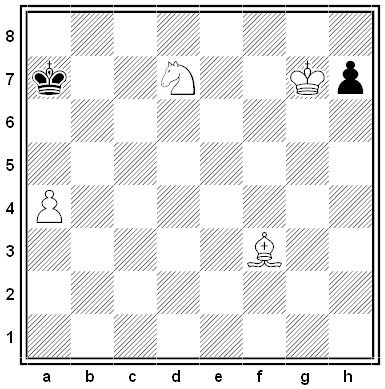

In 2004, engineers Richard Clements and Roger Hughes put their study of crowd dynamics to an unusual application: the medieval Battle of Agincourt, which pitted Henry V’s English army against a numerically superior French army representing Charles VI. In their model, an instability arises on the front between the contending forces, which may account for the relatively large proportion of captured soldiers:

[P]ockets of French men-at-arms are predicted to push into the English lines and with hindsight be surrounded and either taken prisoner or killed. … Such an instability might explain the victory by the weaker English army by surrounding groups of the stronger army.

This description is consistent with the three large mounds of fallen soldiers that are reported in contemporary accounts of the battle. If the model is accurate then perhaps French men-at-arms succeeded in pushing back the English in certain locations, only to be surrounded and slaughtered, rallying around their leaders. By contrast, modern accounts perhaps incorrectly describe a “wall” of dead running the length of the field.

“Interestingly, the study suggests that the battle was lost by the greater army, because of its excessive zeal for combat leading to sections of it pushing through the ranks of the weaker army only to be surrounded and isolated.” The whole paper is here.

(Richard R. Clements and Roger L. Hughes. “Mathematical Modelling of a Mediaeval Battle: The Battle of Agincourt, 1415,” Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 64:2 [2004], 259-269.)