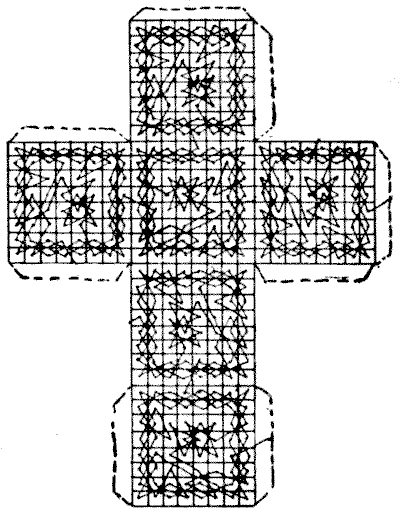

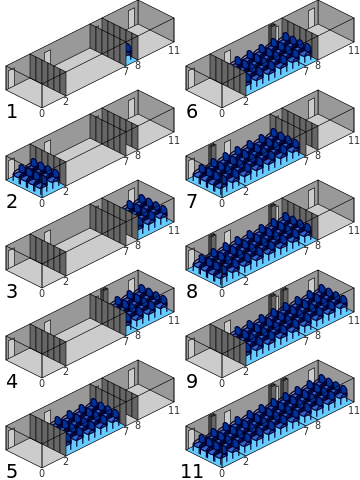

This conference room is 11 units long and has folding partitions at positions 2, 7, and 8. This gives it a curious property: For a meeting of any given size, the room can be configured in exactly one way. A meeting of size 6 must use partitions 2 and 8 — no other setup will work exactly.

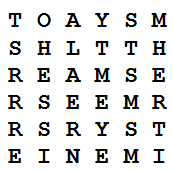

This is an example of a Golomb ruler, named for USC mathematician Solomon Golomb. It’s called a ruler because the simplest example is a measuring stick: If we’re given a 6-centimeter ruler, we find that we can add 4 marks (at integer positions) so that no two of them are the same distance apart: 0 1 4 6. No shorter ruler can accommodate 4 marks without duplication, so the 0-1-4-6 ruler is said to be “optimal.” It’s also “perfect” because it can measure any distance from 1 to 6.

The conference room is optimal because no shorter room can accommodate 5 walls without equal-sized partitions becoming available, but it’s not perfect, because it can’t accommodate an assembly of size 10. (It turns out that no perfect ruler with five marks is possible.)

Finding optimal Golomb rulers is hard — simply extending an existing ruler tends to produce a new ruler that’s either not Golomb or not optimal. The only way forward, it seems, is to compare every possible ruler with n marks and note the shortest one, an immensely laborious process. Distributed computing projects have found the longest optimal rulers to date — the most recent, with 27 marks, was found in February, five years after the previous record.