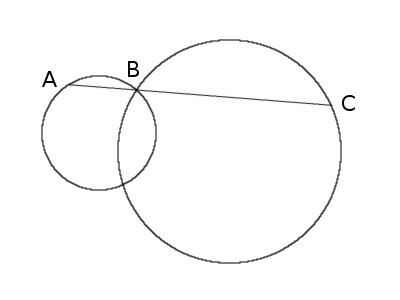

Two circles intersect. A line AC is drawn through one of the intersection points, B. AC can pivot around point B — what position will maximize its length?

Two circles intersect. A line AC is drawn through one of the intersection points, B. AC can pivot around point B — what position will maximize its length?

consenescence

n. the growing old together

Midway along the northwestern face of a monumental Inca building at 410 Calle Hatunrumiyoc in Cusco is a large irregular block of stone worked by a master mason in the era before Columbus. Fitted into place without mortar despite its complex shape, the “twelve-angled stone” has become a hallmark of Inca craftsmanship.

“Just as individual blocks were prepared, so too were the adjoining stones already set in the wall,” notes Southern Methodist University art historian Adam Herring. “In order to receive a new block, bedding planes were carved into those stones below or to the side of the block to be added. This is how the Twelve-Angled Stone took on its busy upper outline; the upper portions of the block were recarved several times over as five blocks — set in a left to right sequence — were fitted along the course above. Other blocks in the wall were similarly shaped, then reshaped as new blocks were added to the masonry mass. As stones of irregular size and degree of finish were inserted into the mural fabric with fastidious technical consistency, the wall went up as tectonic sculpture.”

Pablo Neruda remarked on the “rocky petals” that distinguish this style of architecture; Che Guevara called it “an enigma in stone.” The mason who left this hallmark was a master of this craft, but his identity is unknown.

(Adam Herring, “Shimmering Foundation: The Twelve-Angled Stone of Inca Cusco,” Critical Inquiry, Autumn 2010.)

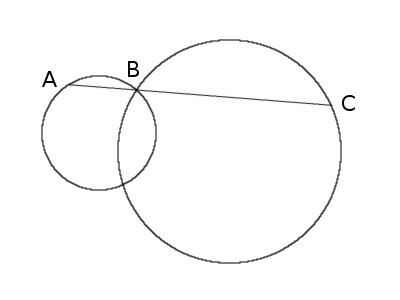

Italian artist Giovanni Piranesi spent his days making etchings of Roman ruins, but in 1745 he turned out a series of much darker visions, which he called Le Carceri d’Invenzione. “Vaults of colossal proportions from which hang extinguished lanterns, openings closed by bars, spiral staircases and suspended passageways which lead nowhere, immense gallows and wheels, ropes strung on pulleys evoking strange tortures,” writes Roseline Bacou in her collection of the artist’s etchings and drawings, “all these are the visible elements of a closed and nocturnal world.” Thomas De Quincey wrote:

Many years ago, when I was looking over Piranesi’s Antiquities of Rome, Mr. Coleridge, who was standing by, described to me a set of plates by that artist … which record the scenery of his own visions during the delirium of a fever: some of them … representing vast Gothic halls, on the floor of which stood all sorts of engines and machinery, wheels, cables, pulleys, levers, catapults, etc., etc., expressive of enormous power put forth, and resistance overcome. Creeping along the sides of the walls, you perceived a staircase; and upon it, groping his way upwards, was Piranesi himself: follow the stairs a little further, and you perceive it come to a sudden abrupt termination, without any balustrade, and allowing no step onwards to him.

The full collection is here. Aldous Huxley read into the prints “things existing in the physical and metaphysical depths of human souls — to acedia and confusion, to nightmare angst, to incomprehension and to panic bewilderment.” In reworking the prints Piranesi came to relate them to early Rome: One column in the vaults bears the inscription AD TERROREM INCRESCENTIS AVDACIAE, a quotation from Livy’s History of Rome in which the early king Ancus Marcius responds to a loss of values among his people by establishing a prison in the center of the city, “to terrify the growing audacity.” But the initial series were pure fantasy, and their inspiration is unknown.

In 1870, John Chippendall Montesquieu Bellew offered a sort of lip-synched Hamlet, in which he read the text at the front of the stage while performers dressed in character acted it out in dumbshow. “The dummies, with the exception of Hamlet, acted but indifferently,” wrote one reviewer. “The gentleman who doubled the characters of Polonius and the First Gravedigger disdained to open his mouth at all, whilst the representative of the King was evidently under the impression that his lips were in the region of his eyebrows, as he moved the latter up and down with great vigour. At present the performance has the attraction of novelty, but we doubt whether it will have a lasting success.”

And in 1809 one Jack Matthews offered a “dog Hamlet,” in which “the Prince of Denmark in every scene was attended by a large black dog, and in the last, the sagacious animal took upon himself the office of executioner by springing upon the king and putting an end to his wicked career in the usual orthodox fashion.”

Punch noted, “Yet surely the play has seldom been acted without the assistance of a great Dane.”

In 2004, listeners of the BBC’s Today program voted Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” the “saddest classical” work ever written, earning 52.1% of the vote and surpassing “Dido’s Lament” (20.6%) from Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, the Adagietto (12.3%) from Gustav Mahler’s fifth symphony, Richard Strauss’ Metamorphosen (5.1%), and “Gloomy Sunday” as sung by Billie Holiday (9.8%).

During the funeral service for Princess Grace of Monaco in 1982, the New York Times noted, “while a part of Samuel Barber’s soaring Adagio for Strings was being played, Prince Albert, who is 24, covered his face in his black-gloved hands. Princess Caroline, who wept, turned towards her father, who sat next to her by the altar, but the Prince [Rainier], partly slumped, eyes half-closed, did not raise his head.” A friend of the prince described him as experiencing “one of the most deep, most total sadnesses” at the loss of his wife.

Barber’s “Adagio” was played at the prince’s own funeral in 2005, and it memorialized the deaths of Sen. Robert A. Taft in 1953, Albert Einstein in 1955, and John Kennedy in 1963. One friend of Barber’s said he heard the music on the radio within 10 minutes of Kennedy’s assassination.

Why do we do this to ourselves? Life is already full of pain; why do we design art to exacerbate it? “If we enjoy the sadness that we claim to feel, then it is not plainly sadness that we are talking of, because sadness is not an enjoyable experience,” writes philosopher Stephen Davies. “On the other hand, if the sadness is unpleasant, we would not seek out, as we do, artworks leading us to feel sad.” How is it possible to enjoy sadness?

(Thomas Larson, The Saddest Music Ever Written, 2012; Stephen Davies, “Why Listen to Sad Music If It Makes One Feel Sad?”, in Jenefer Robinson, ed., Music and Meaning, 1997.)

“You can tell the character of every man when you see how he gives and receives praise.” — Seneca

“To learn a man’s character, mark how he takes a favour.” — Archbishop Richard Whately

“If all else fails, the character of a man can be recognized by nothing so surely as by a jest which he takes badly.” — G.C. Lichtenberg

“To know a man, observe how he wins his object, rather than how he loses it; for when we fail, our pride supports us — when we succeed, it betrays us.” — Charles Caleb Colton

“Judge a man by his questions rather than by his answers.” — Voltaire

If you had to judge by bodily sensations alone, could you distinguish shame from embarrassment? Philosopher William Alston suggests that we need to consult our beliefs in order to do this. “Even if there are in fact subtle differences in the patterns of bodily sensation associated with the two, it seems that what in fact forms the basis of the distinction is that it is necessary for shame but not for embarrassment that the subject take the object to be something which is his fault.”

Similarly, Jerome Shaffer proposes that beliefs are necessary to distinguish admiration from envy. Both involve “the belief that the person who is the object of the emotion has some good, but admiration will involve the belief that the person is worthy of it whereas envy will involve the belief that I am worthy of it instead (or, at least, also).”

Robert Yanal suggests that we might even need to check our beliefs in order to distinguish extreme happiness from extreme sadness. “Since both involve a nearly overwhelming rush of sensation, we might know that we are very happy only when we check our belief that our beloved’s life has been spared, not forfeited.” Sensations themselves are not enough to identify the emotion. “Typically, belief or a belief surrogate is brought in to draw the distinctions that we think must be drawn.”

Alston adds that “the presence of such evaluations seems to be what makes bodily states and sensations emotional” in the first place. “Some sinkings in the stomach are emotional, because they stem from an evaluation of something as dangerous; other sinkings are not emotional because they stem from indigestion.”

[William Alston, “Emotion and Feeling,” The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 1967; Jerome A. Shaffer, “An Assessment of Emotion,” American Philosophical Quarterly, April 1983; Robert Yanal, Paradoxes of Emotion and Fiction, 1999.]

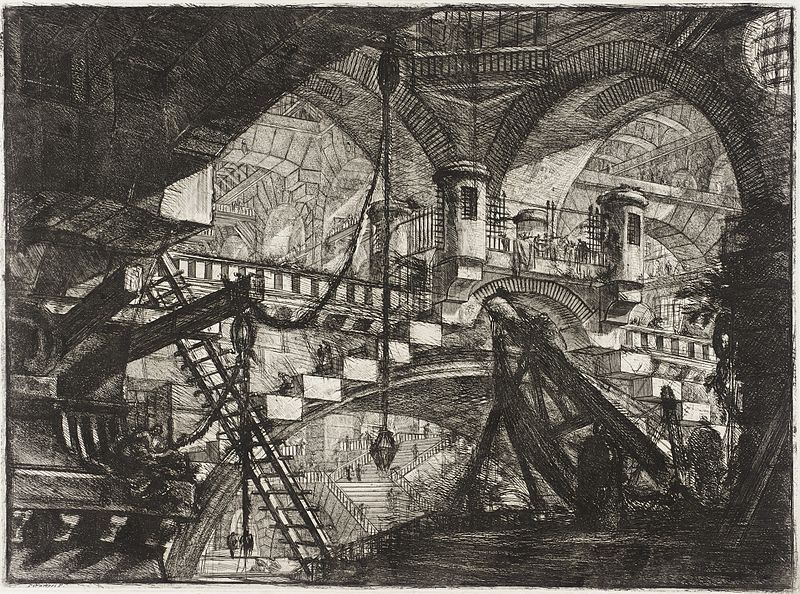

Is the proposition ‘Botticelli’s Birth of Venus depicts the birth of Venus’ true, false, or neither true nor false? If we assume that there never was such an event as the actual birth of Venus (as we safely can), then this proposition would appear to be analogous to ‘Alexander slew the Minotaur.’ But this proposition is true: Botticelli’s Birth of Venus does depict the birth of Venus.

— W.E. Kennick of Amherst College, posed in Margaret P. Battin et al., Puzzles About Art, 1989