oche

n. the line behind which darts players must stand

aimcrier

n. a person who cries “Aim!” to an archer; an applauder or encourager

oche

n. the line behind which darts players must stand

aimcrier

n. a person who cries “Aim!” to an archer; an applauder or encourager

Anthropologist George Bird Grinnell’s The Fighting Cheyennes (1915) describes “perhaps the only attempt to disable a railroad ever made by Indians.” A Cheyenne named Porcupine relates that in late summer 1867, after an embittering loss to U.S. soldiers in frontier Nebraska, his band witnessed “the first train of cars that any of us had seen. We looked at it from a high ridge. Far off it was very small, but it kept coming and growing larger all the time, puffing out smoke and steam, and as it came on we said to each other that it looked like a white man’s pipe when he was smoking.”

“Not long after this, as we talked of our troubles, we said among ourselves: ‘Now the white people have taken all we had and have made us poor and we ought to do something. In these big wagons that go on this metal road, there must be things that are valuable — perhaps clothing. If we could throw these wagons off the iron they run on and break them open, we should find out what was in them and could take whatever might be useful to us.”

They lay a stick across the tracks, which was enough to upset a handcar that appeared that night, and the Cheyenne killed the two men who had been working it. Encouraged, they used levers to pull out the spikes at the end of a rail and bent it a foot or two in the air. Presently they spotted two trains approaching and sent a party to assail the first one.

“When they fired, the train made a loud noise — puffing — and threw up sparks into the air, going faster and faster, until it reached the break, and the locomotive jumped into the air and the cars all came together. After the train was wrecked, a man with a lantern was seen coming running along the track, swearing in a loud tone of voice. He was the only one on the train left alive. They killed him. The other train stopped somewhere far off and whistled. Four or five men came walking along the track toward the wrecked train. The Cheyennes did not attack them. The second train then backed away.”

The Cheyenne would shortly be driven out of that country, but they relished this victory. “Next morning they plundered and burned the wrecked train and scattered the contents of the cars all over the prairie,” Porcupine relates. “They tied bolts of calico to their horses’ tails, and galloped about and had much amusement.”

Yet more aphorisms from German physicist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg:

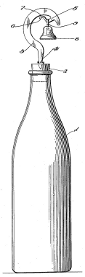

It’s easy to send out a message in a bottle, but it’s hard to get anyone to notice it. In 1922 Hannah Rosenblatt sought to remedy this by adding a bell:

It will be seen that I provide a carrier that will positively float until washed upon shore or picked up by a passing boat. The peculiar shape of the support in combination with the bell assures the attraction of attention which is a very important feature of my invention.

Rosenblatt lived in the Philippines — perhaps there’s a story behind this.

“We often want one thing and pray for another, not telling the truth even to the gods.” — Seneca

Robert Peter wrote these lines on March 23, 1838, on leaving London for Jamaica. Christopher Adams named Peter one of the worst English poets, presumably for the immortal last line.

O! wherefore pensive heaves that sigh?

Why is thy face o’ercast with sorrow?

Thy throbbing bosom heaving high;

And wherefore should thy grief-dimmed eye

That tint of melancholy borrow?

‘Tis thus with me; I cherish dear

Each fond memorial of affection;

My heart the impress still shall wear —

Though fate doth now asunder tear

Those ties, the cause of my dejection.

For soon the dark, deep, rolling waves

Of wild Atlantic shall us sever;

And while around me ocean raves,

Still warm remembrance friendship craves;

Thee, M.M. Woods, forget I’ll never!

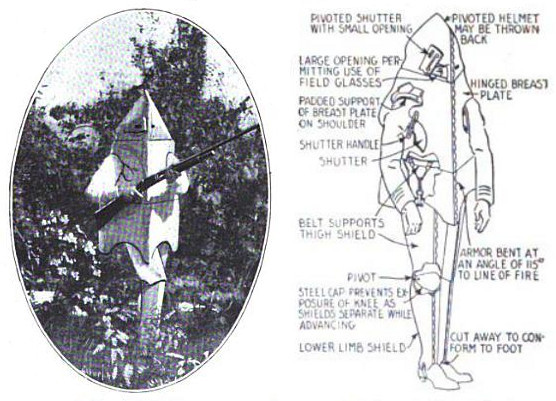

Inventor Otis L. Boucher offered this steel suit to American troops during World War I. Each of the seven pieces presents an angled front to the enemy, in hopes of deflecting bullets, and the padded helmet can be thrown back when necessary.

“Since … helmets have unquestionably proved their merit, particularly as a defense against bursting shrapnel, why not go a step farther?” approved Popular Science Monthly. “Why protect only the head? Why not the whole body?”

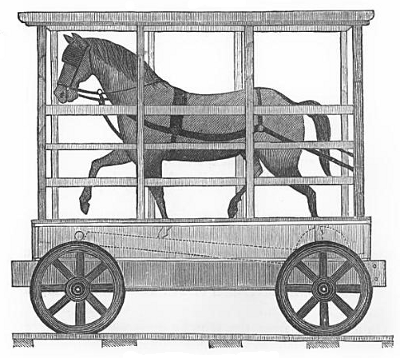

William Henry Brown’s The History of the First Locomotives in America (1871) describes two unlikely competitors that steam had to contend with on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. In the first, a horse was placed in the car and made to walk on a belt that drove the wheels. “The machine worked indifferently well; but, on one occasion, when drawing a car filled with editors and other representatives of the press, it ran into a cow, and the passengers, having been tilted out and rolled down an embankment, were naturally enough unanimous in condemning the contrivance.”

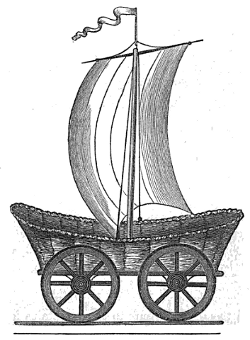

The second was a wind-driven car rather optimistically called the Meteor. This would run only when the wind was behind it, and the inventor “was afraid to trust a strong side-wind lest the vehicle might be upset; so it rarely made its appearance except a northwester was blowing, when it would be dragged out to the farther end of the Mount Clair embankment, and come back, literally with flying colors.”

“Like the horse-car, the sailing-car had its day. It was an amusing toy — nothing more — and is referred to now as an illustration of the crudity of the ideas prevailing forty years ago in reference to railroads.”

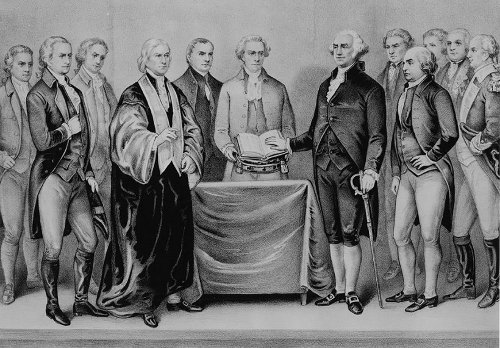

The U.S. Constitution requires that the president be at least 35 years old. But legal scholar Mark V. Tushnet imagines a loophole by which, say, a 16-year-old guru might be elected:

“Suppose that the guru’s supporters sincerely claim that their religion includes among its tenets a belief in reincarnation. Even on the narrowest definition of ‘age,’ they say, their guru is well over thirty-five years old even though the guru emerged from the latest womb sixteen years ago.

“Further, it would have been an establishment of religion for the President of the Senate to reject their definition of ‘age,’ and it would violate their rights under the free exercise clause … for the courts to overturn the decision made by the political branches.”

His point is that even the most seemingly straightforward provisions in the Constitution can require interpretation.

(“Interpretation Symposium: Constitutional Interpretation: Comment: A Note on the Revival of Textualism in Constitutional Theory,” Southern California Law Review, January 1985)

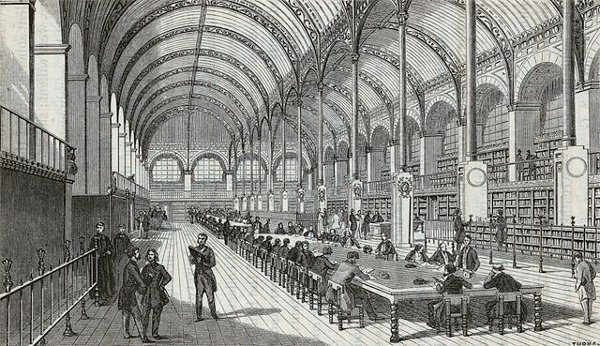

Finally, consider what delightful teaching there is in books. How easily, how secretly, how safely in books do we make bare without shame the poverty of human ignorance! These are the masters that instruct us without rod and ferrule, without words of anger, without payment of money or clothing. Should ye approach them, they are not asleep; if ye seek to question them, they do not hide themselves; should ye err, they do not chide; and should ye show ignorance, they know not how to laugh. O Books! ye alone are free and liberal. Ye give to all that seek, and set free all that serve you zealously. By what thousands of things are ye figuratively recommended to learned men in the Scripture given us by Divine inspiration!

— Richard de Bury, Philobiblon, 1344