fIVe + sIX + seVen

5 + 6 + 7 = 18

IV + IX + V = 18

These are the only three consecutive numbers whose sum equals that of the Roman numerals embedded in their names.

fIVe + sIX + seVen

5 + 6 + 7 = 18

IV + IX + V = 18

These are the only three consecutive numbers whose sum equals that of the Roman numerals embedded in their names.

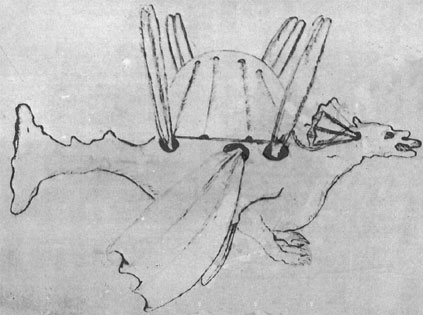

In 1647, Venetian inventor Tito Livio Burattini built a flying machine that could carry a cat. Reportedly the vessel had four pairs of wings and was driven by cords pulled by hand; it “remained airborne as long as a man kept the feathers and wheels in motion by the way of a string.” One observer wrote, “if the cat had the understanding to do that — its strength would be sufficient for this — it would keep itself in the air.”

This 4-foot “Dragon Volant” was only a prototype; Burattini hoped to produce a finished version that could carry a man. By May 1648 he’d brought out an improved model, and German polymath Johann Joachim Becher even mentions a report that the aircraft eventually rose into the air with three people aboard, including the inventor, who “wanted to fly from Warsaw to Constantinople inside 12 hours.” But “as there were always some shortcomings, perfection was never achieved,” and it appears the project ended there.

(Jerzy B. Cynk, Polish Aircraft, 1893-1939, 1971.)

A problem from the October 1964 issue of Eureka, the journal of the Cambridge University Mathematical Society:

My friend tosses two coins and covers them with his hand. ‘Is there at least one “tail”?’ I ask. He affirms this (a).

Just then he accidentally knocks one of them to the floor (b). On finding the dropped coin under the table, we discover it to be a ‘tail’ (c).

‘That is all right,’ he says, ‘because it was a “tail” to start with.’ (d).

At each point (a), (b), (c) and (d) of this episode I calculated what, to the best of my knowledge, was the probability that both coins showed ‘tails’ at the time. What were these probabilities?

The sea urchin Coelopleurus exquisitus was discovered on eBay. Marine biologist Simon Coppard was directed to a listing on the site in 2004 and realized that the species had not previously been described. When it was properly named and introduced in Zootaxa two years later, the value of specimens on eBay shot up from $8 to $138.

In 2008 a fossilized aphid on eBay was similarly found to be unidentified. Eventually it was named Mindarus harringtoni, after the buyer.

“A conference is a gathering of important people who singly can do nothing, but together can decide that nothing can be done.” — Fred Allen

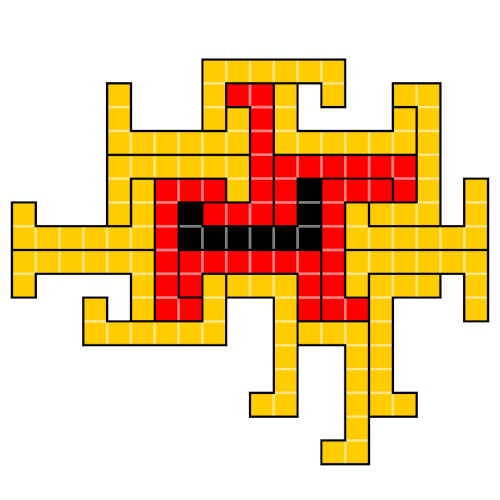

The dark polyomino at the center of this figure, devised by Craig S. Kaplan, has an unusual property: It can be surrounded snugly with copies of itself, leaving no overlaps or gaps. In this case, the “corona” (red) can be surrounded with a second corona (amber), itself also composed of copies of the initial shape. But that’s as far as we can get — there’s no way to create a third corona using the same shape.

That gives the initial shape a “Heesch number” of 2 — the designation is named for German geometer Heinrich Heesch, who had proposed this line of study in 1968.

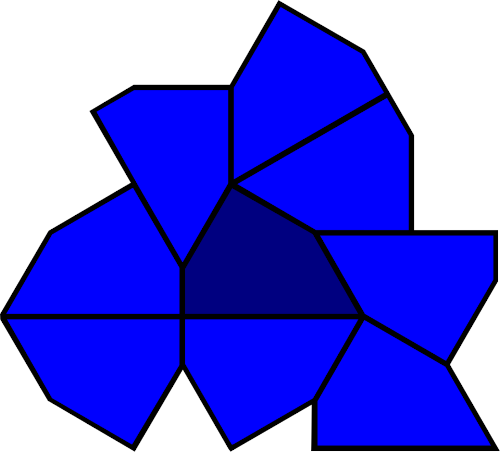

Shapes needn’t be polyominos: Heesch himself devised the example below, the union of a square, an equilateral triangle, and a 30-60-90 triangle:

It earns a Heesch number of 1, as it can bear only the single corona shown.

Can all positive integers be Heesch numbers? That’s unknown. The Heesch number of the square is infinite, and that of the circle is zero. The highest finite number reached so far is 6.

Excerpts from Mark Twain’s boyhood journal:

Monday — Got up, washed, went to bed.

Tuesday — Got up, washed, went to bed.

Wednesday — Got up, washed, went to bed.

Thursday — Got up, washed, went to bed.

Friday — Got up, washed, went to bed.

Next Friday — Got up, washed, went to bed.

Friday fortnight — Got up, washed, went to bed.

Following month — Got up, washed, went to bed.

“I stopped, then, discouraged. Startling events appeared to be too rare, in my career, to render a diary necessary.”

(From The Innocents Abroad.)

Much of the success of the administrator in carrying out a program depends upon how far it is his sole object overshadowing everything else, or how far he is thinking of himself; for this last is an obstruction that has caused many a good man to stumble and a good cause to fall. The two aims are inconsistent, often enough for us to state as a general rule that one cannot both do things and get the credit for them.

— A. Lawrence Lowell, What a University President Has Learned, 1938

The index for Hugh Vickers’ 1985 book Great Operatic Disasters contains an entry for which no page numbers are given:

Incompetence — better not specified