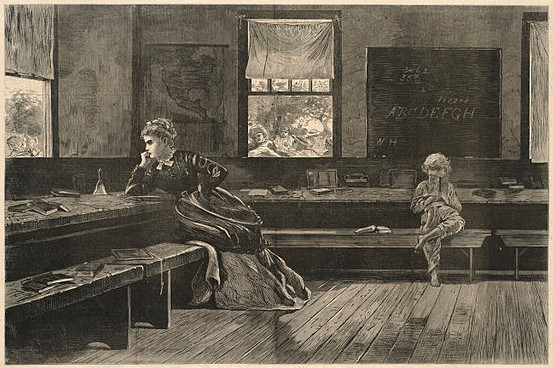

On Oct. 25, 1875, Lewis Carroll sent this verse to Mrs. J. Chataway, mother of one of his child-friends, Gertrude. “They embody, as you will see, some of my recollections of pleasant days at Sandown”:

Girt with a boyish garb for boyish task,

Eager she wields her spade — yet loves as well

Rest on a friendly knee, the tale to ask

That he delights to tell.

Rude spirits of the seething outer strife,

Unmeet to read her pure and simple spright,

Deem, if you list, such hours a waste of life,

Empty of all delight!

Chat on, sweet maid, and rescue from annoy

Hearts that by wiser talk are unbeguiled!

Ah, happy he who owns that tenderest joy,

The heart-love of a child!

Away, fond thoughts, and vex my soul no more!

Work claims my wakeful nights, my busy days:

Albeit bright memories of that sunlit shore

Yet haunt my dreaming gaze!

He asked her leave to have it published. The child in the verse is not named — why should he feel obliged to ask permission?