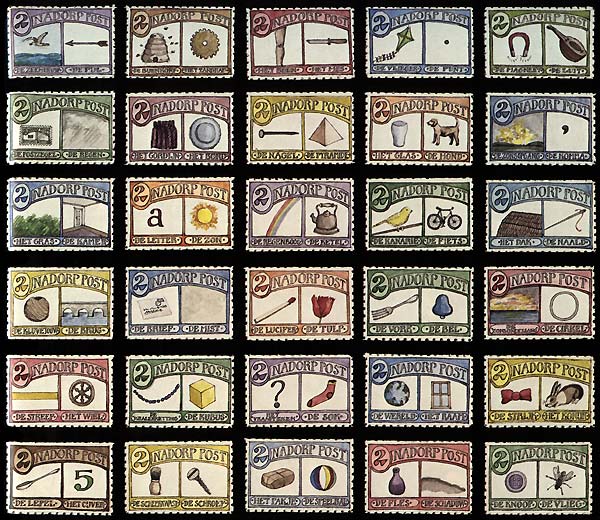

Artist Donald Evans spent his life painting the postage stamps of nonexistent countries. “The stamps are a kind of diary or journal,” he said. “It’s vicarious traveling for me to a made-up world that I like better than the one that I’m in.”

“On little paper rectangles he painted precise transcriptions of his life,” wrote Willy Eisenhart in The World of Donald Evans (1980). “He commemorated everything that was special to him, disguised in a code of stamps from his own imaginary countries — each detailed with its own history, geography, climate, currency and customs — all of it representative of the real world but, like real stamps, apart from it in calm tranquility.”

He painted them as watercolors the size of actual stamps, handling the paper with tweezers and working always with the same trusty brush. When they were finished he would sometimes cancel them with a fanciful postmark carved from a rubber eraser. He preserved them in a 330-page book modeled on a real stamp catalogue, recording in each case the name of the fictional country, the fictional date, the subject and occasion of the stamp’s issue, and the date on which he had completed the painting. He called this book his Catalogue of the World.

By the time he died in an Amsterdam fire in 1977, Evans had painted nearly 4,000 stamps from 42 imaginary nations, bearing dates from 1852 to 1973. He told the Paris Review, “The more I do, the more crazy and minuscule the detail becomes and the more stamplike they become. And that intrigues me. … One of the things I get excited about in making this work is that I try to make it look real.”

The guiding principle for his work, he said, was “basically that it describes something which I think is interesting and that it looks like a stamp.”