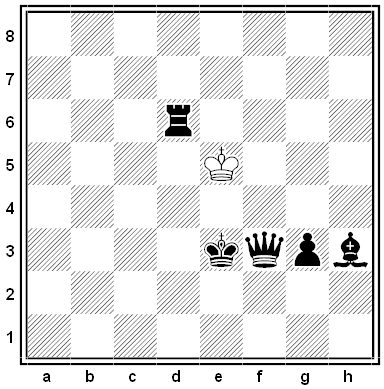

A logic problem in the shape of a chess puzzle, by Éric Angelini. White has just moved. What was his move?

A logic problem in the shape of a chess puzzle, by Éric Angelini. White has just moved. What was his move?

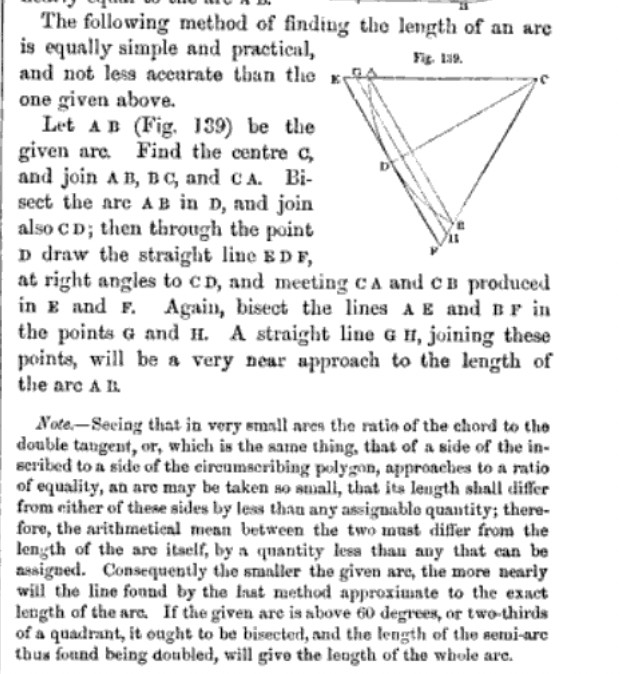

Peter Nicholson’s Carpenter’s New Guide of 1803 contains an interesting technique:

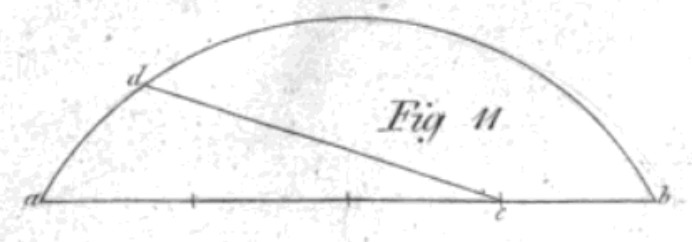

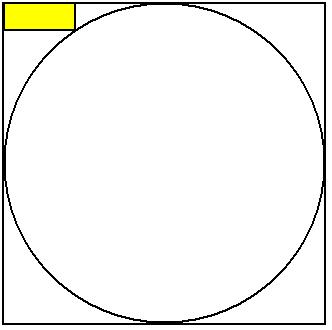

To find a right line equal to any given Arch of a Circle. Divide the chord ab into four equal parts, set one part bc on the arch from a to d, and draw dc which will be nearly equal to half the arch.

Apparently this was an item of carpentry lore in 1803. In the figure above, if arc ad = bc, then cd is approximately half of arc length ab.

Nicholson warns that this works best for relatively short arcs: “This method should not be used above a quarter of a circle, so that if you would find the circumference of a whole circle by this method, the fourth part must only be used, which will give one eighth part of the whole exceedingly near.”

But with that proviso it works pretty well — in 1981 University of Essex mathematician Ian Cook found that for arcs up to a quadrant of a circle, the results show a maximum percentage error of 0.6 percent, “which I suppose can be said to be ‘exceedingly near.'” He adds, “[I]t would be of interest to know who discovered this construction.”

(Ian Cook, “Geometry for a Carpenter in 1800,” Mathematical Gazette 65:433 [October 1981], 193-195.)

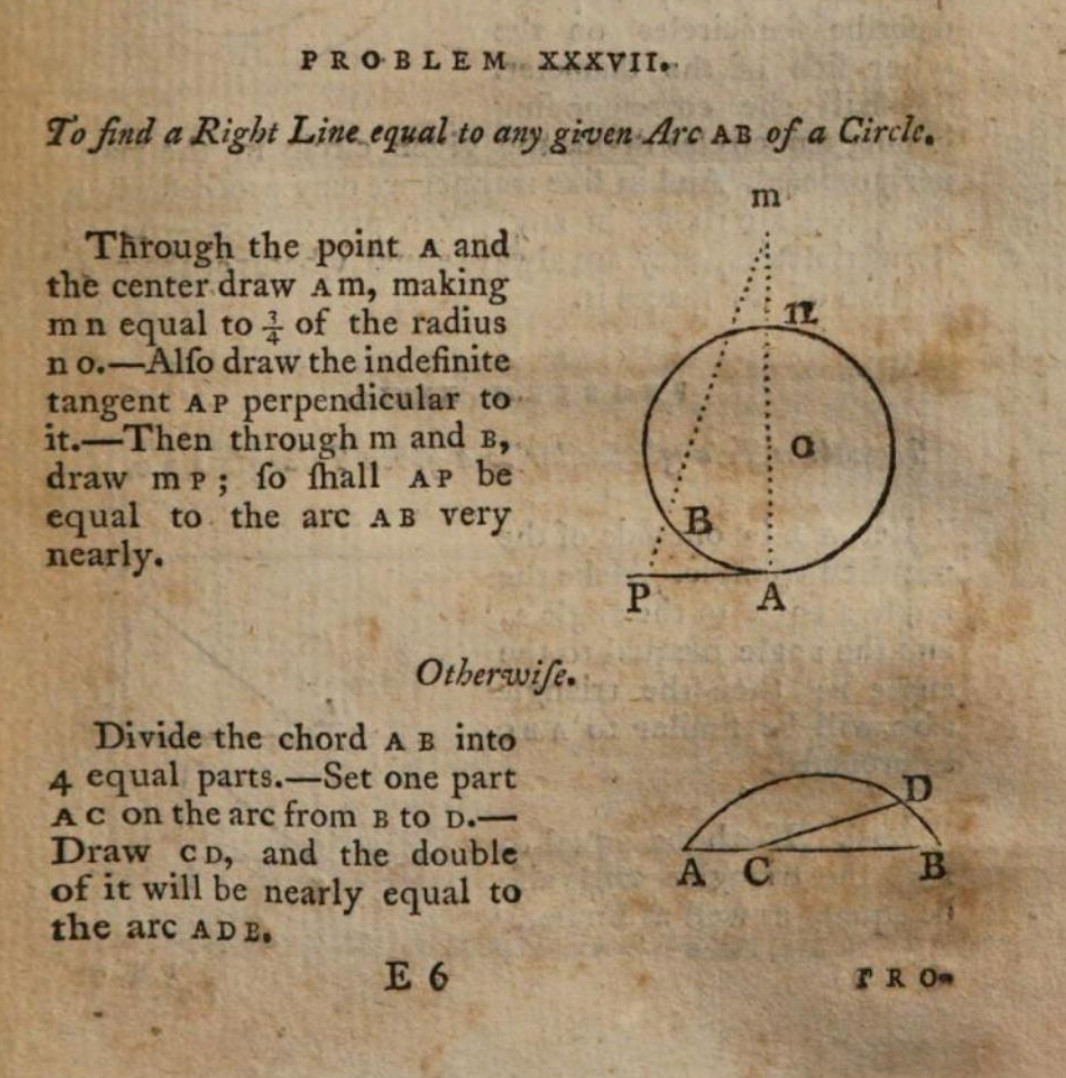

02/11/2025 UPDATE: Reader Edward White has found an earlier source, Charles Hutton’s The Compendious Measurer, published in 1786. Hutton gives two methods: The first finds the length directly, and the second is the method given in the Carpenter’s New Guide:

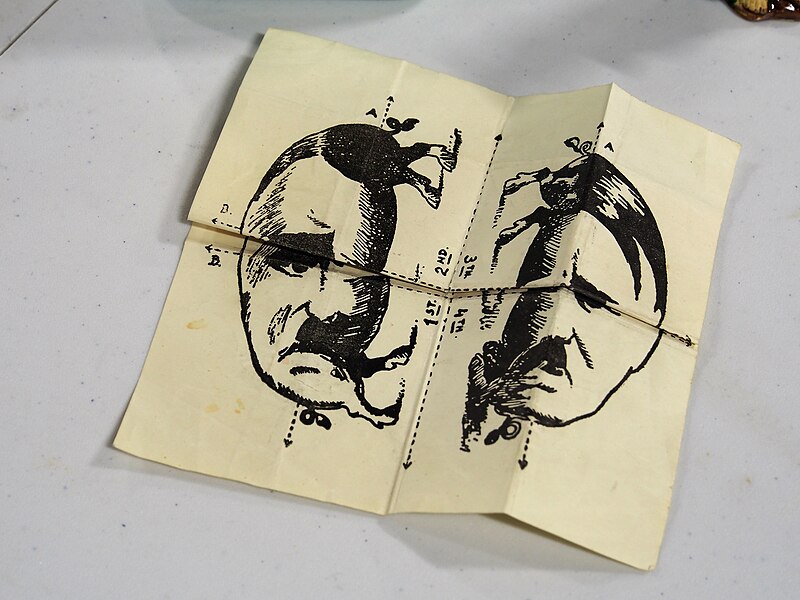

Edward discovered an alternate method of finding the length of an arc in The Carpenter’s and Joiner’s Assistant, 1869:

(Thanks, Edward.)

An 1897 article on curious wills in the Strand describes this 1813 will by the Rev. Hugh Worthington of Highbury Place, Islington. One side reads:

Northampton Square, June 16th, 1813. I, Hugh Worthington, give and bequeath to my dear Eliza Price, who is my adopted child, all I do or may possess, real and personal, to be at her sole and entire disposal; and I do appoint William Kent, Esq., of London Wall, my respected friend, with the said Eliza Price to execute this my last will and testament. — HUGH WORTHINGTON.

The other reads:

Most dearly beloved, my Eliza. Very small as this letter is, it contains the copy of my very last will. I have put it with your letters, that it may be sure to fall into your hands. Should accident or any other cause destroy the original, I have taken pains to write this very clearly, that you may read it easily. I do know you will perfect yourself in shorthand for my sake. Tomorrow we go for Worthing, I most likely never to return. I hope to write a few lines to express the best wishes, and prayers, and hopes of thy true, HUGH WORTHINGTON.

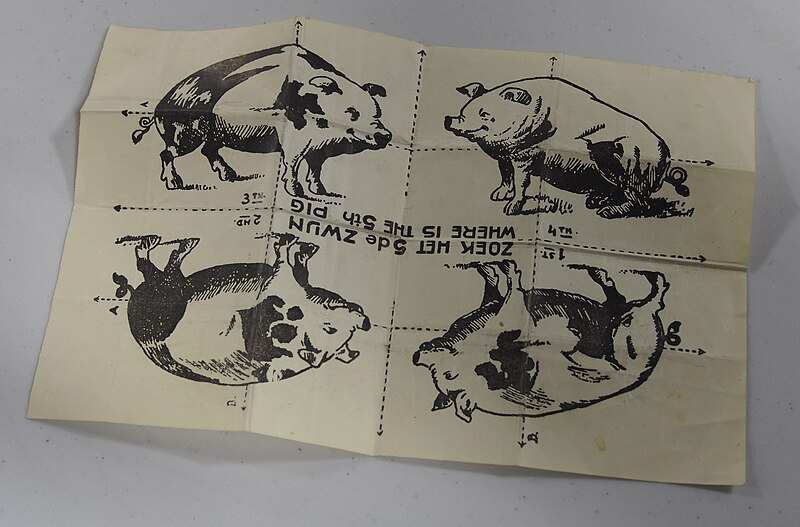

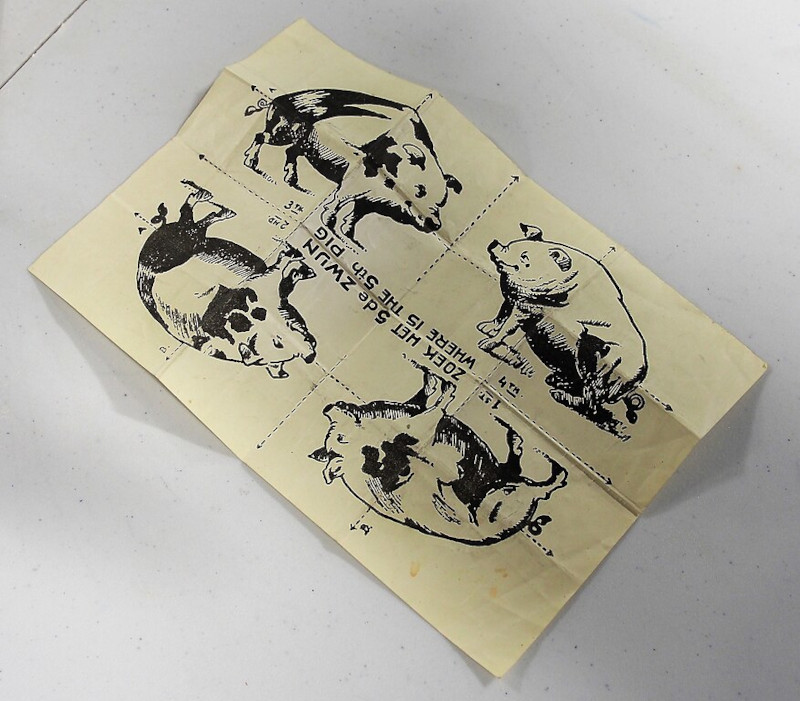

Just found this on Wikimedia Commons — “Where Is the Fifth Pig?”, an anonymous puzzle created in occupied Holland in 1940:

A circle is inscribed in a square, with a rectangle drawn from a corner of the square to a point on the circle, as shown. If this rectangle measures 6 inches by 12 inches, what’s the radius of the circle?

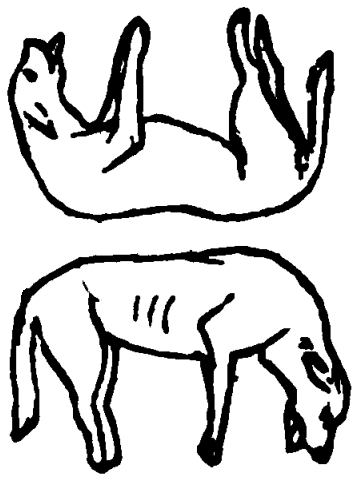

“The dogs are, by placing two lines upon them, to be suddenly aroused to life and made to run. Query, How and where should these lines be placed, and what should be the forms of them?”

John Grant McLoughlin offered this problem in Crux Mathematicorum in April 2008:

Every four-digit numerical palindrome (e.g., 2772) is a multiple of 11. Why is this?

The River Welland used to split into two channels in the heart of Crowland, Lincolnshire, and in 1360 the townspeople arranged to bridge it with this unique triple arch, which elegantly spanned the streams at the point of their divergence, allowing pedestrians to reach any of the three shores by a single structure. The alternative would have been to build three separate bridges.

The rivers were re-routed in the 1600s, so now the bridge stands in the center of town as a monument to the ingenuity of its inhabitants. It’s known as Trinity Bridge.

From the ArtefactPorn subreddit.

An intriguing photo caption from A Mind at Play, Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman’s 2017 biography of AI pioneer Claude Shannon:

Shannon set four goals for artificial intelligence to achieve by 2001: a chess-playing program that was crowned world champion, a poetry program that had a piece accepted by the New Yorker, a mathematical program that proved the elusive Riemann hypothesis, and, ‘most important,’ a stock-picking program that outperformed the prime rate by 50 percent. ‘These goals,’ he said only half-jokingly, ‘could mark the beginning of a phase-out of the stupid, entropy-increasing, and militant human race in favor of a more logical, energy conserving, and friendly species — the computer.’

Shannon wrote that in 1984. He died in 2001.