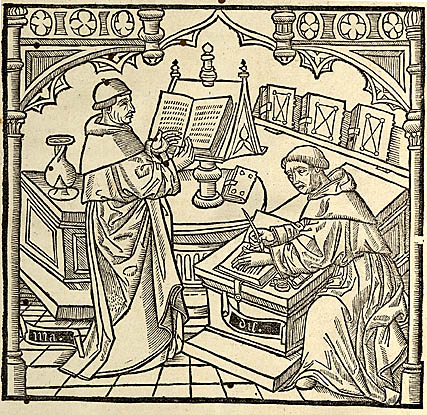

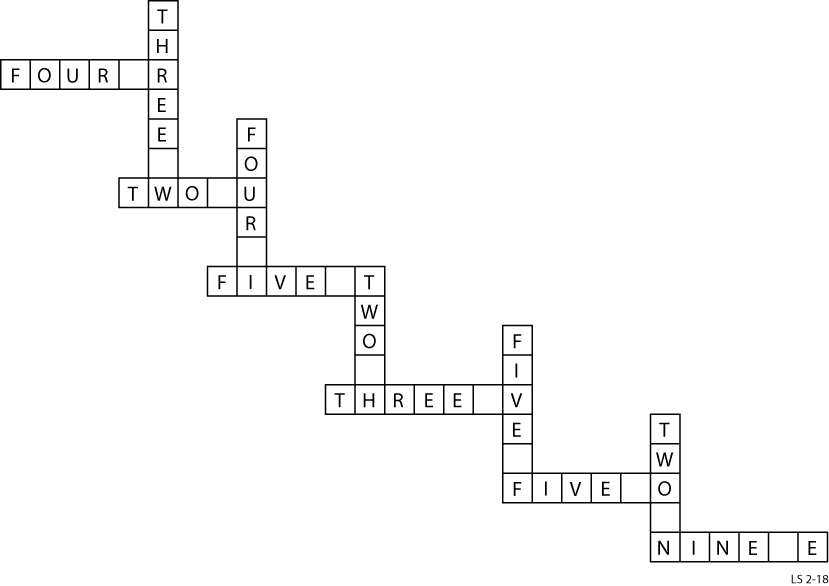

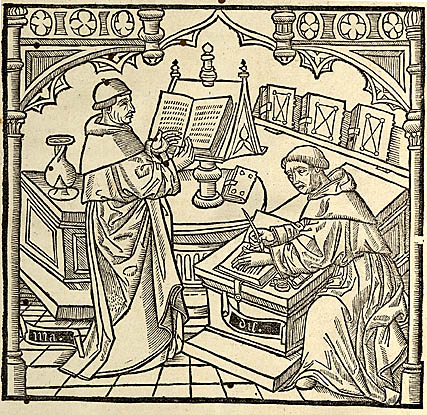

Notes left in manuscripts and colophons by medieval scribes and copyists, from the Spring 2012 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly:

New parchment, bad ink; I say nothing more.

I am very cold.

That’s a hard page and a weary work to read it.

Let the reader’s voice honor the writer’s pen.

This page has not been written very slowly.

The parchment is hairy.

The ink is thin.

Thank God, it will soon be dark.

Oh, my hand.

Now I’ve written the whole thing; for Christ’s sake give me a drink.

Writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back, it dims your sight, it twists your stomach and your sides.

St. Patrick of Armagh, deliver me from writing.

While I wrote I froze, and what I could not write by the beams of the sun I finished by candlelight.

As the harbor is welcome to the sailor, so is the last line to the scribe.

This is sad! O little book! A day will come in truth when someone over your page will say, “The hand that wrote it is no more.”

In her History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting, Anne Trubek lists another: “Here ends the second part of the title work of Brother Thomas Aquinas of the Dominican Order; very long, very verbose, and very tedious for the scribe.”