Author: Greg Ross

Diplomacy

The index for Hugh Vickers’ 1985 book Great Operatic Disasters contains an entry for which no page numbers are given:

Incompetence — better not specified

Solo

A poignant little detail from my podcast research on Maurice Wilson, who in 1934 set out to climb Everest alone:

There was only one precedent in mountaineering history for such an impossible lone assault. In May of 1929 a young American climber, E.F. Farmer of New Rochelle, N.Y., had set off from Darjeeling on a suicidal attack on 28,146-foot Kangchenjunga. He disappeared into the clouds and was never seen again.

(John Cottrell, “The Madman of Everest,” Sports Illustrated, April 30, 1973.)

One Solution

[Jerome Sankey] challenged Sir William [Petty] to fight with him. Sir William is extremely short-sighted, and being the challengee it belonged to him to nominate place and weapon. He nominates for the place a dark cellar, and the weapon to be a great carpenter’s axe. This turned the knight’s challenge into ridicule, and so it came to nought.

— John Aubrey, Brief Lives, 1697

The Willoughby Postdiction

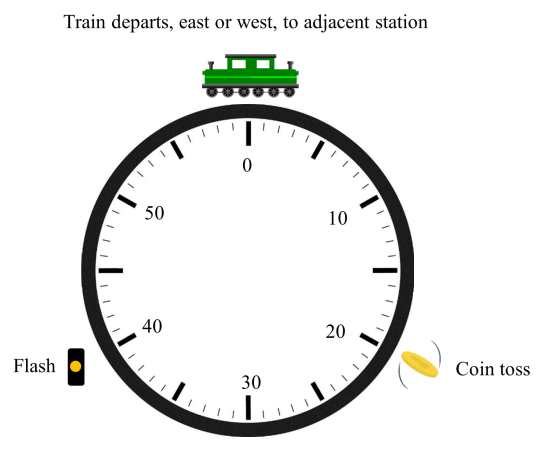

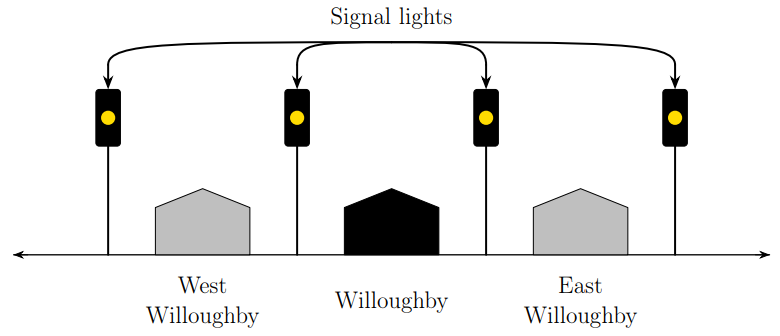

A train line extends infinitely far east and west. Stations are spaced a mile apart, and midway between each pair of stations is a signal light. There’s one train on the line, and it moves to an adjacent station at the top of each hour. Its choice (east or west) is determined by the engineer, who flips a coin 20 minutes after each hour. If the coin lands heads, the train’s next destination will be the station one mile east. If it lands tails, the train will next go to the station one mile west.

Forty minutes after each hour, one of the infinitely many signal lights will flash. The flash is visible all along the line. The identity of the flashing light is random, and it’s unrelated to the coin toss.

You wake up on this train while it’s stopped at a station. It’s 2:30 p.m., which means the engineer flipped his coin 10 minutes ago. The conductor tells you that the next destination is Willoughby. A map tells you that the Willoughby station is flanked by East Willoughby and West Willoughby, so you must be at one of these two stations, but you don’t know which one. Because these are the only two possibilities and there’s no reason for one to be more likely, you conclude that they’re equally probable.

Before the train departs at 3 p.m., is it possible to guess the outcome of the engineer’s coin toss at 2:20 p.m. with success probability greater than 1/2? El Camino College mathematician Leonard M. Wapner contends that it is. At 2:40 p.m. a signal light will flash. There’s a nonzero probability p that the light that flashes will be one of the two lights adjacent to the Willoughby station. If that happens, it will indicate with certainty the direction of Willoughby (east or west) from your current location. The chance that the flash doesn’t come from one of these two lights is 1 – p, and in that case the chance is 1/2 that it comes from the direction of Willoughby. Overall:

“So,” Wapner writes, “if the light flashes to your east, you would guess that the train will be departing to the east and that the engineer’s coin landed heads. If the light flashes to the west, you would guess that the train will depart to the west and that the engineer’s coin landed tails. You should expect your guess (east/heads or tails/west) to be successful more often than not.”

(He adds, “The Willoughby prediction scheme, though mathematically valid, is far too contrived for it to be achieved in actuality. But there being no mathematical contradictions, the door remains open to variations and applications.”)

(Leonard M. Wapner, “Beyond Chance: Predicting the Unpredictable,” Recreational Mathematics Magazine 12:21 [December 2025], 1-8.)

“WIPEOUT!”

Cynthia Knight composed this in 1983 — a poem typed entirely on the upper row of a typewriter:

O WOE

(we quote you, poor poet)

We tiptoe up, quiet. You peer out. You opt to write

quite proper poetry

to pour out your pretty repertoire.

We try to woo you to write. You pop out; retire to pout.

Torpor? Terror? Ire? Or worry? We pity you, poor poet.

Put out, you rip your poetry up. Too trite?

We try to pique you.

Were your pep to tire, or your power to rot

We prop you up to retype it.

Or were our top priority to trip you

or were etiquette, piety, or propriety to require you to wire up your typewriter to rewrite it …

O! You write witty quip, pert retort. You titter. You write pure, utter tripe too, I purr.

You err

retype your error

weep

wipe your wet typewriter (your property)

We TOWER o’er you, wee tot — were you TWO?

YOU WORE YOUR TOY TYPEWRITER OUT!

We quit.

(“The Poet’s Corner,” Word Ways 16:2 [May 1983], 87-88.)

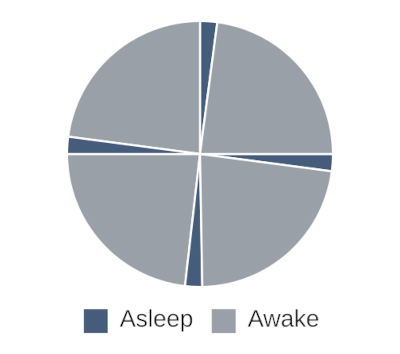

Dymaxion Sleep

In 1943 Buckminster Fuller announced that he’d been getting by on two hours of sleep a day. Each person has a primary and a secondary store of energy, he said; the first is restored quickly and the second takes longer. The trick, then, is to relax as soon as you’ve used up the primary store. Fuller trained himself to take a nap at the first sign of fatigue, which he found happened about every six hours. Taking a half-hour nap at those times left him in “the most vigorous and alert condition I have ever enjoyed,” he said.

“For two years Fuller thus averaged two hours of sleep in 24,” Time reported, adding, “Life-insurance doctors who examined him found him sound as a nut.” Fuller said he’d had to abandon the plan because it conflicted with his coworkers’ schedules. “But he wishes the nation’s ‘key thinkers’ could adopt his schedule; he is convinced it would shorten the war.”

Mixed Doubles

In a letter to Maud Standen dated Dec. 18, 1877, Lewis Carroll included a puzzle:

[M]y ‘Anagrammatic Sonnet’ will be new to you. Each line has 4 feet, and each foot is an anagram, i. e., the letters of it can be re-arranged so as to make one word. Thus there are 24 anagrams, which will occupy your leisure moments for some time, I hope. Remember, I don’t limit myself to substantives, as some do. I should consider ‘we dishwished’ a fair anagram.

As to the war, try elm. I tried.

The wig cast in, I went to ride.

‘Ring? Yes.’ We rang. ‘Let’s rap.’ We don’t.

‘O shew her wit!’ As yet she won’t.

Saw eel in Rome. Dry one: he’s wet.

I am dry. O forge! Th’rogue! Why a net?

For example, the first foot in the first line, “As to,” can be rearranged to spell OATS. Carroll left no solution, but he did add a parting riddle to which we have the answer:

“To these you may add ‘abcdefgi,’ which makes a compound word — as good a word as ‘summer-house.'” What is it?

In a Word

tesserarian

adj. pertaining to play

aspernate

v. to scorn

absit

n. a student’s temporary leave of absence

denegate

v. to deny or refuse

In 1873, when the University of Michigan challenged Cornell to the new game of football, Cornell president Andrew D. White declined. He said, “I will not permit thirty men to travel four hundred miles to agitate a bag of wind.”

“History Talks Too Little About Animals”

“Jottings” from the notebooks of Bulgarian novelist Elias Canetti, published as The Human Province (1978):

- The days are distinct, but the night has only one name.

- A war always proceeds as if humanity had never hit upon the notion of justice.

- The lowest man: he whose wishes have all come true.

- The dead are nourished by judgments, the living by love.

- If you have seen a person sleeping, you can never hate him again.

- I really only know what a tiger is since Blake’s poem.

- A nice trick: throwing something into the world without being pulled in by it.

- The future, which changes every instant.

- I’m fed up with seeing through people; it’s so easy, and it gets you nowhere.

- In love, assurances are practically an announcement of their opposite.

- In eternity, everything is at the beginning, a fragrant morning.

- Praying as a rehearsal of wishes.

- Why aren’t more people good out of spite?

- The best person ought not to have a name.

- To keep thoughts apart by force. They all too easily become matted, like hair.

- Each war contains all earlier wars.

- One may have known three or four thousand people, one speaks about only six or seven.

- You notice some things only because they’re not connected to anything.

- Everyone ought to watch himself eating.

- Nothing is more boring than to be worshiped. How can God stand it?

“Square tables: the self-assurance they give you, as though one were alone in an alliance of four.”