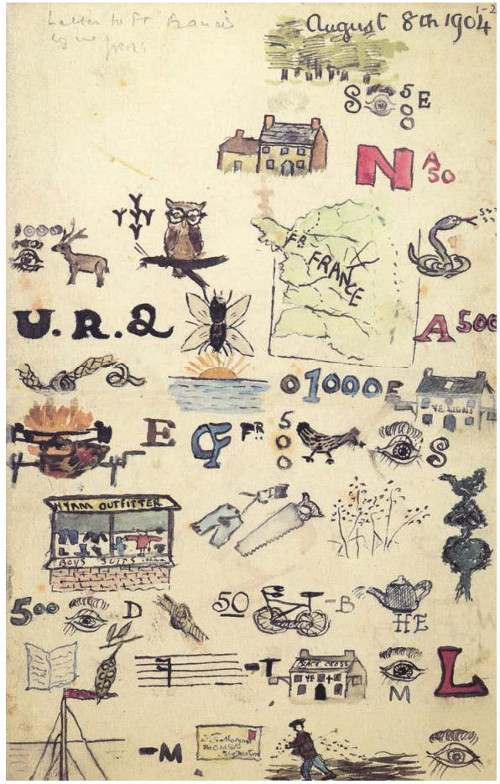

From a letter by Lewis Carroll, about 1848:

I have not yet been able to get the second volume Macaulay’s ‘England’ to read. I have seen it however and one passage struck me when seven bishops had signed the invitation to the pretender, and King James sent for Bishop Compton (who was one of the seven) and asked him ‘whether he or any of his ecclesiastical brethren had anything to do with it?’ He replied, after a moment’s thought ‘I am fully persuaded your majesty, that there is not one of my brethren who is not as innocent in the matter as myself.’

“This was certainly no actual lie,” Carroll wrote, “but certainly, as Macaulay says, it was very little different from one.”