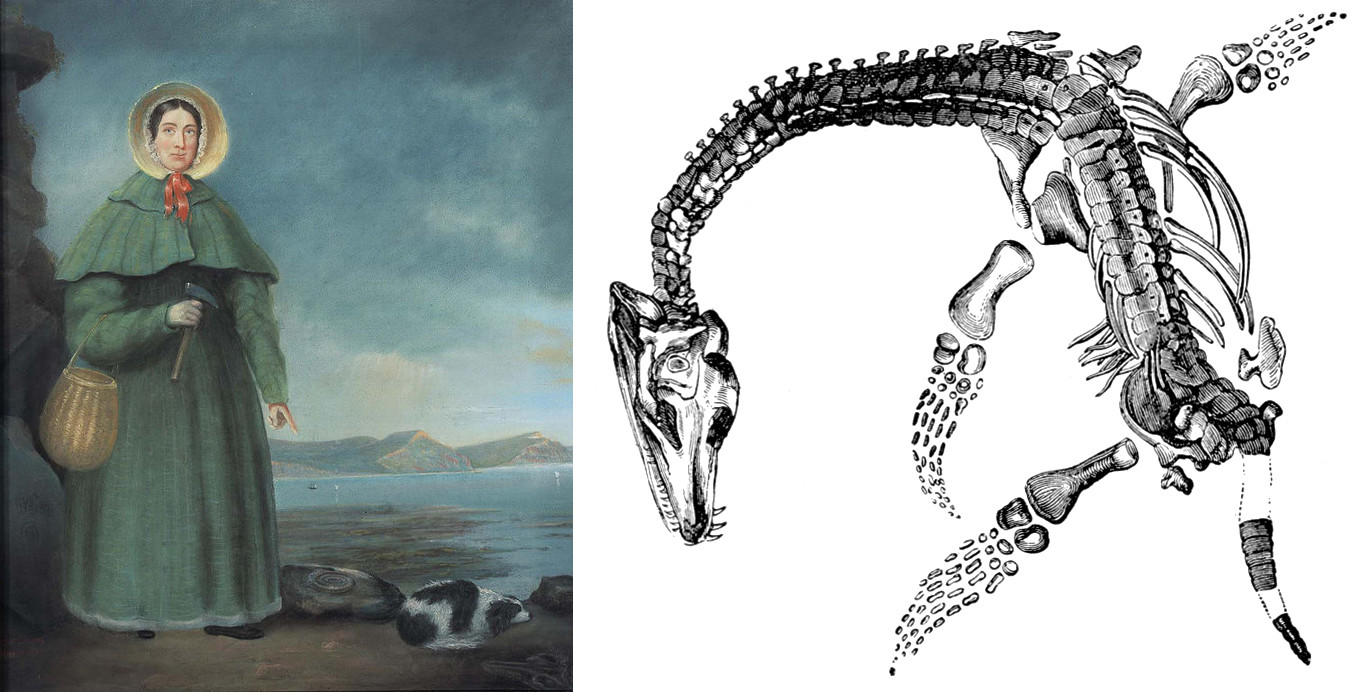

Twenty-one of the guests were accommodated with seats ranged on each side of the table, within the sides of the iguanodon. Professor Owen, one of the most eminent geologists of the day, occupied a seat at the head of the table, and within the skull of the monster. Mr. Francis Fuller, the Managing Director, and Professor Forbes, were seated on commodious benches placed in the rear of the beast. An awning of pink and white drapery was raised above the novel banqueting-hall, and small banners bearing the names of Conybeare, Buckland, Forbes, Owen, Mantell, and other well-known geologists, gave character and interest to the scene. When the more substantial viands were disposed of, Professor Owen proposed that the company should drink in silence ‘The memory of Mantell, the discoverer of the iguanodon,’ the monster in whose bowels they had just dined.

They concluded with a “roaring chorus” in praise of the “antediluvian dragon”:

A thousand ages underground

His skeleton had lain;

But now his body’s big and round,

And he’s himself again!

His bones, like Adam’s, wrapped in clay,

His ribs of iron stout,

Where is the brute alive to-day

That dares with him turn out?

Beneath his hide he’s got inside

The souls of living men,

Who dare our Saurian now deride

With life in him again?

(Chorus) The jolly old beast

Is not deceased,

There’s life in him again. (A roar.)

In fairy land are fountains gay,

With dragons for their guard:

To keep the people from the sight,

The brutes hold watch and ward!

But far more gay our founts shall play,

Our dragons, far more true,

Will bid the nations enter in

And see what skill can do!

For monsters wise our saurians are,

And wisely shall they reign,

To spread sound knowledge near and far

They’ve come to life again!

Though savage war her teeth may gnash,

And human blood may flow,

And foul ambition, fierce and rash,

Would plunge the world in woe,

Each column of this palace fair

That heavenward soars on high,

A flag of hope shall on it bear,

Proclaiming strife must die!

And art and science far shall spread

Around this fair domain,

The People’s Palace rears its head

With life in it again.

(From Routledge’s Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park at Sydenham, 1854.)