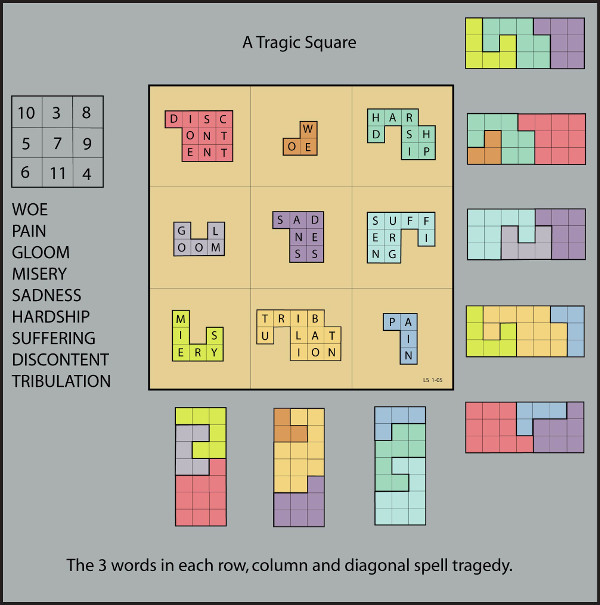

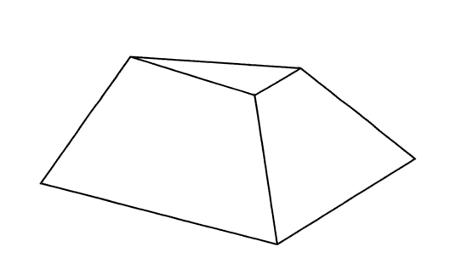

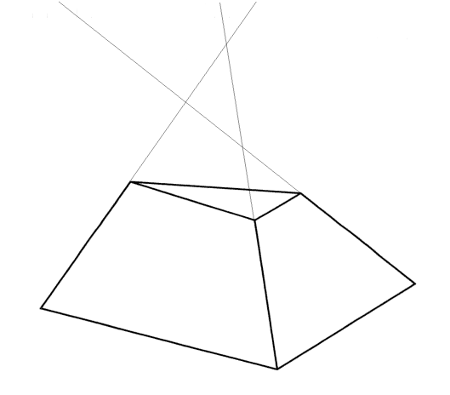

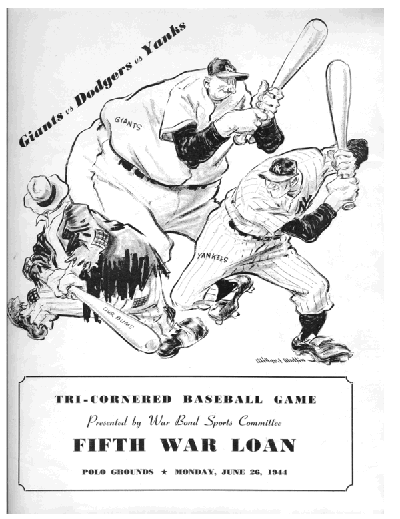

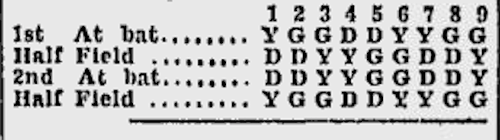

In 1944, eager to help the war effort, a group of New York sportswriters arranged a three-way baseball game among the Brooklyn Dodgers, the New York Yankees, and the New York Giants. The teams took turns batting, fielding, and sitting so that each played a total of six innings, under a scheme concocted by Columbia University math professor Paul A. Smith:

Leo Durocher managed the Dodgers, Joe McCarthy the Yankees, and Mel Ott the Giants. The Dodgers showed a strange talent for this sort of play, winning 5-1-0 and shutting out the Giants entirely. The game “drew a gathering of 50,000, which included 500 wounded service heroes,” reported the New York Times, whose Byzantine box score is reproduced here.

“It helped swell New York’s war bond quota by approximately $56,500,000, and it also demonstrated that no matter how much you may strive to complicate things, the Dodgers, who still insist on doing things in their own fashion, will invariably continue to find their way around.”