hallucar

adj. pertaining to the big toe

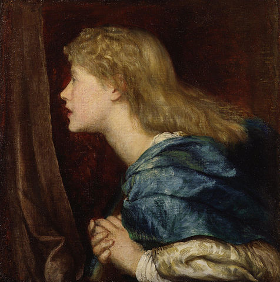

In 1856, 10-year-old Ellen Terry was just about to give Puck’s final speech in A Midsummer Night’s Dream when a stagehand closed a trapdoor on her foot, breaking her toe. She screamed, but manager Ellen Kean offered to double her salary if she finished the play. So, supported by Kean on one side and her sister Kate on the other, she delivered the following soliloquy:

If we shadows have offended (Oh, Katie, Katie!)

Think but this, and all is mended, (Oh, my toe!)

That you have but slumbered here,

While these visions did appear. (I can’t, I can’t!)

And this weak and idle theme,

No more yielding but a dream, (Oh, dear! oh, dear!)

Gentles, do not reprehend; (A big sob)

If you pardon, we will mend. (Oh, Mrs. Kean!)

“How I got through it, I don’t know!” she wrote in her 1908 memoir. “But my salary was doubled — it had been fifteen shillings, and it was raised to thirty — and Mr. Skey, President of Bartholomew’s Hospital, who chanced to be in a stall that very evening, came round behind the scenes and put my toe right. He remained my friend for life.”