opsigamy

n. marriage at an advanced age

benedick

n. a newly married man

shunamitism

n. rejuvenation of an old man by a young woman

opsigamy

n. marriage at an advanced age

benedick

n. a newly married man

shunamitism

n. rejuvenation of an old man by a young woman

An admirer once asked Winston Churchill, “Doesn’t it thrill you to know that every time you make a speech the hall is packed to overflowing?”

Churchill replied, “It is quite flattering, but whenever I feel this way I always remember that if instead of making a political speech I was being hanged, the crowd would be twice as big.”

Morris Garstenfeld repeatedly greeted a Brooklyn neighbor “by placing the end of his thumb against the tip of his nose, at the same time extending and wiggling the fingers of his hand.” Is this disorderly conduct? That question fell to Kings County Judge J. Roy in 1915.

“What meaning is intended to be conveyed by the above-described pantomime?” Roy mused. “Is it a friendly or an unfriendly action; a compliment or an insult? Is it a direct invitation to fight, or is it likely to provoke a fight?”

He declared that the gesture is well known among boys, and that it should be abandoned by men. In Garstenfeld’s case, the “nasal and digit drama” tended “to show a design to engender strife,” and the fact that Garstenfeld had done it repeatedly showed that he meant to annoy his victim “to the limit of patient endurance.” He affirmed Garstenfeld’s conviction.

A riddle by Jonathan Swift:

We are little airy creatures,

All of different voice and features:

One of us in glass is set,

One of us you’ll find in jet,

T’other you may see in tin,

And the fourth a box within;

If the fifth you should pursue,

It can never fly from you.

What are we?

In October 1864, Indiana farmer John VanNuys received a letter informing him that his son had been killed in the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm in Virginia. He had been shot in the throat while retreating from a line of Confederate rifle pits. “Within twenty minutes our forces rallied and took the ground,” wrote the quartermaster, “but while the rebels held the ground, they had stripped your son of everything except shirt and drawers.”

A few days later VanNuys received an envelope postmarked “Old Point Comfort, Oct. 10.” Inside was a note in his son’s handwriting:

This testament belongs to Captain S.W. VanNuys, Acting Ass’t. Adj’t. General 3d Brigade, 3d Div., 18th Army Corps. Should I die upon the field of battle, for the sake of a loving mother and sister, inform my father, John H. VanNuys, Franklin, Indiana, of the fact.

Below this someone had written:

Mr. John H. Vanings: It is my faithful duty to inform you that your son was killed on the 29th of the last month near Chaffins farm, Va. I have his testament. I will send it if you wish it. From your enemy, one of the worst rebels you ever seen.

The sender had signed it only “L.B.F.” His identity is unknown.

During the oil boom of 1919, Wichita Falls, Texas, was desperate for office space, so investors jumped at developer J.D. McMahon’s offer to build a 480″ high rise downtown.

When the building turned out to be four stories tall, they double-checked the blueprints. McMahon had promised a building 480 inches tall, not 480 feet. And that’s what he’d delivered.

By that time he had decamped with the money.

In 1921 Charles Purdy worried that modern foods require too little chewing, resulting in “decayed teeth, undeveloped jaws, and various other complications due solely to the lack of exercise attendant on proper mastication.”

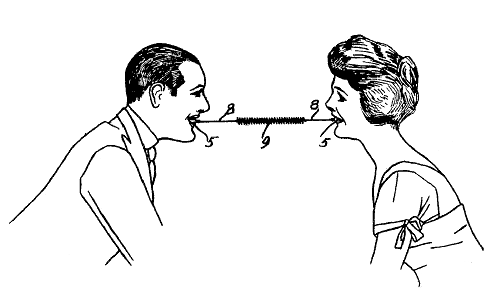

The answer, he decided, was a bite plate that can be attached to the wall by a spring. “By movements of the head, the device will receive a series of short jerks or impulses which will be transmitted to the teeth in order to produce a strain thereon, which strain serves to give the several organs of the mouth and head a proper exercise to maintain the necessary circulation therein.”

When used in tandem, as shown, this has all the makings of a romantic candlelight interlude as the exercisers “pull in opposite directions similar to the so-called ‘tug-of-war.'” What did this sound like?

When Long Island filmmaker Ellen Cooperman divorced her husband in 1975, she changed her last name to Cooperperson because it “more properly reflects [my] sense of human equality than does the name Cooperman.”

State Supreme Court Justice John Scileppi refused to ratify the change, saying that it “would have serious and undesirable repercussions, perhaps throughout the entire country.” He cited “virtually endless and increasingly inane” possibilities: A person named “Jackson” might seek to become “Jackchild,” a “Manning” might prefer “Peopling,” or a woman named “Carmen” might want to be “Carperson.” “This would truly be in the realm of nonsense,” he said.

Undaunted, she appealed Scileppi’s decision and won in 1978. She’s still using Cooperperson today.

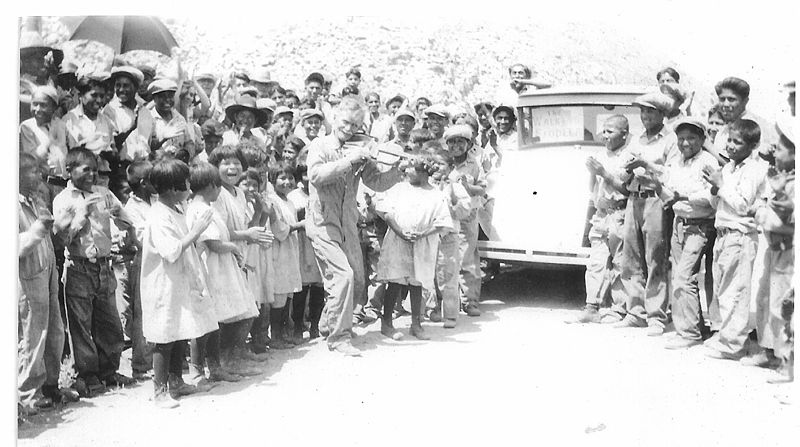

Otto Funk left New York City on June 28, 1928. He arrived in San Francisco on July 25, 1929. In the interval he walked 4,165 miles, fiddling every step of the way.

Oh, and defying death. “While traveling through Arizona Funk was struck by a rattlesnake,” reported the Los Angeles Times. “Unperturbed, the aged fiddler slew the snake, snipped off the rattles as souvenirs, cut open the wound and sucked out the blood and poison. He continued walking until he came to a doctor’s office.”

“I have seen God’s country, every foot of it that I walked over,” Funk said afterward. “You can’t see it right from a car or a train. Sole leather express is the only way.”

A German-born resident of Portland, Oregon named Otto Hell was permitted by a local judge to take the name Hall when he pointed out how his neighbors and associates took pleasure in calling him by his surname and the initial of his given name. Another Otto Hell was an optometrist who complained that persons in need of glasses were always being told to ‘go to Hell and see.’

— Robert M. Rennick, “Obscene Names and Naming in Folk Tradition,” in Names and Their Varieties, 1986