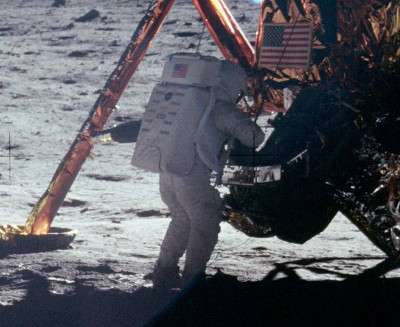

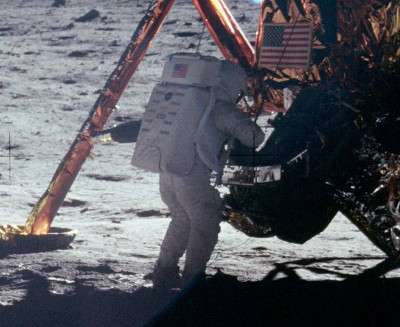

THAT’S ONE SMALL STEP FOR A MAN, ONE GIANT LEAP FOR MANKIND — NEIL ARMSTRONG

is an anagram of

AN EAGLE LANDS ON EARTH’S MOON, MAKING A FIRST SMALL PERMANENT FOOTPRINT

THAT’S ONE SMALL STEP FOR A MAN, ONE GIANT LEAP FOR MANKIND — NEIL ARMSTRONG

is an anagram of

AN EAGLE LANDS ON EARTH’S MOON, MAKING A FIRST SMALL PERMANENT FOOTPRINT

What’s the worst dictionary in the world? It appears to be Webster’s Dictionary of the English Language: Handy School and Office Edition, published in the late 1970s by Book-Craft Guild, Inc. While on vacation in 1994, Christopher McManus of Silver Spring, Md., had to rely on HSOE to arbitrate word games, and he quickly discovered that it had no entry for cow, die, dig, era, get, hat, law, let, may, new, now, off, old, one, run, see, set, top, two, who, why, or you. In fact, of 1,850 common three- and four-letter words that McManus found listed unanimously in seven other dictionaries, HSOE omitted fully 46 percent. At the same time it included such erudite entries as dhow, gyve, pteridophyte, and quipu.

“To find took, one must know to look under take,” McManus writes, “and disc is listed as a variant only at the disk entry.” The volume includes a captioned illustration of a raft, but no entry for raft!

It’s not clear what happened, but McManus suspects that the book was assembled from blocks of typeset copy, about 40 percent of which disappeared during publication. “Since the erstwhile publisher, Book-Craft Guild, is not listed in current publishing directories, definitive explanations are not available.”

(Christopher McManus, “The World’s Worst Dictionary,” Word Ways, February 1995)

(Note that this doesn’t indict all Webster’s dictionaries — most invoke Webster’s name only for marketing purposes.)

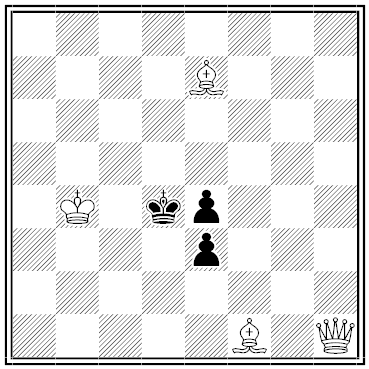

By William Crane Jr., from the Sydney Town and Country Journal, 1877. White to mate in two moves.

Our Geneva Correspondent writes: — ‘A few days since two schoolmasters from Morzine, a Savoyard village near the Swiss frontier, made an excursion to the Col de Coux, not far from Champéry, in the Valais. As they were descending the mountain, late in the afternoon, they thought they heard cries of distress. After a long search they perceived a man holding on to a bush, or small tree, which had struck its roots into the face of the precipice. As the precipice was nearly perpendicular and the man was some 1,200 ft. below them, and the foot of the precipice quite as far below him, they found it impossible to give the poor fellow any help. All they could do was to tell him to stay where he was — if he could — until they came back, and hurry off to Morzine for help. Though it was night when they arrived thither, a dozen bold mountaineers, equipped with ropes, started forthwith for the rescue. After a walk of 12 miles they reached the Col de la Golèse, but it being impossible to scale the rocks in the dark they remained there until the sun rose. As soon as there was sufficient light they climbed by a roundabout path to the top of the precipice. The man was still holding on to the bush. Three of the rescue party, fastened together with cords, were then lowered to a ledge about 600 feet below. From this coign of vantage two of the three lowered the third to the bush. He found the man, who had been seated astride his precarious perch a day and a night, between life and death. It was a wonder how he had been able to hold on so long, for besides suffering from hunger and cold he had been hurt in the fall from the height above. He was a reserve man belonging to Saméons, on his way thither from Lausanne, where he had been working, to be present at a muster. Losing his way on the mountains between Thonon and Saméons, he had missed his footing and rolled over the precipice. He had the presence of mind to cling to the bush, which broke his fall, but if the two schoolmasters had not heard his cries he must have perished miserably. Hoisting him to the top of the precipice was a difficult and perilous undertaking, but it was safely accomplished. None of the man’s hurts were dangerous, and after a long rest and a hearty meal or two he was pronounced fit to continue his journey and report himself at the muster.’

— Times, July 12, 1882

Can objects have preferences? The rattleback is a top that seems to prefer spinning in a certain direction — when spun clockwise, this one arrests its motion, shakes itself peevishly, and then sweeps grandly counterclockwise as if forgiving an insult.

There’s no trick here — the reversal arises due to a coupling of instabilities in the top’s other axes of rotation — but prehistoric peoples have attributed it to magic.

See Right Side Up.

Once, at the chambers of Sir William Jones, while some books were being removed, a large spider dropped upon the floor and Sir William said to Mr. Day, the philanthropist, who stood near him, ‘Kill that spider, Day; kill that spider!’ ‘No,’ said Mr. Day, with that coolness for which he was so conspicuous, ‘I will not kill that spider, Jones; I do not know that I have a right to kill that spider! Suppose when you are going in your coach to Westminster Hall, a superior being who, perhaps, may have as much power over you as you have over this insect, should say to his companion, ‘Kill that lawyer; kill that lawyer!’ how should you like that, Jones? and I am sure to most people a lawyer is a more obnoxious animal than a spider.’

— Thomas Brackett Reed, Modern Eloquence, 1900

In 2004 wind energy company Gamesa Energy UK announced plans to erect a 40-meter test mast in a field outside the Welsh village of Llanfynydd.

The villagers value their seclusion, and the area is home to three endangered bird species — the red kite, the curlew, and the skylark.

So they changed the town’s name to Llanhyfryddawelllehynafolybarcudprindanfygythiadtrienusyrhafnauole, which means “a quiet beautiful village, an historic place with rare kite under threat from wretched blades.”

At 66 letters, this surpassed Anglesey’s Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch as the longest place name in the United Kingdom, attracting some media attention and free publicity for the village’s battle against the energy company.

The change lasted only a week, but it served its purpose. “It might seem that changing the name of the village for the week is a bit of a joke, but we could not be more serious,” villager Meirion Rees told the BBC. “If our community is to be overshadowed it might as well change its name and its identity.”

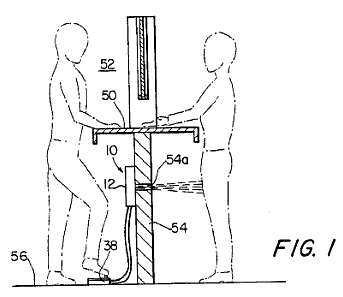

Louis J. Marcone came up with a novel way to catch bank robbers in 1989: The teller might step on a trigger and surreptitiously spray the robber with “a non-toxic, clear, odorless and harmless liquid spray material which can be readily detected by trained police dogs.”

He envisioned a second application for the device: The spray unit could be attached to a fire alarm, so that anyone who pulled the alarm would be marked with the scent. “If the alarm was determined to be a false alarm, the fire department can alert police to bring trained police dogs to the scene, whereupon the dog can track the scent from the alarm location to the person activating the false alarm.”

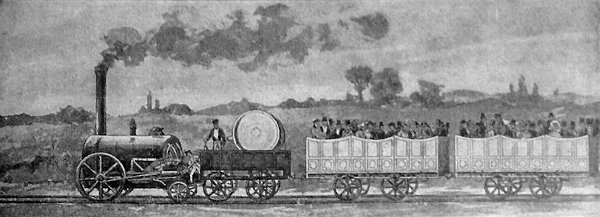

Fanny Kemble meets an early steam locomotive on the Liverpool-Manchester railway, Aug. 25, 1830:

We were introduced to the little engine which was to drag us along the rails. She (for they make these curious little fire horses all mares) consisted of a boiler, a stove, a platform, a bench, and behind the bench a barrel containing enough water to prevent her being thirsty for fifteen miles, the whole machine not bigger than a common fire engine. She goes upon two wheels, which are her feet, and are moved by bright steel legs called pistons; these are propelled by steam, and in proportion as more steam is applied to the upper extremities (the hip-joints, I suppose) of these pistons, the faster they move the wheels; and when it is desirable to diminish the speed, the steam, which unless suffered to escape would burst the boiler, evaporates through a safety valve into the air. The reins, bit, and bridle of this wonderful beast, is a small steel handle, which applies or withdraws the steam from its legs or pistons, so that a child might manage it. The coals, which are its oats, were under the bench, and there was a small glass tube affixed to the boiler, with water in it, which indicates by its fullness or emptiness when the creature wants water, which is immediately conveyed to it from its reservoirs. There is a chimney to the stove, but as they burn coke there is none of the dreadful black smoke which accompanies the progress of a steam vessel. This snorting little animal, which I felt rather inclined to pat, was then harnessed to our carriage, and Mr. Stephenson having taken me on the bench of the engine with him, we started at about ten miles an hour.

The world’s smallest country is smaller than the world’s largest buildings.

Vatican City occupies 44 hectares, or about 4,736,120 square feet.

The Pentagon, by comparison, has a total floor area of 6,636,360 square feet.