“Of all the illusions that beset mankind none is quite so curious as that tendency to suppose that we are mentally and morally superior to those who differ from us in opinion.” — Elbert Hubbard

Author: Greg Ross

The Crossing

A family of four has to cross a river. The father and mother each weigh 150 pounds, and each of the two sons weighs 75 pounds. Unfortunately, the boat will carry only 150 pounds maximum. How can they get across?

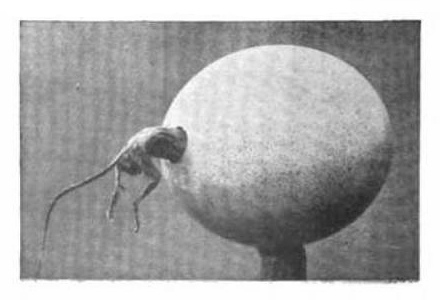

“An Egg as a Rat-Trap”

I send you a photograph showing the untimely fate which befell a too inquisitive rat. It had managed to force its way into an ostrich egg, but then found that getting out was quite another matter, and so perished in the miserable manner shown in the following picture, which was sent to me by Mr. William Fisher, Mahalapye, B. Bechuanaland. — Miss G. Gardiner, 78, Guilford Street, W.C.

— Strand, July 1908

See “A Man Drowned by a Crab” and “A Rat Caught by an Oyster.”

Short Subject

Here is a short poem which is complete without any exercise of the imagination. The rhymes need no precedent clauses; they are heads and tails at once. In their simple way they tell the sad story of a common domestic tragedy:

— William Shepard Walsh, Handy-Book of Literary Curiosities, 1892

Rimshot

A guy goes into a bank and says he wants to borrow $200 for six months. The loan officer asks him what collateral he has, and he says, “I have a Rolls Royce. Here are the keys — you can keep it until the loan is paid off.”

Six months later the guy comes back and pays off the $200 loan, plus $10 interest. The loan officer says, “Here are the keys. If you don’t mind my asking, why would a man who owns a Rolls Royce need to borrow $200?”

The guy says, “I had to go overseas for six months. Where else could I store a Rolls Royce for $10?”

Perspective

“How are you going to teach logic in a world where everybody talks about the sun setting, when it’s really the horizon rising?” — Cal Craig, quoted in Howard Eves, Mathematical Circles Revisited, 1971

In a Word

misopedia

n. dislike of children

Run Toppers

Let’s play a game. We’ll each name three consecutive outcomes of a coin toss (for example, tails-heads-heads, or THH). Then we’ll flip a coin repeatedly until one of our chosen runs appears. That player wins.

Is there any strategy you can take to improve your chance of beating me? Strangely, there is. When I’ve named my triplet (say, HTH), take the complement of the center symbol and add it to the beginning, and then discard the last symbol (here yielding HHT). This new triplet will be more likely to appear than mine.

The remarkable thing is that this always works. No matter what triplet I pick, this method will always produce a triplet that is more likely to appear than mine. It was discovered by Barry Wolk of the University of Manitoba, building on a discovery by Walter Penney.

“French for Americans”

Phrases most in demand by American visitors to Paris, compiled by Robert Benchley:

Pronunciation:

a = ong

e = ong

i = ong

o = ong

u = ong

Haven’t you got any griddle-cakes?

N’avez-vous pas des griddle-cakes?

What kind of a dump is this, anyhow?

Quelle espèce de dump is this, anyhow?

Do you call that coffee?

Appelez-vous cela coffee?

Where can I get a copy of the N.Y. Times?

Où est le N.Y. Times?

What’s the matter? Don’t you understand English?

What’s the matter? Don’t you understand English?

Of all the godam countries I ever saw.

De tous les pays godams que j’ai vu.

I haven’t seen a good-looking woman yet.

Je n’ai pas vu une belle femme jusqu’à présent.

Here is where we used to come when I was here during the War.

Ici est où nous used to come quand j’étais ici pendant la guerre.

Say, this is real beer all right!

Say, ceci est de la bière vrai!

Oh boy!

O boy!

Two weeks from tomorrow we sail for home.

Deux semaines from tomorrow nous sail for home.

Then when we land I’ll go straight to Childs and get a cup of coffee and a glass of ice-water.

Sogleich wir zu hause sind, geh ich zum Childs und eine tasse kaffee und ein glass eiswasser kaufen.

“Word you will have little use for”:

Vernisser — to varnish, glaze.

Nuque — nape (of the neck).

Egriser — to grind diamonds.

Dromer — to make one’s neck stiff from working at a sewing machine.

Rossignol — nightingale, picklock.

Ganache — lower jaw of a horse.

Serin — canary bird.

Pardon — I beg your pardon.

The Airy Box

It’s said that British Astronomer Royal G.B. Airy once discovered an empty box at the Greenwich Observatory in London.

He wrote EMPTY BOX on a piece of paper and put it inside.

“Attached to the outside, such a label is true,” write Gary Hayden and Michael Picard in This Book Does Not Exist. “Placed inside the box, it makes itself false. Alternatively, suppose the label says: ‘The box this label is inside is empty.’ Outside of any box, the subject of this sentence fails to refer — there is no box inside which the label is located. However, once inside an otherwise empty box, the sentence becomes false.”