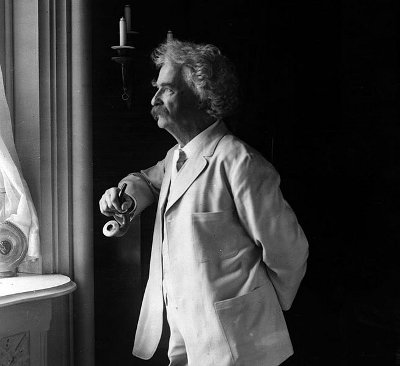

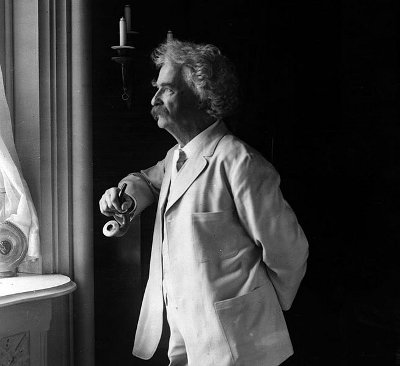

“The average American loves his family. If he has any love left over for some other person, he generally selects Mark Twain.” — Thomas Edison

“The average American loves his family. If he has any love left over for some other person, he generally selects Mark Twain.” — Thomas Edison

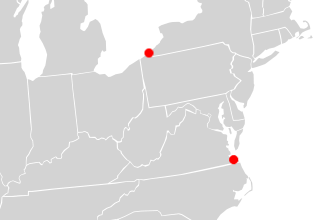

North East, Pennsylvania, is in northwest Pennsylvania.

Northwest, Virginia, is in southeast Virginia.

AM IN MARKET HARBOROUGH, G.K. Chesterton once telegraphed his wife. WHERE OUGHT I TO BE?

The 10-member Vienna Vegetable Orchestra plays instruments created entirely from fresh vegetables, including the carrot recorder, the pumpkin tympanum, the zucchini trumpet, and the bean maraca. These must be fashioned anew before each concert, because the old instruments are made into soup.

The Thai Elephant Orchestra, created by American expatriate Richard Lair and Columbia neurologist David Sulzer, improvise on drums, gongs, harmonicas, and sawmill blades. To date they’ve released three CDs.

Sulzer referred to one 7-year-old member as “the Fritz Kreisler of elephants.” “I put one bad note in the middle of her xylophone,” he told the New York Times in 2000. “She avoided playing that note — until one day she started playing it and wouldn’t stop. Had she discovered dissonance, and discovered that she liked it?”

“Just as there are a lot things they don’t understand about our music, I am sure there are things we will never understand about theirs.”

A curious case has recently been decided in England. A Mr. and Mrs. Hambling were both killed by a falling building. The husband was taken from the ruins quite dead, while the body of his wife was warm. The question was raised whether it could be safely presumed that the wife survived her husband, as this would cause a variation in the distribution of the property. The court decided against the supposition.

— Ballou’s Dollar Monthly Magazine, June 1859

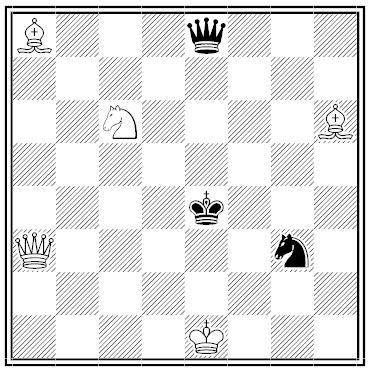

The British Chess Magazine reprinted this “amusing old timer” in 1892. “We suspect that the amusement will be caused by the rapidity of solving it, and the prettiness and surprise of the mating position.” White to mate in two moves.

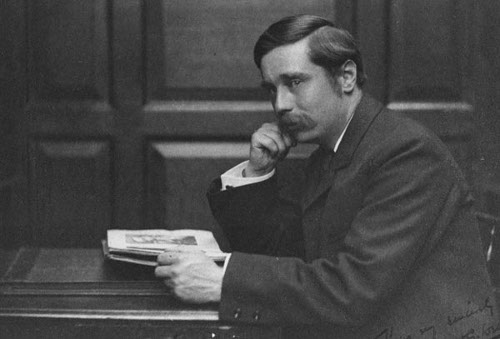

Mr. H.G. Wells

Was composed of cells.

He thought the human race

Was a perfect disgrace.

So wrote Edmund Clerihew Bentley in demonstrating the whimsical biographical verse that he invented. “I never heard who started the practice of referring to this literary form — if that is the word — as a Clerihew,” he wrote, “but it began early, and the name stuck.”

That’s as it should be: In a 1981 collection, Gavin Ewart wrote, “Nobody much except Bentley has ever written really good clerihews.” Samples:

“The moustache of Adolf Hitler

Could hardly be littler,”

Was the thought that kept recurring

To Field-Marshal Goering.

It is curious that Handel

Should always have used a candle.

Men of his stamp

Generally use a lamp.

Although Machiavelli

Was extremely fond of jelly,

He stuck religiously to mince

While he was writing The Prince.

The meaning of the poet Gay

Was always as clear as day,

While that of the poet Blake

Was often practically opaque.

A man in the position

Of the emperor Domitian

Ought to have thought twice

About being a Monster of Vice.

Edgar Allan Poe

Was passionately fond of roe.

He always like to chew some

When writing anything gruesome.

The great Duke of Wellington

Reduced himself to a skellington.

He reached seven stone two,

And then — Waterloo!

scroop

n. the rustle of silk

In the early 1970s, AI researcher James Meehan tried to teach a computer to retell Aesop’s fables. This was not always successful:

Once upon a time there was a dishonest fox and a vain crow. One day the crow was sitting in his tree, holding a piece of cheese in his mouth. He noticed that he was holding the piece of cheese. He became hungry, and swallowed the cheese. The fox walked over to the crow. The end.

Henry Ant was thirsty. He walked over to the river bank where his good friend Bill Bird was sitting. Henry slipped and fell in the river. He was unable to call for help. He drowned.

One day Henry Crow sat in his tree, holding a piece of cheese in his mouth, when up came Bill Fox. Bill saw the cheese and was hungry. He said, ‘Henry, I like your singing very much. Won’t you please sing for me?’ Henry, flattered by this compliment, began to sing. The cheese fell to the ground. Bill Fox saw the cheese on the ground and was very hungry. He became ill. Henry Crow saw the cheese on the ground, and he became hungry, but he knew that he owned the cheese. He felt pretty honest with himself, so he decided not to trick himself into giving up the cheese. He wasn’t trying to deceive himself, either, nor did he feel competitive with himself, but he remembered that he was also in a position of dominance over himself, so he refused to give himself the cheese. He couldn’t think of a good reason why he should give himself the cheese, so he offered to bring himself a worm if he’d give himself the cheese. That sounded okay, but he didn’t know where any worms were. So he said to himself, ‘Henry, do you know where any worms are?’ But of course, he didn’t, so he …

“The program eventually ran aground for other reasons,” Meehan writes. “I was surprised it got as far as it did.”

(From Meehan’s The Metanovel: Writing Stories by Computer, 1980.)

John Train’s Most Remarkable Names reports that Chazy Lake, N.Y., has a resident named Constant Agony.

In Stories on Stone, Charles L. Wallis notes that a tombstone in Hood River, Ore., reads:

In The American Language, H.L. Mencken mentions an Indian chief in the northwestern U.S. named Unable-to-Fornicate. “And I once knew a Siletz who insisted with firm complacency that his name, no matter what anybody thought it, was Holy Catfish.”

“I have only made this letter rather long because I have not had time to make it shorter.” — Pascal

“It usually takes more than three weeks to prepare a good impromptu speech.” — Mark Twain

“If you want me to talk for ten minutes, I’ll come next week. If you want me to talk for an hour I’ll come tonight.” — Woodrow Wilson

Also:

Harold Macmillan: “What are you doing, prime minister?”

Winston Churchill: “Rehearsing my impromptu witticisms.”