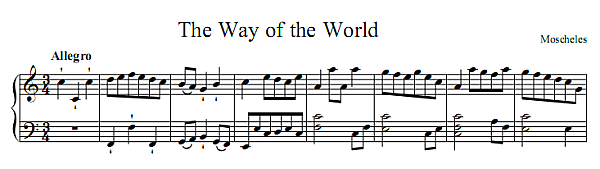

Ignaz Moscheles’ piano piece “The Way of the World” is invertible — the music reads the same upside down.

Here’s pianist Felix Noel playing it both ways, and here’s a printable score if you’d like to try it yourself.

See Both Sides Now.

Ignaz Moscheles’ piano piece “The Way of the World” is invertible — the music reads the same upside down.

Here’s pianist Felix Noel playing it both ways, and here’s a printable score if you’d like to try it yourself.

See Both Sides Now.

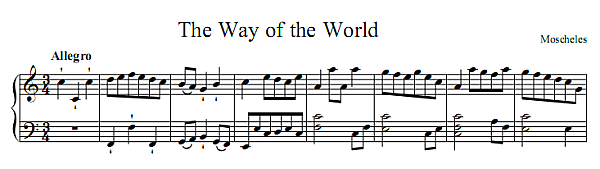

Why do mathematicians confuse Halloween with Christmas?

Because 31 Oct = 25 Dec.

(Thanks, Jan.)

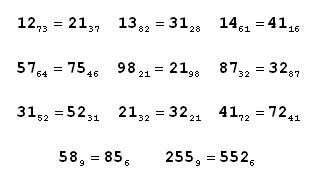

This “geographical love enigma” appeared on a German postcard in the early 20th century. Travel north to south through each successive country (green, red, purple, yellow), naming the geographical features you encounter in each, and you’ll produce the fourth song in Heinrich Heine’s Buch der Lieder:

Wenn ich in deine Augen seh,

So schwindet all mein Leid und Weh;

Doch wenn ich küsse deinen Mund,

So werd ich ganz und gar gesund.

Wenn ich mich lehn an deine Brust,

Kommt’s über mich wie Himmelslust;

Doch wenn du sprichst: “Ich liebe dich!”

So muss ich weinen bitterlich.

When I look into your eyes,

Then vanish all my sorrow and pain!

Ah, but when I kiss your mouth,

Then I will be wholly and completely healthy.

When I lean on your breast,

I am overcome with heavenly delight,

Ah, but when you say, “I love you!”

Then I must weep bitterly.

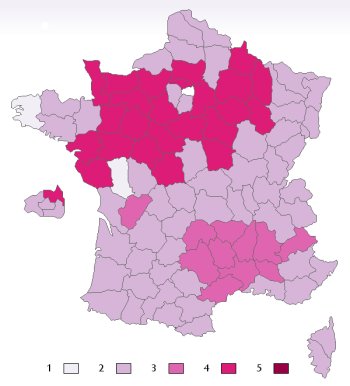

The French greet one another with kisses on the cheek, but the number of kisses varies with the département. In 2007 Gilles Debunne set up a website, Combien de bises?, on which his countrymen could record their local customs; to date, after more than 87,000 votes, the results range from 1 kiss in Finistère to 4 in Loire Atlantique.

“It’s a lot more subtle than I ever imagined,” Debunne told the Times. “Sometimes the number of kisses changes depending on whether you’re seeing friends or family or what generation you belong to.”

pernoctation

n. the act of staying up all night

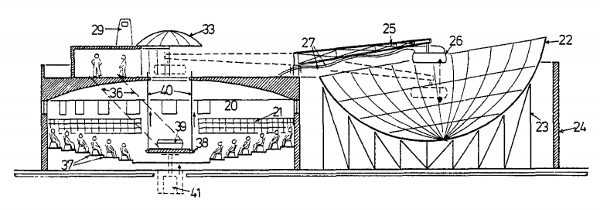

An ordinary cremation consumes valuable energy and consigns the body to flames, which has unpleasant connotations of hellfire and damnation. In 1983 Kenneth H. Gardner invented a greener, more uplifting alternative — the corpse is elevated through the roof and then cremated by concentrated solar energy.

A temperature of about 1,700° F. is required to provide incineration and a total of about 3,000,000 BTU’s is required to consume a corpse. Thus, at a supply rate of about 1,000,000 BTU/hour, cremation would take about three hours. A concave mirror-reflector bowl similar to the steam-producing Crosbyton hemisphere in Lubbock, Texas is considered a suitable collector. At 65 ft. diameter, a bowl of this type can produce approximately 1,000,000 BTU/Hr. under full sunshine conditions from mid-morning to mid-afternoon.

Gas burners are still available “for auxiliary use during inclement weather and/or when it is desired to expedite the cremation process.”

Puzzle maven David Singmaster presented this conundrum at the first Gathering for Gardner:

My daughter Jessica is 16 and very conscious of her age. Our neighbour Helen is just 8, and I teased Jessica by saying, ‘Seven years ago, you were 9 times as old as Helen; six years ago, you were 5 times her age; four years ago, you were 3 times her age; and now you are only twice her age. If you are not careful, soon you’ll be the same age!’

Jessica seemed a bit worried, and went off muttering. I saw her doing a lot of scribbling.

The next day, she said to me, ‘Dad, that’s just the limit! By the way, did you ever consider when I would be half as old as Helen?’ Now it was my turn to be worried, and I began muttering — ‘That can’t be, you’re always older than Helen.’

‘Don’t be so positive,’ said Jessica, as she stomped off to school.

Can you help me out?

He withheld the answer, but I think I see it.

In May 2009, California consumer Janine Sugawara sued PepsiCo for implying that crunchberries are a fruit. She claimed that she and other consumers had been misled both by the name of the cereal and by the image on the box of Cap’n Crunch “thrusting a spoonful of ‘Crunchberries’ at the prospective buyer.” The package suggests that the product contains real fruit, she said; had she known otherwise, she would not have bought it.

“While the challenged packaging contains the word ‘berries’ it does so only in conjunction with the descriptive term ‘crunch’,” wrote Judge Morrison England Jr., reflecting wearily upon the course his life had taken. “This Court is not aware of, nor has Plaintiff alleged the existence of, any actual fruit referred to as a ‘crunchberry.’ Furthermore, the ‘Crunchberries’ depicted on the [box] are round, crunchy, brightly-colored cereal balls, and the [box] clearly states both that the Product contains ‘sweetened corn & oat cereal’ and that the cereal is ‘enlarged to show texture.’ Thus, a reasonable consumer would not be deceived into believing that the Product in the instant case contained a fruit that does not exist.”

He dismissed the case and denied Sugawara the chance to amend her complaint. “The survival of the instant claim would require this Court to ignore all concepts of personal responsibility and common sense,” he wrote. “The Court has no intention of allowing that to happen.”

An S A now I mean 2 write

2 U sweet K T J,

The girl without a ∥,

The belle of U T K.

I 1 der if U got that 1

I wrote 2 U B 4

I sailed in the R K D A,

And sent by L N Moore.

My M T head will scarce contain

A calm I D A bright,

But A T miles from you I must

M{ this chance 2 write.

And first, should N E N V U,

B E Z, mind it not.

Should N E friendship show, be true:

They should not be forgot.

From virt U nev R D V 8;

Her influence B 9

Alike induces 10 dern S,

Or 40 tude D vine.

And if you cannot cut a —

Or cause an !

I hope U’ll put a .

2 1 ?

R U for an X ation 2,

My cous N ? — heart and ☞

He off R’s in a ¶

A § 2 of land.

He says he loves you 2 X S,

U R virtuous and Y’s,

In X L N C U X L

All others in his I’s.

This S A, until U I C,

I pray U 2 X Q’s,

And do not burn in F E G

My young and wayward muse.

Now fare U well, dear K T J,

I trust that U R true–

When this U C, then you can say,

An S A I O U.

— Charles Carroll Bombaugh, Gleanings for the Curious From the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1890

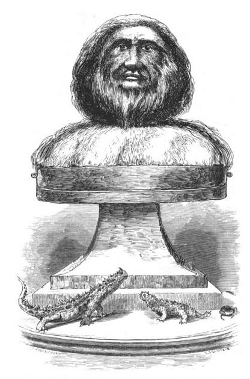

To demonstrate “the discovery which I had made of preparing specimens upon scientific principles,” eccentric naturalist Charles Waterton (1782-1865) created “The Nondescript,” a red howler monkey whose face he had manipulated into a semi-human cast.

“I have no wish whatever that the nondescript should pass for any other thing than that which the reader himself should wish it to pass for,” he wrote, rather elliptically. “Not considering myself pledged to tell its story, I leave it to the reader to say what it is, or what it is not.”

The specimen is preserved at the Wakefield Museum in West Yorkshire. Lost is a similar Waterton creation, “The English Reformation Zoologically Demonstrated,” a series of “portraits” of famous Protestants fashioned from preserved lizards and toads.

Such experiments could make Waterton seem unfeeling, but he was fundamentally more sympathetic with the wildlife of South America than the Georgian society to which he’d been born. He made this address to a sloth he surprised on the banks of the Essequibo in Guyana:

“Come, poor fellow. If thou hast got into a hobble to-day, thou shalt not suffer for it: I’ll take no advantage of thee in misfortune; the forest is large enough for both thee and me to rove in: go thy ways up above, and enjoy thyself in these endless wilds; it is more than probable thou wilt never have another interview with man. So fare thee well.”

(“I followed him with my eye till the intervening branches closed in betwixt us; and then I lost sight for ever of the two-toed Sloth. I was going to add, that I never saw a Sloth take to his heels in such earnest: but the expression will not do, for the Sloth has no heels.”)