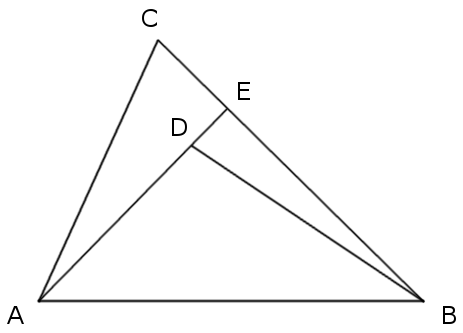

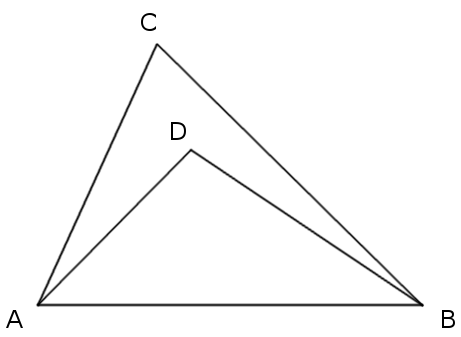

Here’s a triangle, ABC, and an arbitrary point, D, in its interior. How can we prove that AD + DB < AC + CB?

The fact seems obvious, but when the problem is presented on its own, outside of a textbook or some course of study, we have no hint as to what technique to use to prove it. Construct an equation? Apply the Pythagorean theorem?

“The issue is more serious than it first appears,” write Zbigniew Michalewicz and David B. Fogel in How to Solve It (2000). “We have given this very problem to many people, including undergraduate and graduate students, and even full professors in mathematics, engineering, or computer science. Fewer than five percent of them solved this problem within an hour, many of them required several hours, and we witnessed some failures as well.”

Here’s a dismaying hint: Michalewicz and Fogel found the problem in a math text for fifth graders in the United States. What’s the answer?