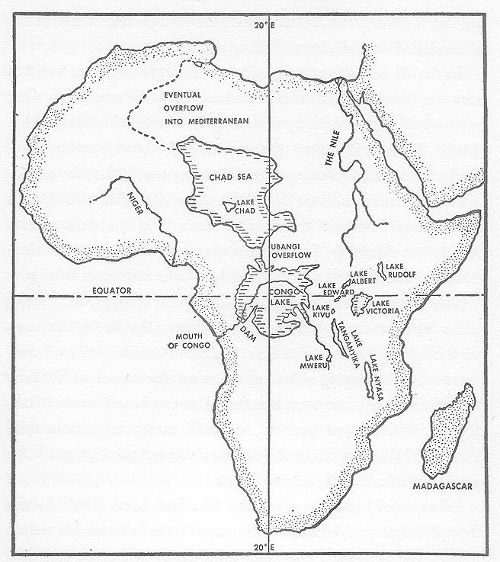

German architect Herman Sörgel’s plan to drain the Mediterranean was only the beginning — he also wanted to irrigate Africa by creating an enormous pair of artificial seas. By damming the Congo River he would create a gigantic lake in the center of the continent; he calculated that this would cause the Ubangi River to reverse its course, flowing northwest into the Chari River and creating a huge “Chad Sea” that would seek an outlet in the north, a “second Nile” that would irrigate Algeria. Between them, these new seas would cover 10 percent of the continent.

Sörgel also wanted to build a giant hydroelectric plant at Stanley Falls whose power could bring light and industry to much of Africa. But the plans came to nothing. “The scale of such a project is beyond colossal and is utterly unfeasible politically,” writes Franklin Hadley Cock in Energy Demand and Climate Change. “Its hydroelectric power potential is staggering, as are the environmental and human problems building it would cause.”