Of the 45,000 Union prisoners sent to the Confederate prisoner-of-war camp at Andersonville, Ga., 12,913 died, the victims of starvation, disease, exposure, and abusive guards. Excerpts from the diary of 1st Sgt. John L. Ransom of the Ninth Michigan Cavalry, who was captured in November 1863:

March 14. — Arrived at our destination at last and a dismal hole it is, too. We got off the cars at two o’clock this morning in a cold rain, and were marched into our pen between a strong guard carrying lighted pitch pine knots to prevent our crawling off in the dark. I could hardly walk have been cramped up so long, and feel as if I was a hundred years old. Have stood up ever since we came from the cars, and shivering with the cold. The rain has wet us to the skin and we are worn out and miserable. Nothing to eat to-day, and another dismal night just setting in.

May 19. — Nearly twenty thousand men confined here now. New ones coming every day. Rations very small and very poor. The meal that the bread is made out of is ground, seemingly, cob and all, and it scourges the men fearfully. Things getting continually worse. Hundreds of cases of dropsy. Men puff out of human shape and are perfectly horrible to look at. Philo Lewis died today. Could not have weighed at the time of his death more than ninety pounds, and was originally a large man, weighing not less than one hundred and seventy. Jack Walker, of the 9th Mich. Cavalry, has received the appointment to assist in carrying out the dead, for which service he receives an extra ration of corn bread.

June 8. — More new prisoners. There are now over 23,000 confined here, and the death rate 100 to 130 per day, and I believe more than that. Rations worse.

June 13. — … To-day saw a man with a bullet hole in his head over an inch deep, and you could look down in it and see maggots squirming around at the bottom. Such things are terrible, but of common occurrence. Andersonville seems to be head-quarters for all the little pests that ever originated — flies by the thousand millions.

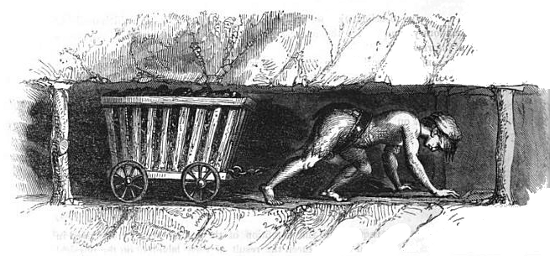

June 28. — It seems to me as if three times as many as ever before are now going off, still I am told that about one hundred and thirty die per day. The reason it seems worse, is because no sick are being taken out now, and they all die here instead of at the hospital. Can see the dead wagon loaded up with twenty or thirty bodies at a time, two lengths, just like four foot wood is loaded on to a wagon at the North, and away they go to the grave yard on a trot. Perhaps one or two will fall off and get run over. No attention paid to that; they are picked up on the road back after more. Was ever before in this world anything so terrible happening? Many entirely naked.

July 6. — Boiling hot, camp reeking with filth, and no sanitary privileges; men dying off over a hundred and forty per day. Stockade enlarged, taking in eight or ten more acres, giving us more room, and stumps to dig up for wood to cook with. …

July 19. — There is no such thing as delicacy here. Nine out of ten would as soon eat with a corpse for a table as any other way. In the middle of last night I was awakened by being kicked by a dying man. He was soon dead. In his struggles he had floundered clear into our bed. Got up and moved the body off a few feet, and again went to sleep to dream of the hideous sights. I can never get used to it as some do. Often wake most scared to death, and shuddering from head to foot. Almost dread to go to sleep in this account. I am getting worse and worse, and prison ditto.

In September Ransom was removed to a Marine hospital in Savannah, “very sick but by no means dead yet.” On July 10, in the worst of his extremity, he had written, “While I have no reason or desire to swear, I certainly cannot do this prison justice. It’s too stupendous an undertaking. Only those who are here will ever know what Andersonville is.”