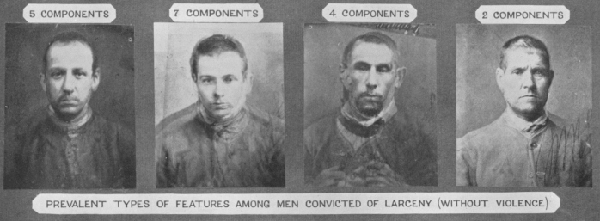

In 1883 Francis Galton tried an experiment: He combined multiple photographs of criminals into composite images, hoping to discover an underlying “type.” He didn’t get a strong result, but he did notice something odd about the composite faces: They tended to be more attractive than the individual images that made them up. He found similar effects with other groups — a composite “sick person” seemed healthier than its constituent images, and a group of good-looking people became even more beautiful in composite. In one case he made a “singularly beautiful combination of the faces of six different Roman ladies, forming a charming ideal profile.”

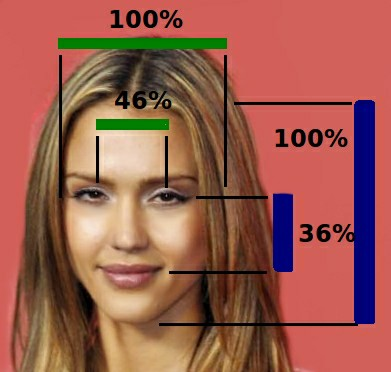

The lesson seems to be that we find an “average” face most attractive — a face is appealing not because it has unusual features but because it lacks them. For example (below), a University of Toronto study found that the shape of Jessica Alba’s face approaches the average for all female profiles: The distance between her pupils is 46 percent of the width of her face, and the distance between her eyes and her mouth is 36 percent of the length of her face. The fact that we find this attractive makes some evolutionary sense: Natural selection tends to drive out disadvantageous features, so a partner with an “average” face is more likely to be healthy and fertile.