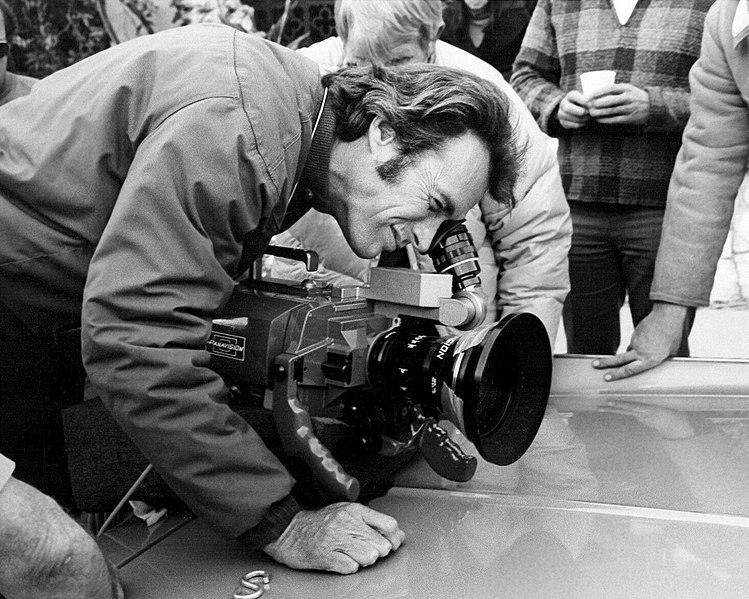

“Instead of saying ‘cut’ at the end of a take, he would say, ‘That’s enough of that shit.’ After your own close-up, it’s hilarious, but when I saw him doing it to himself, it really made me laugh.” — Laura Dern, of Clint Eastwood

“Instead of saying ‘cut’ at the end of a take, he would say, ‘That’s enough of that shit.’ After your own close-up, it’s hilarious, but when I saw him doing it to himself, it really made me laugh.” — Laura Dern, of Clint Eastwood

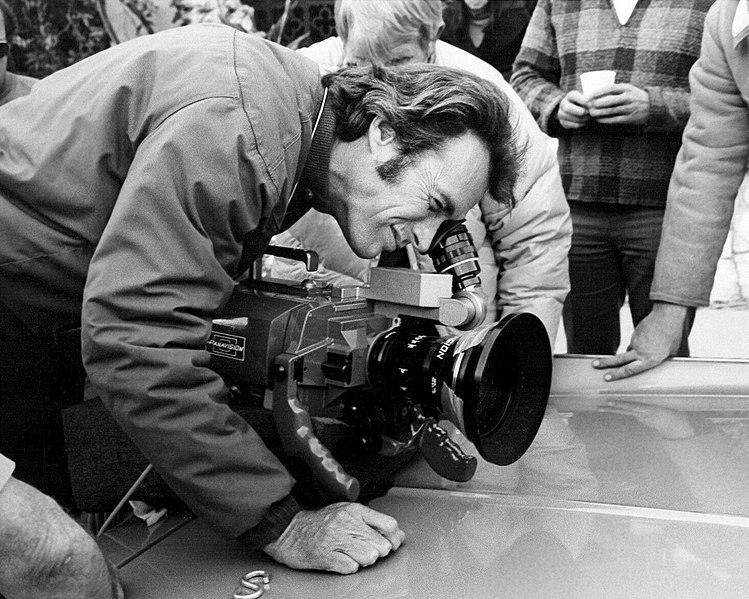

“Home is the only place where you can go out and in. There are places you can go into, and places you can go out of, but the one place, if you do but find it, where you may go out and in both, is home.” — George MacDonald

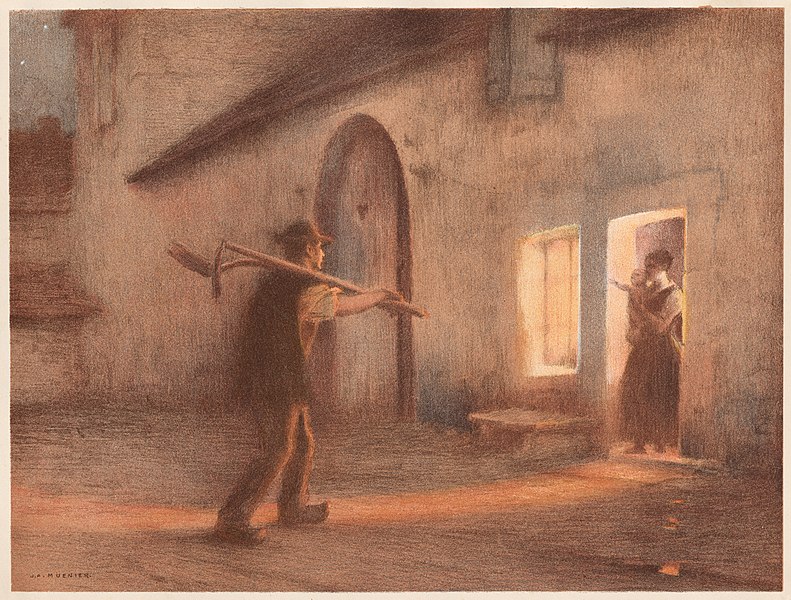

Suppose you have a publicity-seeking inchworm and want to keep him to yourself. What’s the smallest cover you can contrive to keep him hidden? He can writhe into any shape that an inch-long creature can take; you must always be able to turn your shape to keep him covered.

Strangely, we don’t yet know the answer to this question. Mathematician Leo Moser first posed it in 1966, and various proposals have driven the upper bound as low as π/12 ≈ 0.2618, but we still don’t know whether smaller covers are possible. It’s known as Moser’s worm problem.

It’s true, you’re right; there is no rhyme.

The effort is a waste of time.

I happily concede defeat.

But oranges were made to eat,

And not to rhyme; I find it more enj-

oyable to eat the orange.

— James H. Rhodes

From W.H. Auden’s 1970 commonplace book A Certain World:

David Hartley offered a vest-pocket edition of his moral and religious philosophy in the formula W = F2/L, where W is the love of the world, F is the fear of God, and L is the love of God. It is necessary to add only this. Hartley said that as one grows older L increases and indeed becomes infinite. It follows then that W, the love of the world, decreases and approaches zero.

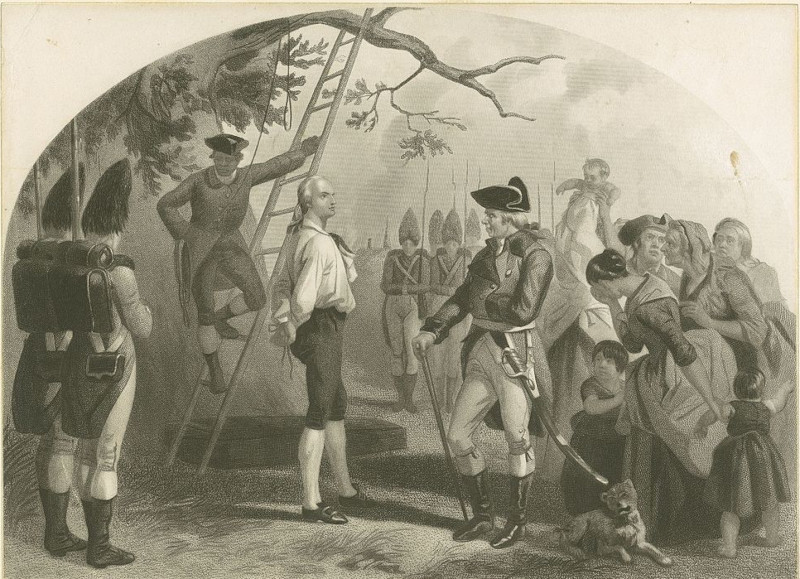

“To read History is to run the risk of asking, ‘Which is more honorable? To rule over people, or to be hanged?'” — J.G. Seume

At the start of H.G. Wells’ 1895 novella The Time Machine, the Time Traveller explains to his friends that “any real body must have extension in four directions: it must have Length, Breadth, Thickness, and — Duration.” This idea, of conceiving time as a fourth dimension, had been broached in the 18th century, but it had first been treated seriously in a mysterious letter to Nature in 1885:

“I [propose] to consider Time as a fourth dimension of our existence. … Since this fourth dimension cannot be introduced into space, as commonly understood, we require a new kind of space for its existence, which we may call time-space.”

The letter writer identified himself only as “S.” Was this Wells? Apparently not: In his 1934 Experiment in Autobiography Wells wrote, “In the universe in which my brain was living in 1879 there was no nonsense about time being space or anything of that sort. There were three dimensions, up and down, fore and aft and right and left, and I never heard of a fourth dimension until 1884 or there-about. Then I thought it was a witticism.”

So someone had anticipated Wells’ idea by a full decade. As far as I know, his identity has never been discovered.

(Via Paul J. Nahin, Holy Sci-Fi!, 2014.)

Fictitious correspondents invented by T.S. Eliot in kick-starting a letters page in The Egoist in 1917:

The Rev. Charles James Grimble

Muriel A. Schwarz

Charles Augustus Conybeare

Helen B. Trundlett

J.A.D. Spence

Apparently this wasn’t unusual for Eliot, who wrote for The Tyro in 1921 as Gus Krutzsch. When I.A. Richards invited Krutzsch to meet him in Peking, Eliot replied, “I do not care to visit any country which has no native cheese.”

As a hedge against hard times, W.C. Fields used to open bank accounts under assumed names, including Sneed Hearn, Dr. Otis Guelpe, Figley E. Whitesides, and Professor Curtis T. Bascom.

“He had bank accounts, or at least safe-deposit boxes, in such cities as London, Paris, Sydney, Cape Town, and Suva,” said his friend Gene Fowler in 1949. “I do not know this for a fact, but I think that much of his fortune still rests in safe-deposit boxes about which, deliberately or not, he said nothing.”

I was in the chair at a most interesting meeting at the Wakefield Asylum last night. It was, too, a curious sensation, sleeping under the same roof as 1,500 lunatics. I was kept awake by thoughts of the kind of sleep that was going on about me. … I made some preliminary remarks on the wide and desolate borderland of cerebral disturbance that lies between sleep and mania.

— Richard Monckton Milnes, letter to Henry Bright, Nov. 26, 1873

George Herrick notes this oddity in his 1997 commonplace book: The record of this U.S. congressional hearing on dirigible disasters contains an inadvertent poem — the encoded weather report for April 3, 1933:

Washington numoil nihilist radnell deadly wabash.

Titusville sanno reflect unripe turfs.

Harrington bonfire gecko unfold.

George felger naked neggins.

Pas roofage gedby gafol.

Havana sorrow mabin caramel.

Father safable oak barfee rogue.

Wichita nineveh mulberry somnific cupsail.

Doucet nightfall naked gargarize birds.

Galveston sirup gullish sacred cupsail.

Sound narford naked ungear seemly.

Antonio surrogate fabella sausage cunette.

Davenport ridgy reflow feugar needs consort.

Birmingham simulate subjoin formosa faints.

Buffalo nightfire ribard gummut gently.

Evansville romulus seahog femme mends control.

Memphis similar suburb gammon medlar wired catsup.

Detroit negative rabate fengone miley currency.

Indianapolis regent seabate formal gently catsup.

Nashville samuda sabula ginmill mexico congregate.

Columbus rugate mallet farmable feline.

Herrick writes, “This particular code has literary flair and one wants the rich prose to read on.”