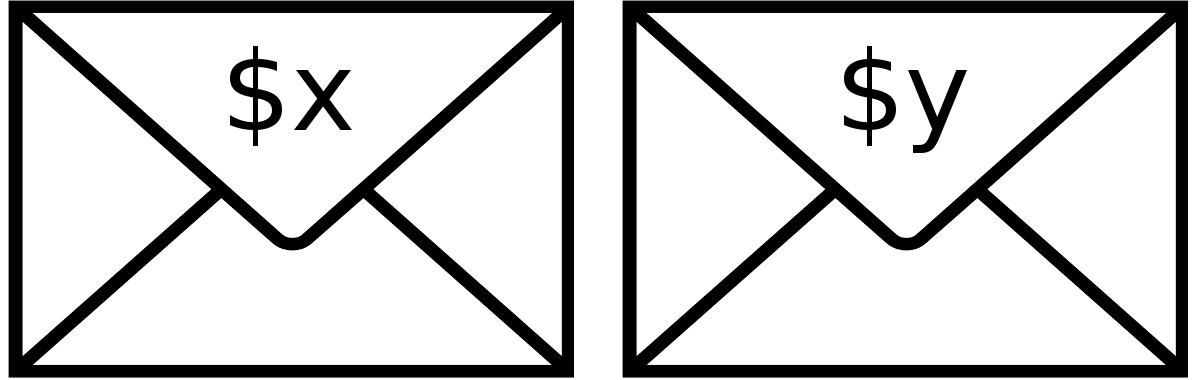

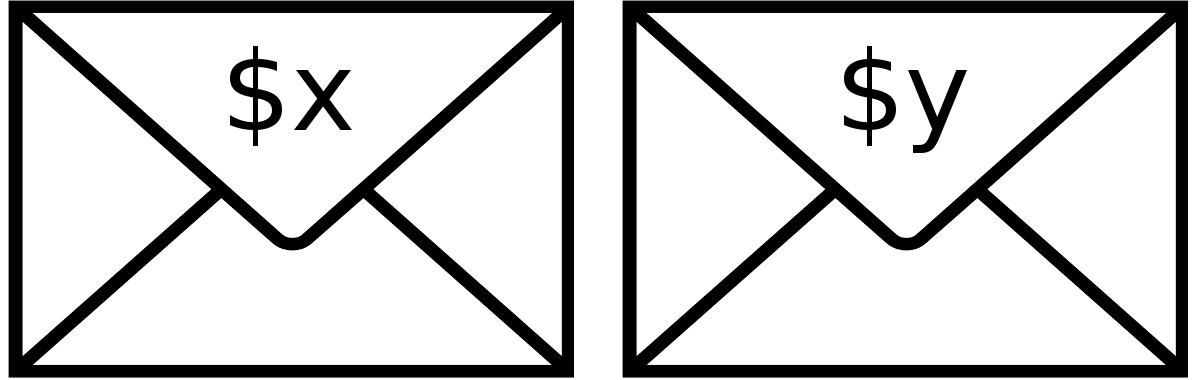

Two envelopes contain unequal sums of money (for simplicity, assume the two amounts are positive integers). The probability distributions are unknown. You choose an envelope at random, open it, and see that it contains x dollars. Now you must predict whether the total in the other envelope is more or less than x.

Since we know nothing about the other envelope, it would seem we have a 50 percent chance of guessing correctly. But, El Camino College mathematician Leonard Wapner writes, “Unexpectedly, there is something you can do, short of opening the other envelope, to give yourself a better than even chance of getting it right.”

Choose a random positive integer, d, by any means at all. (If d = x then choose again until this isn’t the case.) Now if d > x, guess more, and if d < x, guess less. You’ll guess correctly more than 50 percent of the time.

How is this possible? The random number is chosen independently of the envelopes. How can it point in the direction of the unknown y most of the time? “Think of it this way,” writes Wapner. “If d falls between x and y then your prediction (as indicated by d) is guaranteed to be correct. Assume this occurs with probability p. If d falls less than both x and y, then your prediction will be correct only in the event your chosen number x is the larger of the two. There is a 50 percent chance of this. Similarly, if d is greater than both numbers, your prediction will be correct only if your chosen number is the smaller of the two. This occurs with a 50 percent probability as well.”

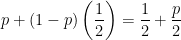

So, on balance, your overall probability of being correct is

That’s greater than 0.5, so the odds are in favor of your making a correct prediction.

This example is based on a principle identified by Stanford statistician David Blackwell. “It’s unexpected and ironic that an unrelated random variable can be used to predict that which appears to be completely unpredictable.”

(Leonard M. Wapner, Unexpected Expectations: The Curiosities of a Mathematical Crystal Ball, 2012, following David Blackwell, “On the Translation Parameter Problem for Discrete Variables,” Annals of Mathematical Statistics 22:3 [1951], 393–399.)