Back in September I posted a geometry problem mentioned by Andy Liu in Math Horizons in November 1997. Several readers recognized it and wrote in with the pretty solution — here it is:

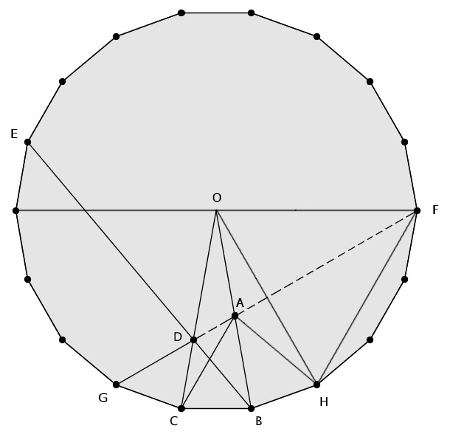

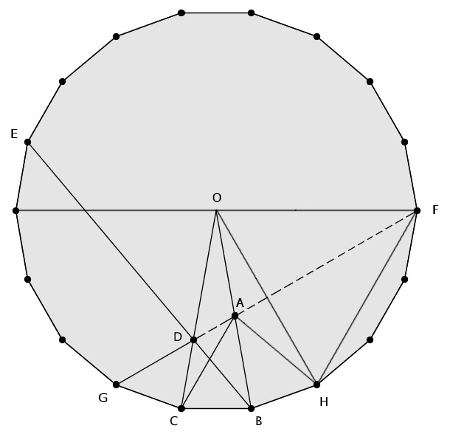

As before, we’re given that ∠DCA = 20°, ∠ACB = 60°, ∠CBD = 50°, and ∠DBA = 30°, and we’re asked to find ∠CAD. Start by extending CD and BA to intersect at O, and draw a circle with O as the center and OB as the radius. Now, because ∠OCB and ∠OBC both measure 80°, BC is one side of an 18-gon inscribed in this circle.

Let E be the fifth vertex of this 18-gon to the left of C and F be the fifth vertex to the right of C. Also let G be the first vertex to the left of C and H be the first vertex to the right of B. Then, by symmetry, EB, GF, and OC meet. And by the central angle theorem ∠EBC is half the measure of ∠EOC, or 50°, so EB, GF, and OC meet at D.

Now, OFH is an equilateral triangle (by symmetry and the fact that ∠FOH is 60°), and ∠GFH is half the measure of ∠GOH, or 30° (again by the central angle theorem). So GF bisects OH.

Finally, by symmetry, AC = AH. But ∠ACD = 20° = ∠AOD, so triangle AOC is equilateral and AC = AO. Then AO = AH, and by symmetry AF bisects OH. And that means that GF passes through A.

Therefore, ∠BAD = ∠OAF, which is half of ∠OAH, or 70°. And from the information given at the start we can infer that ∠CAB = 40°. So ∠CAD = 30°.

I’m told that there are more problems like this in I.F. Sharygin’s 1988 book Problems in Plane Geometry. Thanks to the folks who wrote in about this.

11/06/2015 UPDATE: Another reader pointed out an alternate solution, discovered by Edward Mann Langley in 1922. (Thanks, January.)