A foolish young man said to John Wilkes (1725-1797), “Isn’t it strange that I was born on the first of January?”

“Not strange at all,” said Wilkes. “You could only have been conceived on the first of April.”

A foolish young man said to John Wilkes (1725-1797), “Isn’t it strange that I was born on the first of January?”

“Not strange at all,” said Wilkes. “You could only have been conceived on the first of April.”

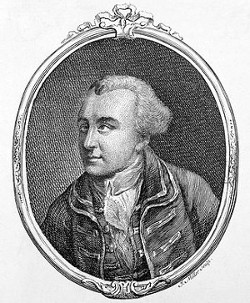

The product of the six numbers surrounding any interior number in Pascal’s triangle is a perfect square.

A leaf was riven from a tree,

“I mean to fall to earth,” said he.

The west wind, rising, made him veer.

“Eastward,” said he, “I now shall steer.”

The east wind rose with greater force.

Said he, “‘Twere wise to change my course.”

With equal power they contend.

He said, “My judgment I suspend.”

Down died the winds; the leaf, elate,

Cried: “I’ve decided to fall straight.”

“First thoughts are best?” That’s not the moral;

Just choose your own and we’ll not quarrel.

Howe’er your choice may chance to fall,

You’ll have no hand in it at all.

— Ambrose Bierce

A puzzle from MIT Technology Review, July/August 2008:

Each of three logicians, A, B, and C, wears a hat that displays a positive integer. The number on one of the hats is the sum of the numbers on the other two. They make the following statements:

A: “I don’t know my number.”

B: “My number is 15.”

What numbers appear on hats A and C?

“There is, on the whole, nothing on earth intended for innocent people so horrible as a school.” — George Bernard Shaw

“I sometimes think it would be better to drown children than to lock them up in present-day schools.” — Marie Curie

“Nearly 12 years of school … form not only the least agreeable, but the only barren and unhappy period of my life. … It was an unending spell of worries that did not then seem petty, of toil uncheered by fruition; a time of discomfort, restriction and purposeless monotony. … I would far rather have been apprenticed as a bricklayer’s mate, or run errands as a messenger boy, or helped my father to dress the front windows of a grocer’s shop. It would have been real; it would have been natural; it would have taught me more; and I should have done it much better.” — Winston Churchill

“Not one of you sitting round this table could run a fish-and-chip shop.” — Howard Florey, 1945 Nobel laureate in medicine, to the governing body of Queen’s College, Oxford, of which he was provost

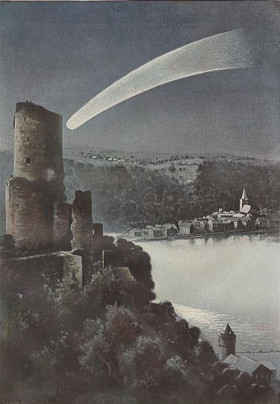

In “The Adventure of the Stockbroker’s Clerk,” Dr. Watson describes Sherlock Holmes as being as pleased as “a connoisseur who has just taken his first sip of a comet vintage.”

That’s a reference to a strange tradition in winemaking: Years in which a comet appears prior to the harvest tend to produce successful vintages:

1826 — Biela’s Comet

1832 — Biela’s Comet

1839 — Biela’s Comet

1845 — Great June Comet of 1845

1846 — Biela’s Comet

1852 — Biela’s Comet

1858 — Comet Donati

1861 — Great Comet of 1861

1874 — Comet Coggia

1985 — Halley’s Comet

1989 — Comet Okazaki-Levy-Rudenko

“For some unexplained reason, or by some strange coincidence, comet years are famous among vine-growers,” noted the New York Times in 1872. “The last comet which was fairly visible to human eyes [and that] remained blazing in the horizon for many months, until it faded slowly away, was seen in 1858, a year dear to all lovers of claret; 1846, 1832 and 1811 were all comet years, and all years of excellent wine.”

No one has even proposed a mechanism to explain how this might be, but it’s widely noted in the wine world: Critic Robert Parker awarded a perfect 100-point rating to the 1811 Château d’Yquem, and cognac makers still put stars on their labels to commemorate that exceptional year.

“Everybody wants to be somebody; nobody wants to grow.” — Goethe

Anna Jarvis organized the first observance of Mother’s Day in 1908 and campaigned to have the holiday adopted throughout the country. But her next four decades were filled with bitterness and acrimony as she watched her “holy day” devolve into a “burdensome, wasteful, expensive gift-day.” In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast, we’ll follow the evolution of Mother’s Day and Jarvis’ belligerent efforts to control it.

We’ll also meet a dog that flummoxed the Nazis and puzzle over why a man is fired for doing his job too well.

The Domestic Names Committee of the U.S. Board on Geographic Names has granted only five possessive apostrophes in 113 years:

Other place names, including Harpers Ferry and Pikes Peak, are generally stripped of their apostrophes in official federal usage (there are some administrative exceptions, such as Prince George’s County, Md.).

The committee argues that an apostrophe implies private ownership of a public place. The United States is the only country with such a policy, but the rule has been reaffirmed five times. In 2013 Jennifer Runyon of the names committee told the Wall Street Journal, “We don’t debate the apostrophe.”

(Thanks, Dave.)

05/24/2017 UPDATE: Apparently New South Wales has a similar rule. From the NSW Addressing User Manual (PDF):

6.7.2.e. An apostrophe mark shall not be included in road names written with a final ‘s’, and the possessive ‘s shall not be included e.g. St Georges Terrace not St George’s Terrace. Apostrophes forming part of an eponymous name shall be included (e.g. O’Connor Road).

(Thanks, Daniel.)

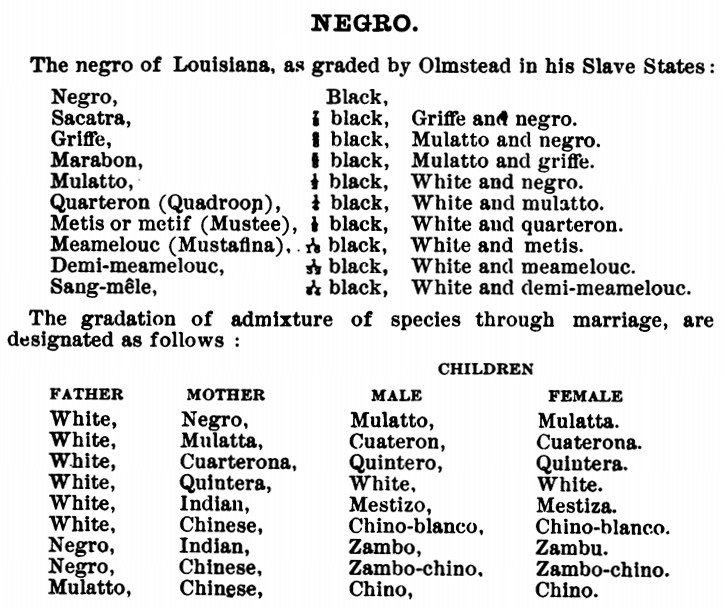

Malcolm Townsend’s U.S.: An Index to the United States of America (1890) contains this table of absurd racial hair-splitting from 1850s Louisiana:

The source is Frederick Law Olmsted’s A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, from 1856.

Olmsted wrote, “All these varieties exist in New Orleans with sub-varieties, and experts pretend to be able to distinguish them.”