Author: Greg Ross

In the Dark

From The Black-Out Book, a book of entertainments to amuse Londoners during the air-raid blackouts of 1939:

When a certain commodity was rationed, a woman wrote to her tradesman asking his advice.

He replied:

If the B mt, put :

If the B . putting :

What was the commodity, and what did he mean?

Top Secret

The Treaty of Berlin was drafted in secrecy, so its framers were astonished to find it published in the London Times. Journalist Henri de Blowitz at first refused to reveal his source, but at last relented near the end of his life. Well before the congress started he had attached a confederate to the clerical staff, but the man felt he was being watched, so the two could not dare to meet or talk. Finally de Blowitz noticed that they wore hats of the same type and color, and he hit on a plan of “childish simplicity.”

De Blowitz was staying at the Kaiserhof. Each day his confederate went there for lunch and dinner. The two never acknowledged one another, but they hung their hats on neighboring pegs. At the end of the meal the confederate departed with de Blowitz’s hat, and de Blowitz innocently took the confederate’s. The communications were hidden in the hat’s lining.

“Only twice were we forced to put off the communication till the following day,” de Blowitz wrote in his 1904 memoir. “Once, however, we had a scare.”

“One of my English colleagues, on leaving the dining-room, made a mistake and took my friend’s hat. Without looking at each other we felt, as he wrote me next day, that we turned pale. If the colleague in question had kept the hat, he might have discovered the third article of the treaty, which had been adopted at the previous day’s sitting, and also a hint of the difficulties that had arisen between Russia and England on the question of the boundaries of Bulgaria, and very disagreeable consequences for my friend might have been the result. Fortunately, on reaching the door, the Englishman put on the hat, which dropped over on his nose. He laughingly took it off and replaced it on its peg. I had risen to take the hat from him, but sat down again. I breathed freely, and my friend must have done the same.”

In a Word

oche

n. the line behind which darts players must stand

aimcrier

n. a person who cries “Aim!” to an archer; an applauder or encourager

Sudden Stop

Anthropologist George Bird Grinnell’s The Fighting Cheyennes (1915) describes “perhaps the only attempt to disable a railroad ever made by Indians.” A Cheyenne named Porcupine relates that in late summer 1867, after an embittering loss to U.S. soldiers in frontier Nebraska, his band witnessed “the first train of cars that any of us had seen. We looked at it from a high ridge. Far off it was very small, but it kept coming and growing larger all the time, puffing out smoke and steam, and as it came on we said to each other that it looked like a white man’s pipe when he was smoking.”

“Not long after this, as we talked of our troubles, we said among ourselves: ‘Now the white people have taken all we had and have made us poor and we ought to do something. In these big wagons that go on this metal road, there must be things that are valuable — perhaps clothing. If we could throw these wagons off the iron they run on and break them open, we should find out what was in them and could take whatever might be useful to us.”

They lay a stick across the tracks, which was enough to upset a handcar that appeared that night, and the Cheyenne killed the two men who had been working it. Encouraged, they used levers to pull out the spikes at the end of a rail and bent it a foot or two in the air. Presently they spotted two trains approaching and sent a party to assail the first one.

“When they fired, the train made a loud noise — puffing — and threw up sparks into the air, going faster and faster, until it reached the break, and the locomotive jumped into the air and the cars all came together. After the train was wrecked, a man with a lantern was seen coming running along the track, swearing in a loud tone of voice. He was the only one on the train left alive. They killed him. The other train stopped somewhere far off and whistled. Four or five men came walking along the track toward the wrecked train. The Cheyennes did not attack them. The second train then backed away.”

The Cheyenne would shortly be driven out of that country, but they relished this victory. “Next morning they plundered and burned the wrecked train and scattered the contents of the cars all over the prairie,” Porcupine relates. “They tied bolts of calico to their horses’ tails, and galloped about and had much amusement.”

Diamonds and Pearls

Yet more aphorisms from German physicist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg:

- “The most perfect ape cannot draw an ape; only man can do that; but, likewise, only man regards the ability to do this as a sign of superiority.”

- “A book which, above all others in the world, should be forbidden, is a catalogue of forbidden books.”

- “The motives that lead us to do anything might be arranged like the thirty-two winds and might be given names on the same pattern: for instance, ‘bread-bread-fame’ or ‘fame-fame-bread.'”

- “We accumulate our opinions at an age when our understanding is at its weakest.”

- “Once the good man was dead, one wore his hat and another his sword as he had worn them, a third had himself barbered as he had, a fourth walked as he did, but the honest man that he was — nobody any longer wanted to be that.”

- “With most men, unbelief in one thing springs from blind belief in another.”

- “We say that someone occupies an official position, whereas it is the official position that occupies him.”

- “There are very many people who read simply to prevent themselves from thinking.”

- “With prophecies the commentator is often a more important man than the prophet.”

- “Delight at having understood a very abstract and obscure system leads most people to believe in the truth of what it demonstrates.”

- “There is no greater impediment to progress in the sciences than the desire to see it take place too quickly.”

- “There is no more important rule of conduct in the world than this: attach yourself as much as you can to people who are abler than you and yet not so very different that you cannot understand them.”

- “What is the good of drawing conclusions from experience? I don’t deny we sometimes draw the right conclusions, but don’t we just as often draw the wrong ones?”

- “When a book and a head collide and a hollow sound is heard, must it always have come from the book?”

Ahem

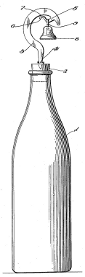

It’s easy to send out a message in a bottle, but it’s hard to get anyone to notice it. In 1922 Hannah Rosenblatt sought to remedy this by adding a bell:

It will be seen that I provide a carrier that will positively float until washed upon shore or picked up by a passing boat. The peculiar shape of the support in combination with the bell assures the attraction of attention which is a very important feature of my invention.

Rosenblatt lived in the Philippines — perhaps there’s a story behind this.

Unquote

“We often want one thing and pray for another, not telling the truth even to the gods.” — Seneca

“O! Wherefore”

Robert Peter wrote these lines on March 23, 1838, on leaving London for Jamaica. Christopher Adams named Peter one of the worst English poets, presumably for the immortal last line.

O! wherefore pensive heaves that sigh?

Why is thy face o’ercast with sorrow?

Thy throbbing bosom heaving high;

And wherefore should thy grief-dimmed eye

That tint of melancholy borrow?

‘Tis thus with me; I cherish dear

Each fond memorial of affection;

My heart the impress still shall wear —

Though fate doth now asunder tear

Those ties, the cause of my dejection.

For soon the dark, deep, rolling waves

Of wild Atlantic shall us sever;

And while around me ocean raves,

Still warm remembrance friendship craves;

Thee, M.M. Woods, forget I’ll never!

A Mobile Fort

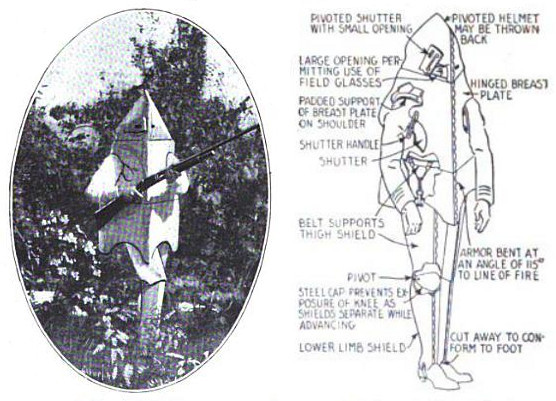

Inventor Otis L. Boucher offered this steel suit to American troops during World War I. Each of the seven pieces presents an angled front to the enemy, in hopes of deflecting bullets, and the padded helmet can be thrown back when necessary.

“Since … helmets have unquestionably proved their merit, particularly as a defense against bursting shrapnel, why not go a step farther?” approved Popular Science Monthly. “Why protect only the head? Why not the whole body?”