brumal

adj. wintry

hibernal

adj. of, pertaining to, or proper to winter

hiemal

adj. of or belonging to winter

brumal

adj. wintry

hibernal

adj. of, pertaining to, or proper to winter

hiemal

adj. of or belonging to winter

“People who make history know nothing about history. You can see that in the sort of history they make.” — G.K. Chesterton

In 1892 Frederic Martyn was fighting in West Africa with the French Foreign Legion when he met with an incident “so remarkable that I hesitate to mention it, as it is pretty certain to be regarded as a mere traveller’s tale”:

A Dahomeyan warrior was killed while in the act of levelling his gun, from behind a cotton tree, at Captain Battreau of the Legion, at point-blank range, and as he fell his rifle clattered down at the officer’s feet. Captain Battreau, seeing that it was an old Chassepot, picked it up out of curiosity, and suddenly became very much interested in it. He examined it very carefully, and then exclaimed, with a gasp of astonishment, ‘Well, this is something like a miracle! Here is the very rifle I used in 1870 during the war with Germany! See that hole in the butt? That was made by a Prussian bullet at Saint-Privat. I could tell that gun from among a million by that mark alone; but here’s my number stamped on it as well, which is evidence enough for anybody. Who would have thought it possible that I could pick up in Africa, as a captain, a rifle that I used in France, as a sergeant, twenty-two years ago? It is incredible!’

Martyn writes, “The sceptical reader will probably think that the captain was ‘pulling our legs’ a bit; but this explanation is inconsistent with the fact that the officer asked for and obtained special permission to keep the rifle as personal property on account of its associations, and he was hardly likely to have done this unless he could prove that it was, in fact, the identical rifle he had formerly used.”

(From Martyn’s 1911 memoir Life in the Legion. Thanks, Kevin.)

On June 30, 1960, a thunderstorm struck the Columbia, Missouri, area and made time not only stand still, but go backward. The Columbia Missourian reported that Mr. C.W. Brenton looked at his electrical clock at 7:55 P.M. and was startled to see that the clock was running backward. During the storm a surge of lightning had entered his home along the power lines and fused some of the wiring in the clock. This apparently reversed the magnetic field of the motor, causing the hands to turn in the wrong direction.

— Peter Viemeister, The Lightning Book, 1961

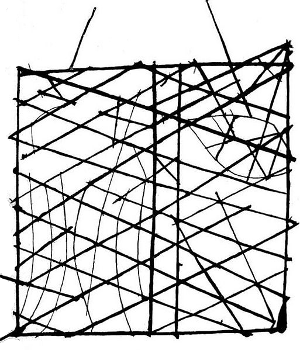

What is this? It’s a map. In order to navigate by canoe among the Marshall Islands, residents made charts by lashing together sticks, threads, and shells to represent landmasses and the patterns of ocean swells and breakers between them.

The atolls lie so low that even the tops of the palms are lost to sight 20 kilometers off shore, so a Marshallese navigator may spend several days out of sight of land. Having studied swell patterns with the aid of such charts, he can find his way by observing the motion of his canoe.

For example, an island breaks up the easterly trade wind swell, producing a wave pattern that signals the presence of land. “These navigation signs … extend seaward from any atoll or island in specific quadrants and can be detected up to 40 km away,” writes oceanographer Joseph Genz. “The relative strength of these radiating wave patterns indicates the distance toward land, while the specific wave signatures indicate the direction of land.”

(Joseph Genz et al., “Wave Navigation in the Marshall Islands,” Oceanography, June 2009.)

To pay for 1 frognab you’ll need at least four standard U.S. coins. To pay for 2, you’ll need at least six coins. But you can buy three with two coins. How much is 1 frognab?

In a standard 10-frame game of bowling, the lowest possible score is 0 (all gutterballs) and the highest is 300 (all strikes). An average player falls somewhere between these extremes. In 1985, Central Missouri State University mathematicians Curtis Cooper and Robert Kennedy wondered what the game’s theoretical average score is — if you compiled the score sheets for every legally possible game of bowling, what would be the arithmetic mean of the scores?

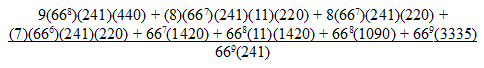

It turns out it’s pretty low. There are (669)(241) possible games, which is about 5.7 × 1018. If we divide that into the total number of points scored in these games, we get

which is about 80 (79.7439 …).

This “might make you feel better about your average,” Cooper and Kennedy conclude. “The mean bowling score is indeed awful even if you are just an occasional bowler. Even though this information is interesting, there are more difficult questions about the game of bowling that could be asked. For example, you might wish to determine the standard deviation of the set of bowling scores and hence know more about the distribution of the set of all bowling scores. But the exact determination of the distibution of the set of scores is, in our opinion, a difficult problem. For example, given an integer k between 0 and 300, how many different bowling games have the score k? This, we leave as an open problem.”

(Curtis N. Cooper and Robert E. Kennedy, “Is the Mean Bowling Score Awful?”, Journal of Recreational Mathematics 18:3, 1985-86.)

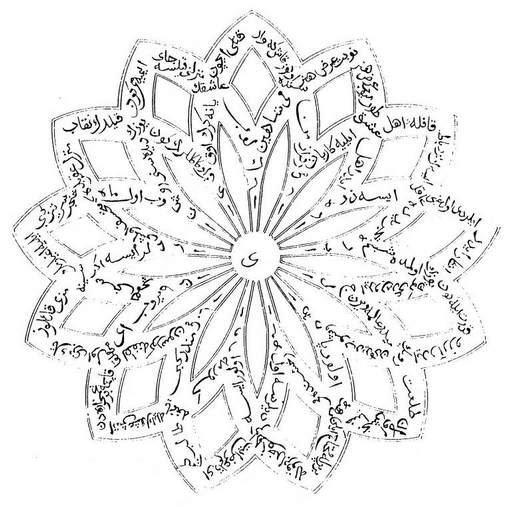

This love lyric was written by Shahin Ghiray (c. 1747-1787), the last sultan of the independent Crimea before its conquest by the Russians. It’s written in Turkish but in the Persian letter style of Arabic. The reader starts at the central letter and reads upward, which leads him into a series of arcs around the circle. Each arc forms a diptych that begins and ends with the central letter, and each line in the diptych intersects its neighbor so that they share a word.

Poet Dick Higgins writes, “When I asked a Persian student to read this for me, the sound, with its opening alliterations, was as much a tour de force as the visual aspect.” Unfortunately it’s hard to reflect all this in English; J.W. Redhouse attempted this translation in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1861:

Let but my beloved come and take up her abode in the mansion of her lover, and shall not thy beautiful face cause his eyes to sparkle with delight!

Or, would she but attack my rival with her glances, sharp-pointed as daggers, and, piercing his breast, cause him to moan, as a flute is pierced ere it emit its sighing notes.

Turn not away, my beauty; nor flee from me, who am a prey to grief; deem it not fitting that I be consumed with the fire of my love for thee.

If the grace of God favour one of His servants, that man, from a state of utter destitution, may become the monarch of the world.

Tears flow from my eyes by reason of their desire to reach thee; for the sun of thy countenance, by an ordinance of the Almighty power, attracts to itself the moisture of the dew-drops.

If thou art wise, erect an inn on the road of self-negation; so that the pilgrims of holy love may make thereof their halting-place.

O proud and noble mistress of mine! with the eyebrows and glances that thou possessest, what need of bow or arrow wherewith to slay thy lover?

Is it that thou hast loosed thy tresses and veiled therewith the sun of thy countenance? Or is it that the moon has become eclipsed in the sign of Scorpio?

I am perfectly willing that my beloved should pierce my heart; only let that beauty deem me worthy of her favour.

Write, O pen! that I am a candidate for the flames, even as a salamander; declare it to be so, if that queen of beauty will it.

Is it the silvery lustre of the moon that has diffused brightness over the face of nature; or is it the sun of thy countenance that has illumined the world?

If any disputant should cavil, and deny the existence of thy beauty, would not thy adorer, hovering as a mote in its rays, suffice to convince the fool, if he had but common sense?

It is true that lovers do unremittingly dedicate their talents to the praise of their mistresses; but has thy turn yet come, Shahin-Ghiray, so to offer thy tribute of laudation?

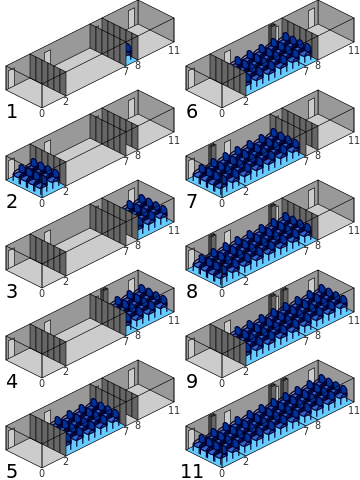

This conference room is 11 units long and has folding partitions at positions 2, 7, and 8. This gives it a curious property: For a meeting of any given size, the room can be configured in exactly one way. A meeting of size 6 must use partitions 2 and 8 — no other setup will work exactly.

This is an example of a Golomb ruler, named for USC mathematician Solomon Golomb. It’s called a ruler because the simplest example is a measuring stick: If we’re given a 6-centimeter ruler, we find that we can add 4 marks (at integer positions) so that no two of them are the same distance apart: 0 1 4 6. No shorter ruler can accommodate 4 marks without duplication, so the 0-1-4-6 ruler is said to be “optimal.” It’s also “perfect” because it can measure any distance from 1 to 6.

The conference room is optimal because no shorter room can accommodate 5 walls without equal-sized partitions becoming available, but it’s not perfect, because it can’t accommodate an assembly of size 10. (It turns out that no perfect ruler with five marks is possible.)

Finding optimal Golomb rulers is hard — simply extending an existing ruler tends to produce a new ruler that’s either not Golomb or not optimal. The only way forward, it seems, is to compare every possible ruler with n marks and note the shortest one, an immensely laborious process. Distributed computing projects have found the longest optimal rulers to date — the most recent, with 27 marks, was found in February, five years after the previous record.