In 1941, the BBC established an Eastern Services Committee to discuss programming in India. The meetings were held in Room 101 at 55 Portland Place in London. George Orwell attended at least 12 meetings there and was asked to convene a subcommittee to consider organizing drama and poetry competitions.

Orwell scholar Peter Davison writes, “In Nineteen Eighty-Four O’Brien tells Orwell that the thing that is in Room 101 is the worst thing in the world. The understandable impression is that this is something like drowning, death by fire, or impalement, but Orwell is more subtle: for many, and for him, the worst thing in the world is that which is the bureaucrat’s life-blood: attendance at meetings.”

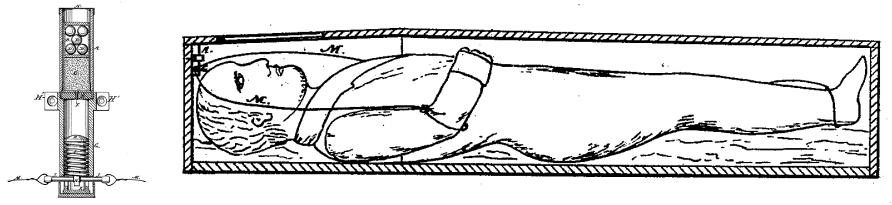

In 2003, when the original building was scheduled to be demolished, artist Rachel Whiteread made a plaster cast of the room’s interior (above). It was displayed in the Victoria and Albert Museum later that year.

(From George Orwell: A Life in Letters, 2013.)