Alfred Hitchcock’s 1945 film Spellbound was shot in black and white, but the conclusion contains two frames of red when a gun is fired (1:54:40 above).

(This involves a big spoiler, so don’t click if you haven’t seen the movie.)

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1945 film Spellbound was shot in black and white, but the conclusion contains two frames of red when a gun is fired (1:54:40 above).

(This involves a big spoiler, so don’t click if you haven’t seen the movie.)

Is it possible for someone who has had no musical training whatsoever, and who has never learned the names of the notes, to be known by others to have absolute pitch? The answer is YES! I knew a police officer who was totally unmusical, and never knew the names of the notes, who nevertheless was known to have absolute pitch. How? Well, this was eighty-five years ago, when police stations emitted radio signals, each station having its own individual frequency. The police officer in question was the only one among his fellow officers who upon hearing the radio signal could identify the police station!

— Raymond Smullyan, Reflections, 2015

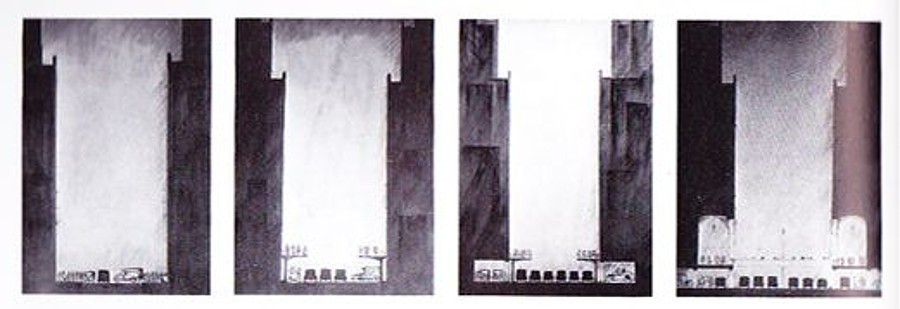

French artist Georges Rousse photographs anamorphic images in abandoned and derelict buildings.

When the scene above is viewed from the right vantage point, it looks like this:

This video shows him at work on a project in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan, in 2013:

At a 1931 costume ball, seven New York architects appeared as their own buildings. Left to right: A. Stewart Walker as the Fuller Building; Leonard Schultze as the Waldorf-Astoria; Ely Jacques Kahn as the Squibb Building; William Van Alen as the Chrysler Building; Ralph Walker as One Wall Street; D.E. Ward as the Metropolitan Tower; and Joseph H. Freedlander as the Museum of the City of New York.

That’s from Rem Koolhaas’ Delirious New York, 1994. Some compromises: Freedlander had never designed a skyscraper, so he put the museum on his head. Schultze had to represent the twin-towered Waldorf Astoria with a single headdress. And “The elegant top of A. Stewart Walker’s Fuller Building has so few openings that faithfulness to its design now condemns its designer to temporary blindness.”

William Van Alen, in the center, went bananas with the Chrysler Building: The headpiece is an exact facsimile of the top of the building; the cape, puttees, and cuffs are made of flexible wood selected from trees in India, Australia, the Philippines, South America, Africa, Honduras, and North America; the cape matches the design of the first floor elevator doors, using the correct woods; the front is a replica of the elevator doors on the upper floors of the building; and the shoulder ornaments are the eagles’ heads that appear at the building’s 61st-floor setback.

One marvel I couldn’t find a photo of: Thomas Gillespie “dressed as a void to represent an unnamed subway station.”

Here’s a lost art: “Ceiling walking” was a popular form of American entertainment as early as 1806, when “Sanches, the Wonderful Antipodean” wore iron shoes that were “fitted in grooves in a board fastened to the top of the stage.”

Spectacles such as this were drawing crowds right through the 19th century. In New Orleans in the 1880s a young “human fly” named Mademoiselle Aimee was carried by her teeth to a trapeze 50 feet in the air, from which she affixed her feet to the ceiling by some indistinct means. “Many such exclamations as ‘My God!’ ‘Oh My!’ and so on follow, and as she puts one foot before the other, walking in a forward direction, the situation is most thrilling,” marveled the Daily Picayune. “Often ladies have fainted at the sight of the almost child’s peril, and men have trembled while looking up at her. Many refuse to look up at all and those who do continue to look are in constant apprehension of a terrible accident. There is no question in the world but that the feat is without parallel in the matter of tempting fate.”

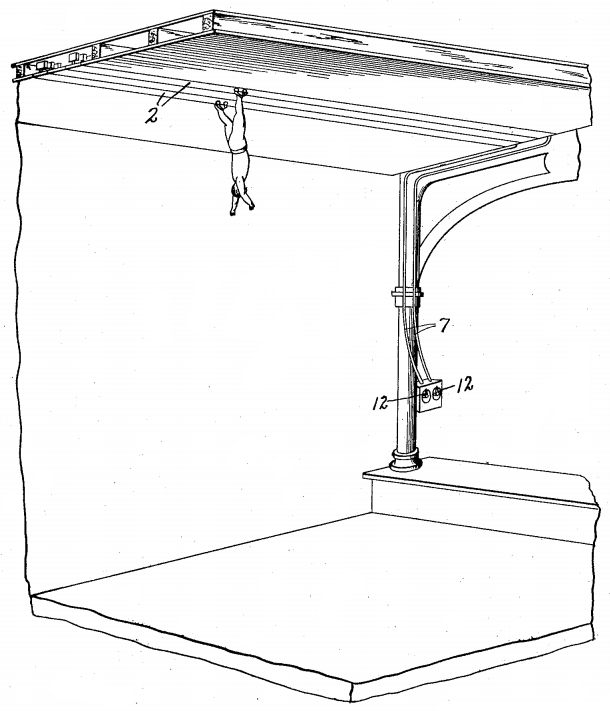

How was this done? There seem to be a range of answers. V. Waid’s “Theatrical Device” of 1905 used vacuum cups attached to the fly’s feet, but both E.I. George’s “Electric Aerial Ambulating System” of 1909 (above) and C.H. Newman and W. Berrigan’s “Electrical Device to Enable Showmen to Walk on the Ceiling” of 1885 used electromagnets.

How would this have evolved if it had remained popular? What would we be using today?

(From Jacob Smith, The Thrill Makers, 2012.)

accinge

v. to prepare or apply oneself

facetely

adv. elegantly; cleverly; ingeniously

plusquamperfection

n. utter perfection

magnality

n. a great or wonderful thing

A villainous Nazi named Roehm

Was searching for rhymes matching “poem.”

Then, chortling with glee,

Stated that he

Had found one at last. “That’ll show ’em!”

— J.M. Crais

In 1923 Columbia University architect Harvey Wiley Corbett proposed a novel solution to Manhattan’s traffic problem: surrender. His Proposals for Relieving Traffic Congestion in New York had four phases:

Corbett took a strangely romantic view of this: “The whole aspect becomes that of a very modernized Venice, a city of arcades, plazas and bridges, with canals for streets, only the canals will not be filled with real water but with freely flowing motor traffic, the sun glistening on the black tops of the cars and the buildings reflecting in this waving flood of rapidly rolling vehicles.”

By 1975, Corbett wrote, Manhattan could be a network of 20-lane streets in which pedestrians walk from “island” to “island” in a “system of 2,028 solitudes.” That doesn’t feel so different from what we have today.

Related: The city of Guanajuato, Mexico, is built on extremely irregular terrain, and many of the streets are impassable to cars. To compensate, the residents have converted underground drainage ditches and tunnels into roadways (below). These had been dug for flood control during colonial times, but modern dams have left them dry. (Thanks, David.)

All [J. Smith] ever paints are pastoral landscapes. But years after Smith’s Lake Placid is bought and exhibited by a very conservative museum, an art critic discovers that by tilting the painting 90 degrees, it can be seen as a painting of a devil embracing two nudes. The critic calls this aspect Ménage. The enraged artist protests that he had never intended to paint the lewd picture, that his painting is a realistic representation of Lake Placid and nothing more, and that the critic’s interpretation is illegitimate.

Is Ménage a work of art? If so, is it a work by Smith? Can Ménage be a better painting than Lake Placid (or vice versa)? Or is this painting neither Lake Placid nor Ménage? Would you, as the conservative curator, remove the painting?

— Eddy Zemach of Hebrew University, Jerusalem, posed in Margaret P. Battin et al., Puzzles About Art, 1989

In 1835, a Native American woman was somehow left behind when her dwindling island tribe was transferred to the California mainland. She would spend the next 18 years living alone in a world of 22 square miles. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the poignant story of the lone woman of San Nicolas Island.

We’ll also learn about an inebriated elephant and puzzle over an unattainable test score.