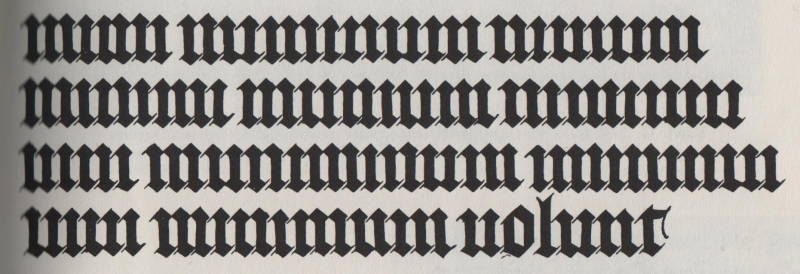

In the 1850s, lovers often corresponded by printing coded messages in the Times. An example from February 1853:

CENERENTOLA. N bnxm yt ywd nk dtz hfs wjfi ymnx fsi fr rtxy fschtzx yt. Mjfw ymf esi, bmjs dtz wjyzws fei mtb qtsldtz wjrfns, ncjwj. lt bwnyf f kjb qnsjx jfuqnsl uqjfxy. N mfaj xnsbj dtz bjsy fbfd.

(“I wish to try if you can read this and am most anxious to hear that and when you return and how long you remain here. Go write a few lines explaining please. I have since you went away.”)

A second message appeared nine days later using the same cipher:

CENERENTOLA. Zsyng rd n jtwy nx xnhp mfaj n y wnj, yt kwfrj fs jcugfifynts ktw dtz lgzy hfssty. Xnqjshj nx nf jny nk ymf ywzj bfzxy nx sty xzx jhyji; nk ny nx, fgg xytwpjx bngg gj xnkyji yt ymjgtyytr. It dtz wjrjgjw tzw htzxns’x knwxy nwtutxnynts: ymnsp tk ny. N pstb Dtz.

(“Until my heart is sick I have tried to frame an explanation for you but cannot. Silence is safest if the true cause is not suspected; if it is, all stories will be sifted to the bottom. Do remember our cousin’s first proposition. Think of it. I know you.”)

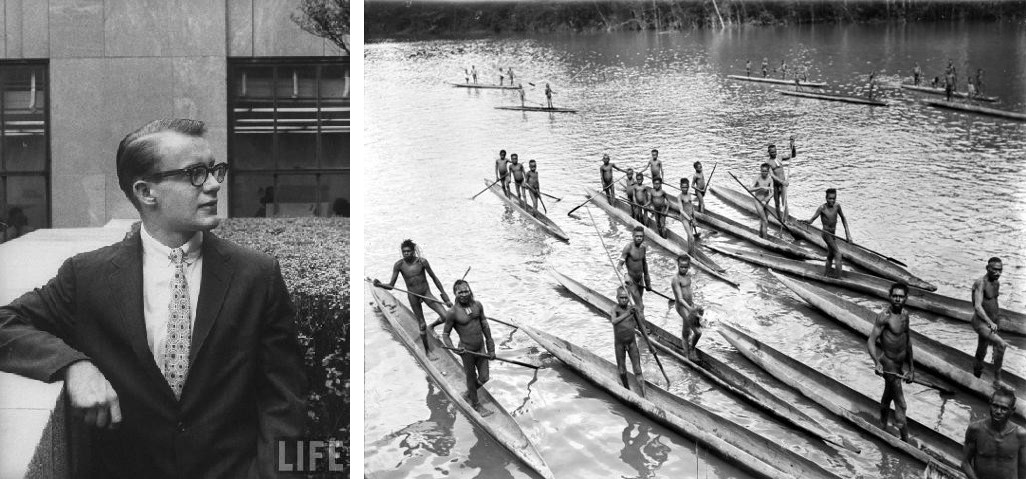

This practice was so well known that cracking the codes became a regular recreation among certain Londoners. Lyon Playfair and Charles Wheatstone uncovered a pending elopement and wrote a remonstrating response to the young woman; she published a new message saying, “Dear Charles, write me no more, our cipher is discovered.”

Most of the messages were simple substitution ciphers, which made them fairly easy to solve, though the lovers seemed to find them challenging — one wrote, “If an honours degree at Oxford cannot read my message, we had better change the cipher. Suggest we revert to numbers. Love, Gwendoline.” But when Playfair and Wheatstone came up with a more secure “symmetrical cipher” and offered it to the Foreign Office, the under-secretary rejected it as “too complicated.”

“We proposed that he should send for four boys from the nearest elementary school,” Playfair wrote, “in order to prove that three of them could be taught to use the cipher in a quarter of an hour. The reply to this proposal by their Under-Secretary was … ‘That is very possible, but you could never teach it to attachés.'”

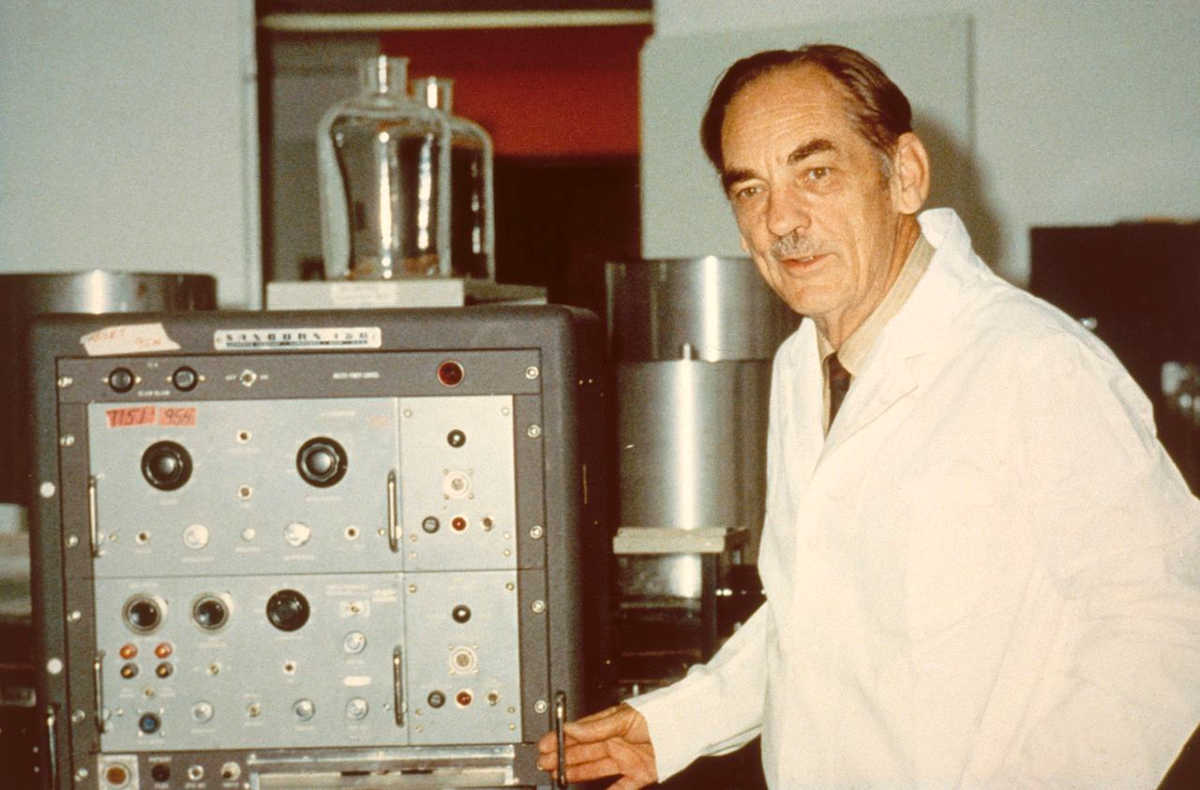

(From Donald McCormick, Love in Code, 1980. Here’s a whole book of messages, both coded and clear.)