203313 × 657624 = 426756 × 313302

Author: Greg Ross

In a Word

tenue

n. bearing, deportment

ogganition

n. snarling

A peculiar detail from the Battle of Waterloo:

As the day wore on, the French cavalry became more and more desperate, and charged repeatedly with fierce gesticulations, which became more pronounced as they were so continuously repelled. These peculiar looks and gestures of the French became so marked that when the colonel, Fielding Browne, gave the familiar order, ‘Prepare for cavalry,’ the officers would thunder out the order, and add, ‘Now, men, make faces!’

(“The Prince of Wales’s Volunteers,” Navy & Army Illustrated, Feb. 4, 1899.)

Open Secrets

In the 1850s, lovers often corresponded by printing coded messages in the Times. An example from February 1853:

CENERENTOLA. N bnxm yt ywd nk dtz hfs wjfi ymnx fsi fr rtxy fschtzx yt. Mjfw ymf esi, bmjs dtz wjyzws fei mtb qtsldtz wjrfns, ncjwj. lt bwnyf f kjb qnsjx jfuqnsl uqjfxy. N mfaj xnsbj dtz bjsy fbfd.

(“I wish to try if you can read this and am most anxious to hear that and when you return and how long you remain here. Go write a few lines explaining please. I have since you went away.”)

A second message appeared nine days later using the same cipher:

CENERENTOLA. Zsyng rd n jtwy nx xnhp mfaj n y wnj, yt kwfrj fs jcugfifynts ktw dtz lgzy hfssty. Xnqjshj nx nf jny nk ymf ywzj bfzxy nx sty xzx jhyji; nk ny nx, fgg xytwpjx bngg gj xnkyji yt ymjgtyytr. It dtz wjrjgjw tzw htzxns’x knwxy nwtutxnynts: ymnsp tk ny. N pstb Dtz.

(“Until my heart is sick I have tried to frame an explanation for you but cannot. Silence is safest if the true cause is not suspected; if it is, all stories will be sifted to the bottom. Do remember our cousin’s first proposition. Think of it. I know you.”)

This practice was so well known that cracking the codes became a regular recreation among certain Londoners. Lyon Playfair and Charles Wheatstone uncovered a pending elopement and wrote a remonstrating response to the young woman; she published a new message saying, “Dear Charles, write me no more, our cipher is discovered.”

Most of the messages were simple substitution ciphers, which made them fairly easy to solve, though the lovers seemed to find them challenging — one wrote, “If an honours degree at Oxford cannot read my message, we had better change the cipher. Suggest we revert to numbers. Love, Gwendoline.” But when Playfair and Wheatstone came up with a more secure “symmetrical cipher” and offered it to the Foreign Office, the under-secretary rejected it as “too complicated.”

“We proposed that he should send for four boys from the nearest elementary school,” Playfair wrote, “in order to prove that three of them could be taught to use the cipher in a quarter of an hour. The reply to this proposal by their Under-Secretary was … ‘That is very possible, but you could never teach it to attachés.'”

(From Donald McCormick, Love in Code, 1980. Here’s a whole book of messages, both coded and clear.)

Love and Laureates

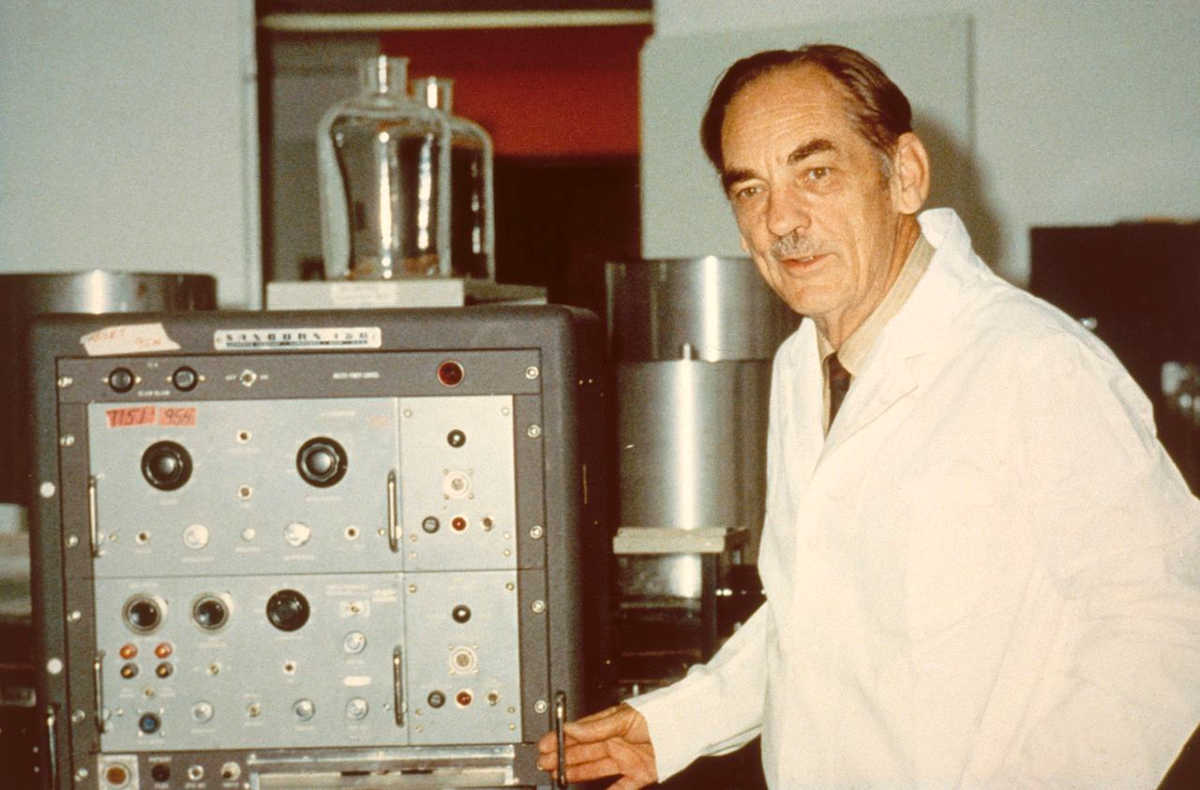

George Hitchings, who won the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1988, proposed to his wife by saying “Incidentally, you’re my fiancée now” as they drove to an event.

John Bardeen, who won the prize in physics in both 1956 and 1972, told his fiancée, “You can be married in the church if you want to, but not to me.”

Hemingway, a Nobelist in literature in 1954, said, “I remember after I got that marriage license I went across from the license bureau to a bar for a drink. The bartender said, ‘What will you have, sir?’ And I said, ‘A glass of hemlock.'”

And Wolfgang Pauli won the Nobel in physics in 1945. Of his ex-wife’s remarriage, he said, “Had she taken a bullfighter I would have understood, but an ordinary chemist!”

Fenceposts

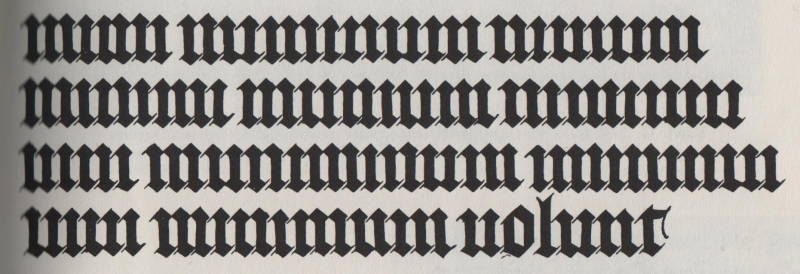

To show that Gothic script could be fatiguing to read, medieval scribes invented this joke sentence:

mimi numinum niuium minimi munium nimium uini muniminum imminui uiui minimum uolunt

The snow gods’ smallest mimes do not wish in any way in their lives for the great duty of the defenses of wine to be diminished.

In Ancient Writing and Its Influence (1969), Berthold Louis Ullman and Julian Brown write, “When this is written in Gothic characters without dots for the i‘s and with v written as u, it makes a first-class riddle”:

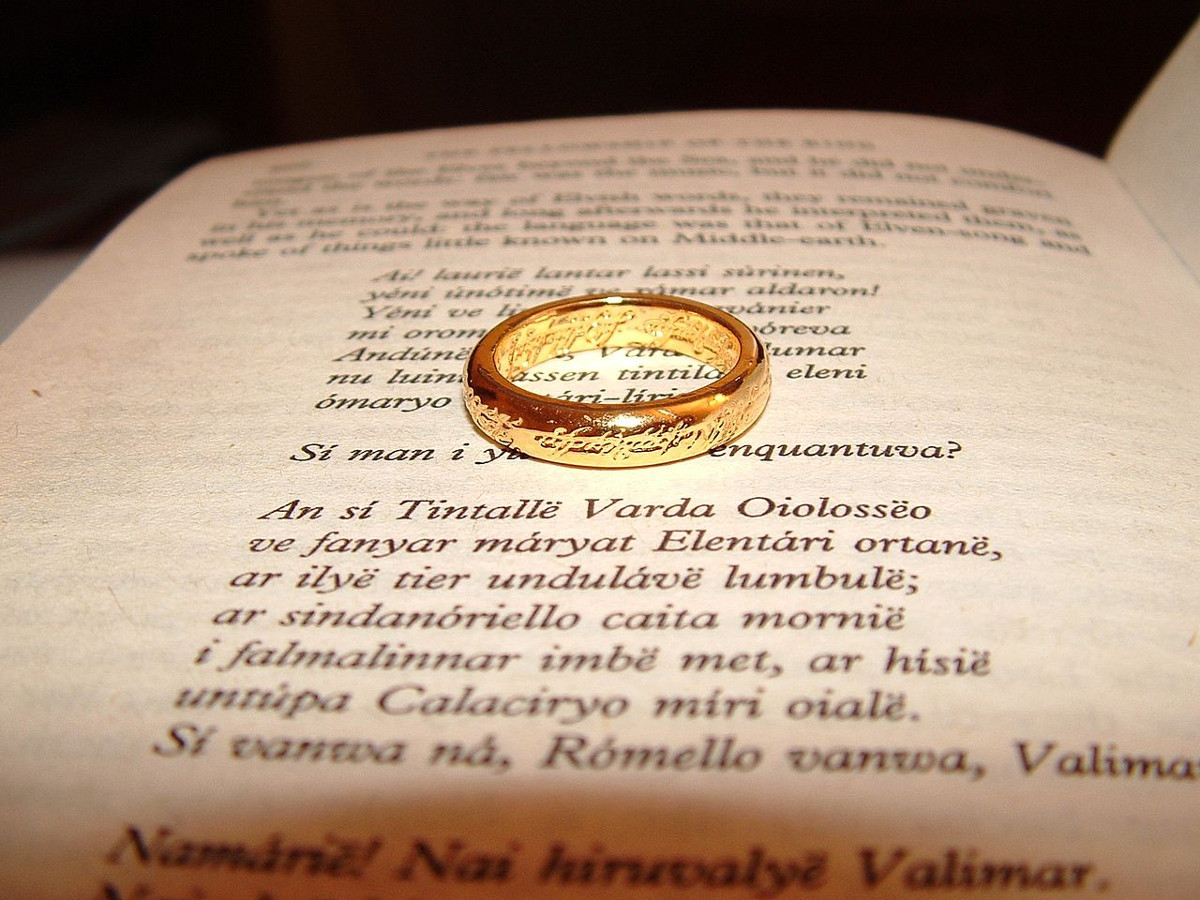

The War of the Ring

Of The Lord of the Rings, W.H. Auden wrote, “I rarely remember a book about which I have had such violent arguments. Nobody seems to have a moderate opinion: either, like myself, people find it a masterpiece of its genre or they cannot abide it.”

Among the naysayers, Edmund Wilson wrote, “One is puzzled to know why the author should have supposed he was writing for adults. There are, to be sure, some details that are a little unpleasant for a children’s book, but except when he is being pedantic and also boring the adult reader, there is little in The Lord of the Rings over the head of a seven-year-old child.”

Tolkien seemed philosophical about the difference. He wrote in the foreword to the second edition:

The prime motive was the desire of a tale-teller to try his hand at a really long story that would hold the attention of readers, amuse them, delight them, and at times maybe excite them or deeply move them. As a guide I had only my own feelings for what is appealing or moving, and for many the guide was inevitably often at fault. Some who have read the book, or at any rate have reviewed it, have found it boring, absurd, or contemptible; and I have no cause to complain, since I have similar opinions of their works, or of the kinds of writing that they evidently prefer.

He wrote elsewhere:

The Lord of the Rings

is one of those things:

if you like it you do:

if you don’t, then you boo!

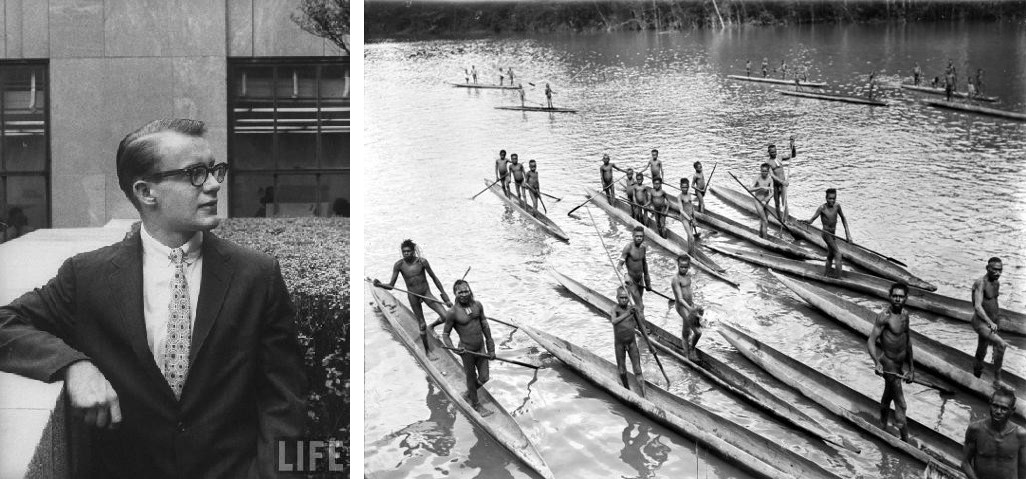

Podcast Episode 112: The Disappearance of Michael Rockefeller

In 1961, Michael Rockefeller disappeared after a boating accident off the coast of Dutch New Guinea. Ever since, rumors have circulated that the youngest son of the powerful Rockefeller family had been killed by the headhunting cannibals who lived in the area. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast, we’ll recount Rockefeller’s story and consider the different fates that might have befallen him.

We’ll also learn more about the ingenuity of early sportscasters and puzzle over a baffled mechanic.

The Tipping Point

English meteorologist Lewis Fry Richardson (1881-1953) spent the last 25 years of his life trying to establish a mathematical theory of the causes of war. In the first of two books on this subject, Arms and Insecurity, he works out a model of arms races using differential equations and reaches the conclusion that

where:

U and V are the annual defense budgets of two parties to a conflict

k is a positive constant representing the response to threat

α is a positive constant representing the fatigue and expense of keeping up defenses

U0 and V0 represent cooperations between the parties, tentatively assumed to remain constant

and g and h represent the “grievances and ambitions, provisionally regarded as constant,” on each side.

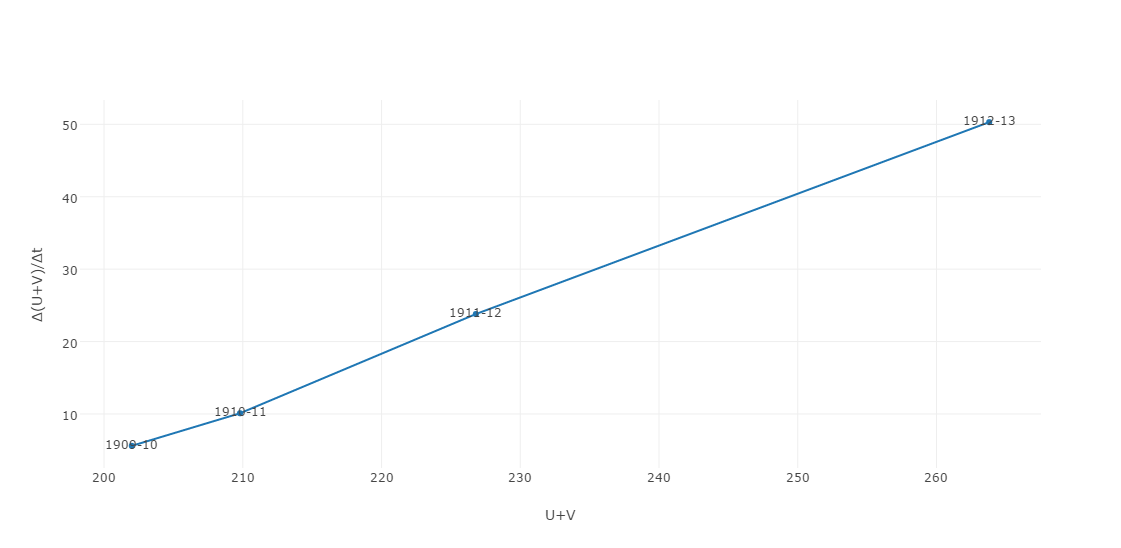

The term in brackets is a constant, so Richardson predicted that plotting d(U + V)/dt against (U + V) would produce a straight line. He tried this out using the defense budgets of the Franco-Russian and Austro-German alliances for 1909-14 and got this:

“The four points lie close to a straight line, closer, indeed, than one might expect,” he writes. “Since I first drew this diagram, which was shown at the British Association in Cambridge in 1938, and printed in Nature of 29 October of that year, I have been incredulous about the marvelously good fit. Yet there is no simple mistake. … The mere regularity of these phenomena shows that foreign politics had then a rather machine-like quality, intermediate between the predictability of the moon and the freedom of an unmarried young man.”

The extrapolated straight line hits the x axis at U + V = £194 pounds sterling. “As love covereth a multitude of sins, so the good will between the opposing alliances would just have covered £194 million of defense expenditures on the part of the four nations concerned. Their actual expenditure in 1909 was £199 millions; and so began an arms race which led to World War I.”

(Lewis F. Richardson, Arms and Insecurity, 1949.)

Presence of Mind

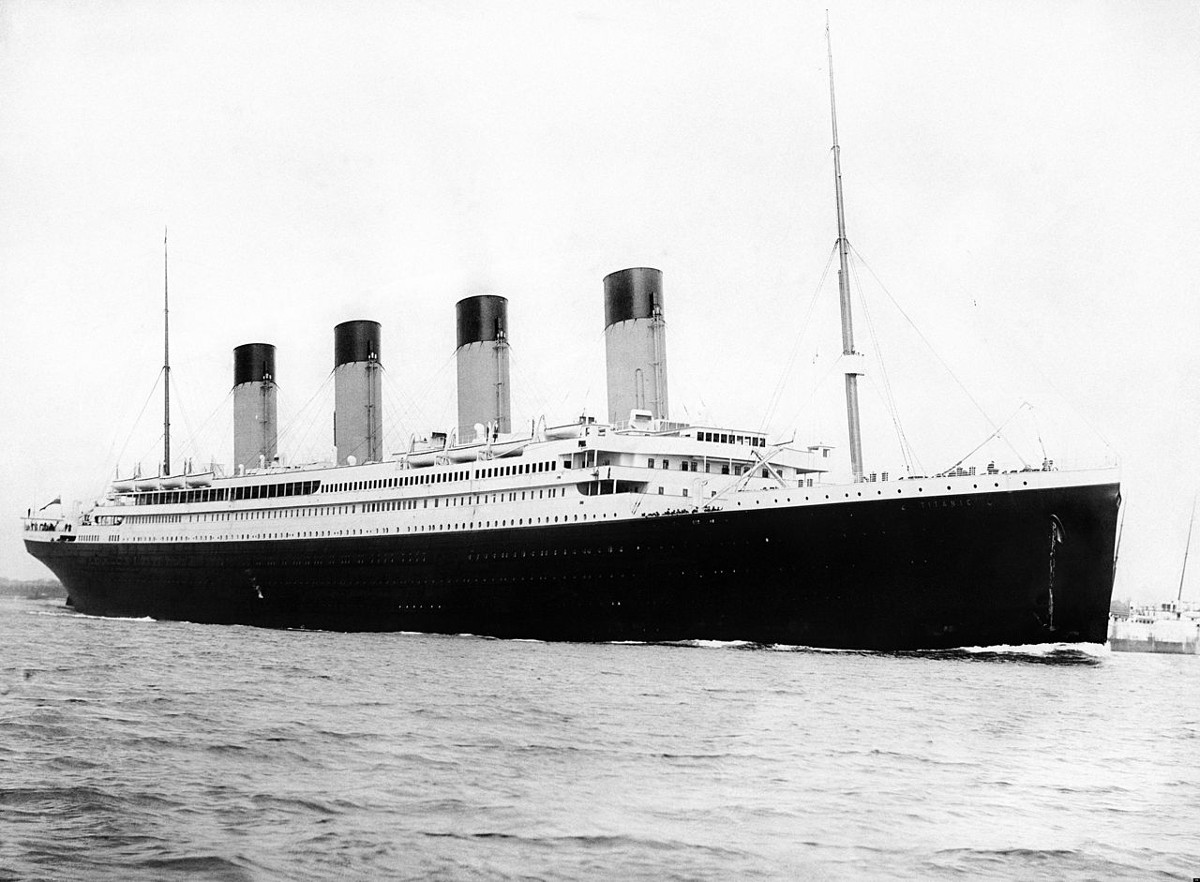

Science teacher Lawrence Beesley was reading a book in his cabin on the Titanic when the engines stopped. Wandering the ship, he heard that an iceberg had passed by but found nothing amiss. But as he was returning to his cabin he noticed something unusual:

As I passed to the door to go down, I looked forward again and saw to my surprise an undoubted tilt downwards from the stern to the bows: only a slight slope, which I don’t think any one had noticed, — at any rate, they had not remarked on it. As I went downstairs a confirmation of this tilting forward came in something unusual about the stairs, a curious sense of something out of balance and of not being able to put one’s feet down in the right place: naturally, being tilted forward, the stairs would slope downwards at an angle and tend to throw one forward. I could not see any visible slope of the stairway: it was perceptible only by the sense of balance at this time.

When the crew began to summon passengers, he returned to A Deck and was accepted on a lifeboat.

(From his 1912 book The Loss of the S.S. Titanic.)

Ground Rules

Articles of the pirate ship Revenge, captain John Phillips, 1723:

- Every man shall obey a civil command. The captain shall have one share and a half of all prizes. The master, carpenter, boatswain and gunner shall have one share and [a] quarter.

- If any man shall offer to run away or keep any secret from the company, he shall be marooned with one bottle of powder, one bottle of water, one small arm and shot.

- If any man shall steal anything in the company or game to the value of a piece-of-eight, he shall be marooned or shot.

- If at any time we should meet another marooner [pirate], that man that shall sign his articles without the consent of our company shall suffer such punishment as the captain and company shall think fit.

- That man that shall strike another whilst these articles are in force shall receive Moses’s Law (that is, forty stripes lacking one) on the bare back.

- That man that shall snap his arms or smoke tobacco in the hold without a cap on his pipe, or carry a candle lighted without a lantern, shall suffer the same punishment as in the former article.

- That man that shall not keep his arms clean, fit for an engagement, or neglect his business, shall be cut off from his share and suffer such other punishment as the captain and the company shall think fit.

- If any man shall lose a joint in time of an engagement, he shall have 400 pieces-of-eight. If a limb, 800.

- If at any time we meet with a prudent woman, that man that offers to meddle with her without her consent, shall suffer present death.

That’s from Charles Johnson’s General History of the Pyrates, 1724. It’s one of only four surviving sets of articles from the golden age of piracy.

Phillips lasted less than eight months as a pirate captain but captured 34 ships in the West Indies.