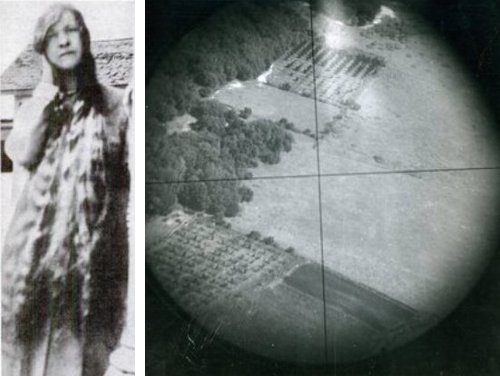

In 1943, Colorado broom factory worker Mary Babnik Brown saw an advertisement in a Pueblo newspaper soliciting blond hair, at least 22 inches long, that had not been treated with chemicals or hot irons. Brown had never cut her hair, which she combed twice a day and washed twice a week with pure soap. When her samples were deemed acceptable, she cut off all 34 inches and sent it in, considering this her contribution to the war effort, though “I cried for two months.”

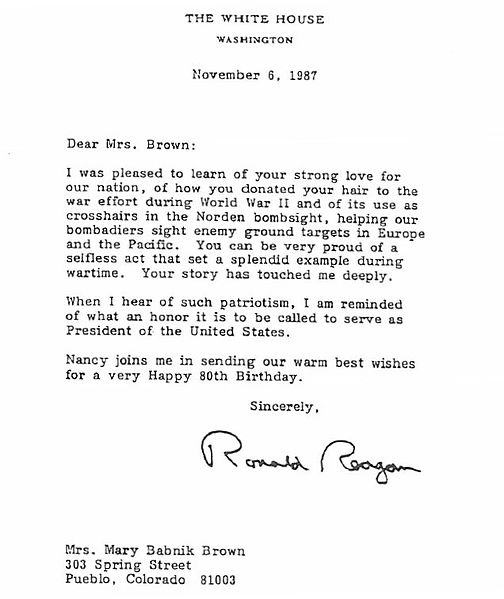

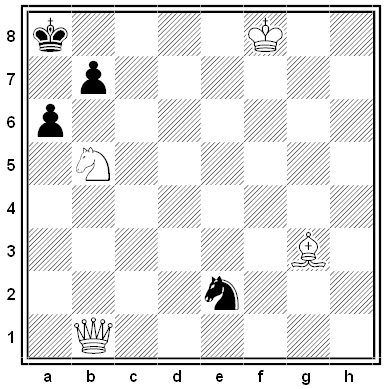

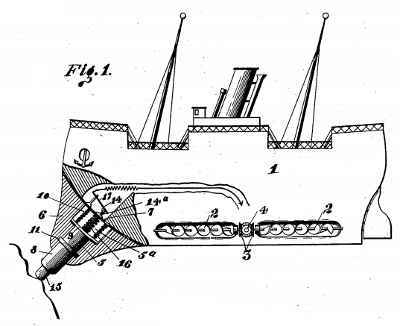

At the time she was told that her hair would be used in meteorological instruments. It wasn’t until 1987, the year of her 80th birthday, that she learned that it had been used in the Norden bombsight, a top-secret instrument that guided bombs to their targets. Engineers had determined that fine blond human hair worked ideally in crosshairs, but the technology was a closely guarded secret, so the donors weren’t told how their contributions would be used. “I couldn’t believe it when they told me,” Brown said. “All I knew was that they needed virgin hair.”

She did get some compensation: Pueblo declared Nov. 22, 1991, “Mary Babnik Brown Day,” she was inducted into the Colorado Aviation Historical Society’s hall of fame, and Ronald Reagan sent her this letter: