Motto heartening, inspiring,

Framed above my pretty desk,

Never Shelley, Keats, or Byring

Penned a phrase so picturesque!

But in me no inspiration

Rides my low and prosy brow —

All I think of is vacation

When I see that lucubration:

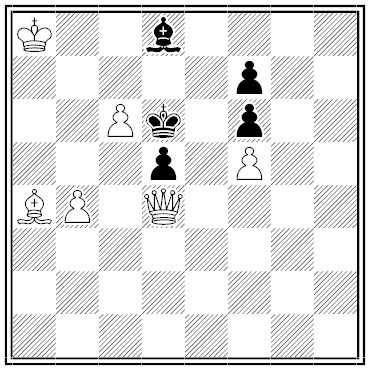

![]()

When I see another sentence

Framed upon a brother’s wall,

Resolution and repentance

Do not flood o’er me at all

As I read that nugatory

Counsel written years ago,

Only when one comes to borry

Do I heed that ancient story:

![]()

Mottoes flat and mottoes silly,

Proverbs void of point or wit,

“KEEP A-PLUGGIN’ WHEN IT’S HILLY!”

“LIFE’S A TIGER: CONQUER IT!”

Office mottoes make me weary

And of all the bromide bunch

There is only one I seri-

Ously like, and that’s the cheery:

![]()

— Franklin Pierce Adams, Tobogganning on Parnassus, 1913