A problem from Litton Problematical Recreations, which attributes it to Fermat circa 1635:

What is the remainder upon dividing 5999,999 by 7?

A problem from Litton Problematical Recreations, which attributes it to Fermat circa 1635:

What is the remainder upon dividing 5999,999 by 7?

“Wandering in a vast forest at night, I have only a faint light to guide me. A stranger appears and says to me: ‘My friend, you should blow out your candle in order to find your way more clearly.’ This stranger is a theologian.” — Diderot

Jenny kissed me when we met,

Jumping from the chair she sat in.

Time, you thief, who love to get

Sweets into your list, put that in.

Say I’m weary, say I’m sad;

Say that health and wealth have missed me;

Say I’m growing old, but add —

Jenny kissed me!

— Leigh Hunt

Jenny kissed me when we met.

She, adorned in silk and satin,

Told me, “That is all you get;

And as you leave, don’t let the cat in.”

Retrospection makes me glad:

Dread disease perhaps thus missed me.

God knows what I might have had

Had Jenny more than merely kissed me.

— Bruce Newling

I place four balls in a hat: a blue one, a white one, and two red ones. Now I draw two balls, look at them, and announce that at least one of them is red. What is the chance that the other is red?

“Lord Dawson was not a good doctor. King George V himself told me that he would never have died had he had another doctor.” — Margot Asquith, to the young Lord David Cecil

From an 1863 interview with blacksmith Solomon Bradley regarding the punishment of slaves in South Carolina:

Q. Can you speak of any particular cases of cruelty that you have seen?

A. Yes, sir; the most shocking thing that I have seen was on the plantation of Mr. Farrarby, on the line of the railroad. I went up to his house one morning from my work for drinking water, and heard a woman screaming awfully in the door-yard. On going up to the fence and looking over I saw a woman stretched out, face downwards, on the ground her hands and feet being fastened to stakes. Mr. Farrarby was standing over and striking her with a leather trace belonging to his carriage-harness. As he struck her the flesh of her back and legs was raised in welts and ridges by the force of the blows. Sometimes when the poor thing cried too loud from the pain Farrarby would kick her in the mouth. After he had exhausted himself whipping her he sent to his house for sealing wax and lighted candle and, melting the wax, dropped it upon the woman’s lacerated back. He then got a riding whip and, standing over the woman, picked off the hardened wax by switching at it. Mr. Farrarby’s grown daughters were looking at all this from a window of the house through the blinds. This punishment was so terrible that I was induced to ask what offence the woman had committed and was told by her fellow servants that her only crime was in burning the edges of the waffles that she had cooked for breakfast. The sight of this thing made me wild almost that day. I could not work right and I prayed the Lord to help my people out of their bondage. I felt I could not stand it much longer.

From John W. Blassingame, Slave Testimony, 1977.

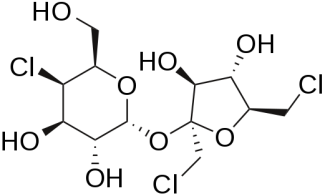

In 1976, Queen Elizabeth College chemist Leslie Hough asked graduate researcher Shashikant Phadnis to test a certain chlorinated sugar compound. Phadnis, whose English was imperfect, “thought I needed to taste it! … So I took a small quantity of the sample on a spatula and tasted it with the tip of my tongue.”

To his surprise, Phadnis found the compound intensely and pleasantly sweet. When he reported his discovery to Hough, “‘Are you crazy or what?’ he asked me. ‘How could you taste compounds without knowing anything about their toxicity?'” After some further cautious tasting, Hough dubbed the compound Serendipitose. It became the artificial sweetener Splenda.

“Later on, Les even had a cup of coffee sweetened with a few particles of Serendipitose. When I reminded him that it could be toxic (as it contained a high proportion of chlorine), he simply said, ‘Oh, forget it, we’ll survive!'”

Letter to the Times, Oct. 18, 1968:

Sir,

This afternoon I caught the 15:05 train from the recently modernized Euston Station.

According to the new electronic departure indicator, its destination was Rugby; according to the ticket collector and a notice on the platform it was Coventry; according to the destination blind on the train it was Wolverhampton. I got off at Watford to hear the station announcer declare it was Wolverhampton and walked home to look it up in my copy of the timetable and discover it was Birmingham.

Perhaps now that their modernization scheme is complete British Rail’s executives will have enough time to decide where their trains are going to?

Yours faithfully,

Richard Harvey

Related: NATIONAL RAIL TIMETABLES is an anagram of ALL TRAINS AIM TO BE LATE IN.

On Sept. 21, 1956, Navy pilot Tom Attridge put his supersonic F11F Tiger into a shallow dive and test-fired two bursts from its 20mm cannon. Unfortunately, the jet was traveling so fast that it overtook its own rounds. One struck the engine, which failed on the way back to the airfield. Attridge crash-landed, losing a wing and a stabilizer but getting away safely. His Tiger had become the first jet aircraft to shoot itself down.

A puzzle sent to me by a Caltech grad student: A man is walking his dog on the beach. Each time he blows a whistle, the dog doubles its speed. If the dog starts at 2 meters per second, how many whistles does it hear? Answer: Fifteen — when the dog exceeds the speed of sound, it catches up with the earlier whistles.

(Thanks, John and Srivatsan.)