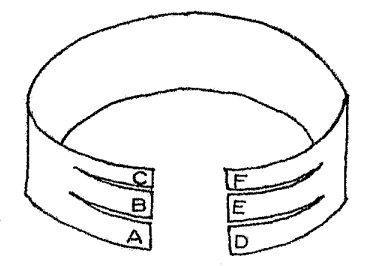

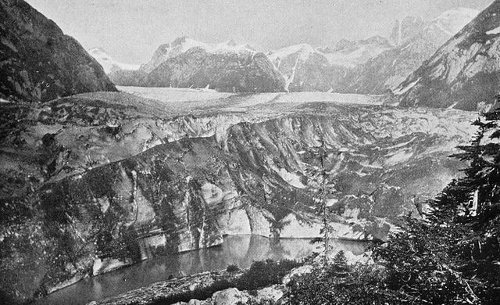

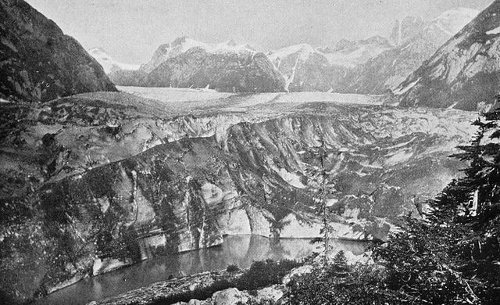

One day in 1880 John Muir set out to explore a glacier in southeastern Alaska, accompanied by Stickeen, the dog belonging to his traveling companion. The day went well, but on their way back to camp they found their way blocked by an immense 50-foot crevasse crossed diagonally by a narrow fin of ice. After long deliberation Muir cut his way down to the fin, straddled it and worked his way perilously across, but Stickeen, who had shown dauntless courage throughout the day, could not be convinced to follow. He sought desperately for some other route, gazing fearfully into the gulf and “moaning and wailing as if in the bitterness of death.” Muir called to him, pretended to march off, and finally ordered him sternly to cross the bridge. Miserably the dog inched down to the farther end and, “lifting his feet with the regularity and slowness of the vibrations of a seconds pendulum,” crept across the abyss and scrambled up to Muir’s side.

And now came a scene! ‘Well done, well done, little boy! Brave boy!’ I cried, trying to catch and caress him; but he would not be caught. Never before or since have I seen anything like so passionate a revulsion from the depths of despair to exultant, triumphant, uncontrollable joy. He flashed and darted hither and thither as if fairly demented, screaming and shouting, swirling round and round in giddy loops and circles like a leaf in a whirlwind, lying down, and rolling over and over, sidewise and heels over head, and pouring forth a tumultuous flood of hysterical cries and sobs and gasping mutterings. When I ran up to him to shake him, fearing he might die of joy, he flashed off two or three hundred yards, his feet in a mist of motion; then, turning suddenly, came back in a wild rush and launched himself at my face, almost knocking me down, all the while screeching and screaming and shouting as if saying, ‘Saved! saved! saved!’ Then away again, dropping suddenly at times with his feet in the air, trembling and fairly sobbing. Such passionate emotion was enough to kill him. Moses’ stately song of triumph after escaping the Egyptians and the Red Sea was nothing to it. Who could have guessed the capacity of the dull, enduring little fellow for all that most stirs this mortal frame? Nobody could have helped crying with him!

Thereafter, Muir wrote, “Stickeen was a changed dog. During the rest of the trip, instead of holding aloof, he always lay by my side, tried to keep me constantly in sight, and would hardly accept a morsel of food, however tempting, from any hand but mine. At night, when all was quiet about the camp-fire, he would come to me and rest his head on my knee with a look of devotion as if I were his god. And often as he caught my eye he seemed to be trying to say, ‘Wasn’t that an awful time we had together on the glacier?'”