On hearing that Watership Down was a novel about rabbits written by a civil servant, Craig Brown wrote, “I would rather read a novel about civil servants written by a rabbit.”

Author: Greg Ross

“Alternative Endings to an Unwritten Ballad”

I stole through the dungeons, while everyone slept,

Till I came to the cage where the Monster was kept.

There, locked in the arms of a Giant Baboon,

Rigid and smiling, lay … Mrs. RAVOON!

I climbed the clock-tower in the first morning sun

And ’twas midday at least ere my journey was done;

But the clock never sounded the last stroke of noon,

For there, from the clapper, swung Mrs. RAVOON.

I ran through the marsh ‘midst the lightning and thunder,

When a terrible flash split the darkness asunder.

Chewing a rat’s tail and mumbling a rune,

Mad in the moat, squatted Mrs. RAVOON.

I stood by the waters so green and so thick,

And I stirred at the scum with my old, withered stick;

When there rose through the ooze, like a monstrous balloon,

The bloated cadaver of Mrs. RAVOON.

I hauled in the line, and I took my first look

At the half-eaten horror that hung from the hook.

I had dragged from the depths of the limpid lagoon

The luminous body of Mrs. RAVOON.

Facing the fens, I looked back from the shore

Where all had been empty a moment before;

And there, by the light of the Lincolnshire moon,

Immense on the marshes, stood … Mrs. RAVOON!

After this memorable debut in For Love and Money (1956), Paul Dehn’s macabre character has found her way into songs and poems by many writers, even beyond her creator’s death in 1976. They’re cataloged here.

No Comment

“Lady Dillon told Sir F. Chantrey that English women were more buxom than Italian women. The delicate way she put it was, ‘you will find that Italian women can sit much closer to a wall than English.'”

— George Lyttelton’s Commonplace Book, 2002

Spectator

A surprising detail from Duke Ellington’s childhood, from his 1973 autobiography Music Is My Mistress:

There were many open lots around Washington then, and we used to play baseball at an old tennis court on Sixteenth Street. President Roosevelt would come by on his horse sometimes, and stop and watch us play. When he got ready to go, he would wave and we would wave at him. That was Teddy Roosevelt — just him and his horse, nobody guarding him.

Many Worlds

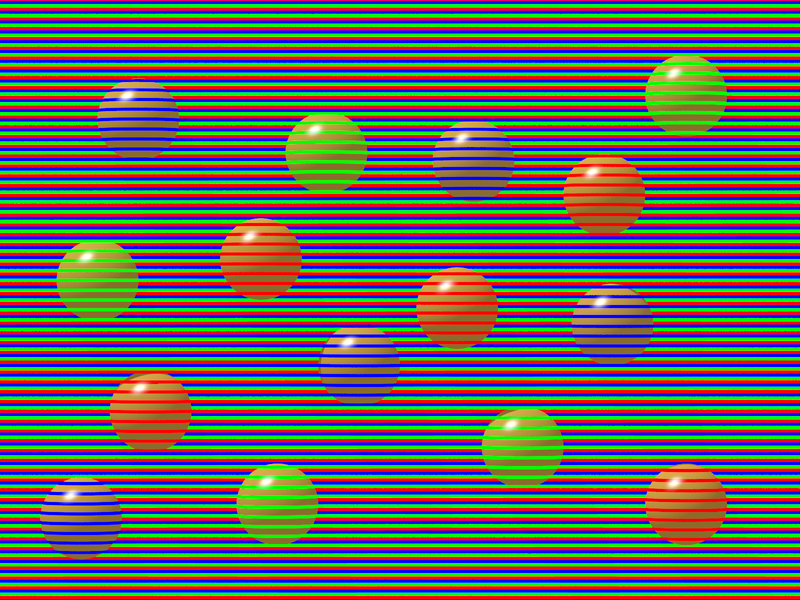

An illusion by University of Texas engineer David Novick: All the spheres have the same light-brown base color (RGB 255,188,144). The intervening foreground stripes seem to impart different hues. See this Twitter thread for the same image with the foreground stripes removed.

Good Advice

Have the love and fear of God ever before thine eyes; God confirm your faith in Christ and that you may live accordingly, Je vous recommende a Dieu. If you meet with any pretty insects of any kind keep them in a box.

— Sir Thomas Browne, letter to his son, 1661

Missing the Mark

“The Holy Roman Empire was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.” — Voltaire

“It has been said that this Minister [the Lord Privy Seal] is neither a Lord, nor a privy, nor a seal.” — Sydney D. Bailey

“Television is a medium, so called because it is neither rare nor well done.” — Ernie Kovacs

Interloper

After the Battle of Waterloo, the Duke of Wellington was constantly asked to describe his adventures on that day. Eventually he insisted that all his stories had been told, but during a visit to the Marchioness of Downshire, he said, “Well, I’ll tell you one that has not been printed.”

In the middle of the battle of Waterloo he saw a man in plain clothes riding about on a cob in the thickest fire. During a temporary lull the Duke beckoned him, and he rode over. He asked him who he was, and what business he had there. He replied he was an Englishman accidentally at Brussels, that he had never seen a fight and wanted to see one. The Duke told him he was in instant danger of his life; he said ‘Not more than your Grace,’ and they parted.

But every now and then he saw the Cob-man riding about in the smoke, and at last having nobody to send to a regiment, he again beckoned to this little fellow, and told him to go up to that regiment and order them to charge, giving him some mark of authority the colonel would recognise. Away he galloped, and in a few minutes the Duke saw his order obeyed. The Duke asked him for his card, and found in the evening, when the card fell out of his sash, that he lived at Birmingham, and was a button manufacturer!

“When at Birmingham the Duke inquired of the firm and found he was their traveller and then in Ireland. When he returned, at the Duke’s request he called on him in London. The Duke was happy to see him and said he had a vacancy in the Mint of 800l. a-year, where accounts were wanted. The little Cob-man said it would be exactly the thing and the Duke installed him.”

(Attributed to John Edward Carew in The Life of Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1853.)

Passing Tones

If you’re driving on the highway and pass a car traveling in the opposite direction, the frequency of its engine noise seems to drop. In 1980, Liverpool Polytechnic mathematician J.M.H. Peters realized that this pitch drop might be used to estimate the speed of the passing vehicle. Pleasingly, he discovered that each semitone in the interval corresponds to 21 miles per hour (to within 2 percent). If the other car’s engine seems to descend a whole tone in pitch as it passes you, then it’s traveling at approximately 43 mph; if it drops a minor third then it’s traveling at 64 mph; and so on.

“The reader should practise by humming a given note pianissimo increasing gradually to fortissimo at which point the hum is lowered by a chosen interval, … diminishing again to pianissimo, this being meant to imitate the effect of being suddenly passed on a quiet country lane by a fast moving high powered motor vehicle.”

(J.M.H. Peters, “64.8 Estimating the Speed of a Passing Vehicle,” Mathematical Gazette 64:428 [June 1980], 122-124.)

03/03/2025 UPDATE: My mistake — the observer is stationary, not moving. Thanks to readers Seth Cohen and Jon Jerome for pointing this out. The cited paper is behind a paywall, but the Physics Stack Exchange had a discussion on the same topic in 2017.

By the Book

The classic, of course, is the story that tells how Mrs. Webster once accidentally walked into a room and found her husband kissing the maid. ‘Noah!’ she exclaimed, ‘I’m surprised.’ Noah, ever the verbalist, was nonplussed. ‘No, my dear,’ he corrected. ‘It is I who am surprised. You are astonished.’

— Evan Esar, Humorous English, 1961