Author: Greg Ross

“A Very Descript Man”

I am such a dolent man,

I eptly work each day;

My acts are all becilic,

I’ve just ane things to say.

My nerves are strung, my hair is kempt,

I’m gusting and I’m span:

I look with dain on everyone

And am a pudent man.

I travel cognito and make

A delible impression:

I overcome a slight chalance,

With gruntled self-possession.

My dignation would be great

If I should digent be:

I trust my vagance will bring

An astrous life for me.

— J.H. Parker

From Schott’s Vocab. (Thanks, Jacob.)

Podcast Episode 143: The Conscience Fund

For 200 years the U.S. Treasury has maintained a “conscience fund” that accepts repayments from people who have defrauded or stolen from the government. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe the history of the fund and some of the more memorable and puzzling contributions it’s received over the years.

We’ll also ponder Audrey Hepburn’s role in World War II and puzzle over an illness cured by climbing poles.

Crab Computing

In 1982, computer scientists Edward Fredkin and Tommaso Toffoli suggested that it might be possible to construct a computer out of bouncing billiard balls rather than electronic signals. Spherical balls bouncing frictionlessly between buffers and other balls could create circuits that execute logic, at least in principle.

In 2011, Yukio-Pegio Gunji and his colleagues at Kobe University extended this idea in an unexpected direction: They found that “swarms of soldier crabs can implement logical gates when placed in a geometrically constrained environment.” These crabs normally live in lagoons, but at low tide they emerge in swarms that behave in predictable ways. When placed in a corridor and menaced with a shadow representing a crab-eating bird, a swarm will travel forward, and if it encounters another swarm the two will merge and continue in a direction that’s the sum of their respective velocities.

Gunji et al. created a set of corridors that would act as logic gates, first in a simulation and then with groups of 40 real crabs. The OR gate, where two groups of crabs merge, worked well, but the AND gate, which requires the merged swarm to choose one of three paths, was less reliable. Still, the researchers think they can improve this result by making the environment more crab-friendly — which means that someday a working crab-powered computer may be possible.

(Yukio-Pegio Gunji, Yuta Nishiyama, and Andrew Adamatzky, “Robust Soldier Crab Ball Gate,” Complex Systems 20:2 [2011], 93–104.)

The Candy Thief

A problem by Wayne M. Delia and Bernadette D. Barnes:

Five children — Ivan, Sylvia, Ernie, Dennis, and Linda — entered a candy store, and one of them stole a box of candy from the shelf. Afterward each child made three statements:

Ivan:

1. I didn’t take the box of candy.

2. I have never stolen anything.

3. Dennis did it.

Sylvia:

4. I didn’t take the box of candy.

5. I’m rich and I can buy my own candy.

6. Linda knows who the crook is.

Ernie:

7. I didn’t take the box of candy.

8. I didn’t know Linda until this year.

9. Dennis did it.

Dennis:

10. I didn’t take the box of candy.

11. Linda did it.

12. Ivan is lying when he says I stole the candy.

Linda:

13. I didn’t take the box of candy.

14. Sylvia is guilty.

15. Ernie can vouch for me, because he has known me since I was a baby eight years ago.

If each child made two true and one false statement, who stole the candy?

Unquote

G.K. Chesterton admired the furrows in a plowed field, made by patient men who “had no notion of giving great sweeps and swirls to the eye”:

Those cataracts of cloven earth; they were done by the grace of God. I had always rejoiced in them; but I had never found any reason for my joy. There are some very clever people who cannot enjoy the joy unless they understand it. There are other and even cleverer people who say that they lose the joy the moment they do understand it.

(From Alarms and Discursions, 1911.)

Quick Thinking

The historian Socrates tells us that the Emperor Tiberius, who was much given to astrology, used to put the masters of that art, whom he thought of consulting, to a severe test. He took them to the top of his house, and if he saw any reason to suspect their skill, threw them down the steep. Thither he took Thrasyllus, and after a long consultation with him, the emperor suddenly asked whether the astrologer had examined his own fate, and what was portended for him in the immediate future. Now the difficulty is this: If Thrasyllus says that nothing important is about to befall him, he will prove his lack of skill and lose his life besides. If, on the other hand, he says that he is soon to die, either the emperor will set him free, in which case the prophecy was false and he ought to have destroyed him; or Tiberius will destroy him, while he ought to have spared him as a true revealer of the future. Of course the solution is easy. Thrasyllus, after some observations and calculations, began to quake and tremble greatly, and said some great calamity seemed to be impending over him, whereupon the emperor embraced him and made him his chief astrologer.

— The Ladies’ Repository, July 1873

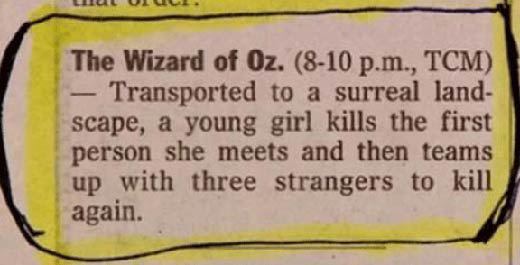

Noted

TV columnist Rick Polito wrote this movie synopsis for the Marin Independent Journal in 1998:

His description of The Untouchables: “A federal agent in Chicago hampers the work of an enterprising American job creator.”

Back Channels

In 1863 Union soldiers seized a bag of rebel correspondence as it was about to cross Lake Pontchartrain. In one of the letters, a woman named Anna boasted of a trick she’d played on a Boston newspaper — she’d sent them a poem titled “The Gypsy’s Wassail,” which she assured them was written in Sanskrit:

Drol setaredefnoc evarb ruo sselb dog

Drageruaeb dna htims nosnhoj eel

Eoj nosnhoj dna htims noskcaj pleh

Ho eixid ni stif meht evig ot

The paper published this “beautiful and patriotic poem, by our talented contributor.” A few days later a reader discovered the trick — it was simply English written in reverse:

God bless our brave Confederates, Lord!

Lee, Johnson, Smith, and Beauregard!

Help Jackson, Smith, and Johnson Joe,

To give them fits in Dixie, oh!

She had signed her name only “Anna,” but in the same bag they found a letter from her sister to her husband, saying “Anna writes you one of her amusing letters,” and this contained her signature and address. Union general Wickham Hoffman wrote to her: “I told her that her letter had fallen into the hands of one of those ‘Yankee’ officers whom she saw fit to abuse, and who was so pleased with its wit that he should take great pleasure in forwarding it to its destination; that in return he had only to ask that when the author of ‘The Gypsy’s Wassail’ favored the expectant world with another poem, he might be honored with an early copy. Anna must have been rather surprised.”

(From Hoffman’s 1877 memoir Camp, Court and Siege.)

Command Performance

Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” played with Glock pistols by Vitaly Kryuchin, president of the Russian Federation of Practical Shooting, from the 1979 Soviet TV miniseries The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed. He also plays “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” and the traditional Russian song “Murka.” It’s probably safest not to make requests.