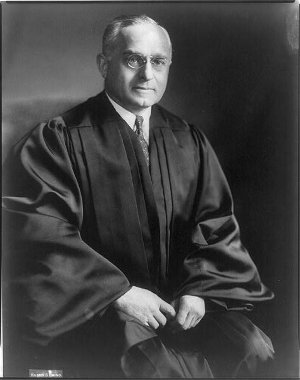

In May 1954, 12-year-old M. Paul Claussen Jr. of Alexandria, Va., sent a letter to Felix Frankfurter saying that he was interested in “going into the law as a career” and requested the jurist’s advice as to “some ways to start preparing myself while still in junior high school.” He received this reply:

My Dear Paul:

No one can be a truly competent lawyer unless he is a cultivated man. If I were you, I would forget all about any technical preparation for the law. The best way to prepare for the law is to come to the study of the law as a well-read person. Thus alone can one acquire the capacity to use the English language on paper and in speech and with the habits of clear thinking which only a truly liberal education can give. No less important for a lawyer is the cultivation of the imaginative faculties by reading poetry, seeing great paintings, in the original or in easily available reproductions, and listening to great music. Stock your mind with the deposit of much good reading, and widen and deepen your feelings by experiencing vicariously as much as possible the wonderful mysteries of the universe, and forget about your future career.

With good wishes,

Sincerely yours,

Felix Frankfurter