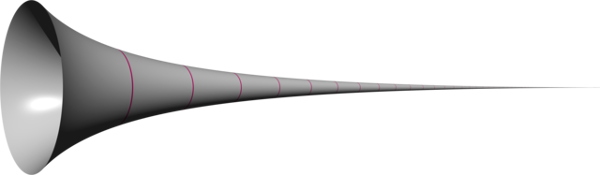

In the 17th century, Italian mathematician Evangelista Torricelli experimented with a figure known as Gabriel’s Horn. Rotate the function y = 1/x about the x-axis for x ≥ 1. The resulting figure has finite volume but infinite surface area — it’s sometimes said that, while the horn could be filled up with π cubic units of paint, an infinite number of square units of paint would be needed to cover its surface.

English cosmologist John D. Barrow describes an infinite wedding cake in which each tier is a solid cylinder 1 unit high; the bottom tier has radius 1, the second radius 1/2, the third radius 1/3, and so on. Now the total volume of the cake is π3/6, but the area of its surface is infinite. Barrow writes, “Our infinite cake recipe requires a finite volume of cake to make but it can never be iced because it has an infinite surface area!”

Mike Steuben, a correspondent of Martin Gardner, imagined a set of boxes, each with area 1 × 1. If the height of the first box is 1, the second 1/2, the third 1/4, and so on, then the total volume of the group is 2 cubic units, but the length and the total area of the tops are infinite.

(Barrow’s example is from 100 Essential Things You Didn’t Know You Didn’t Know About Math and the Arts, 2014.)