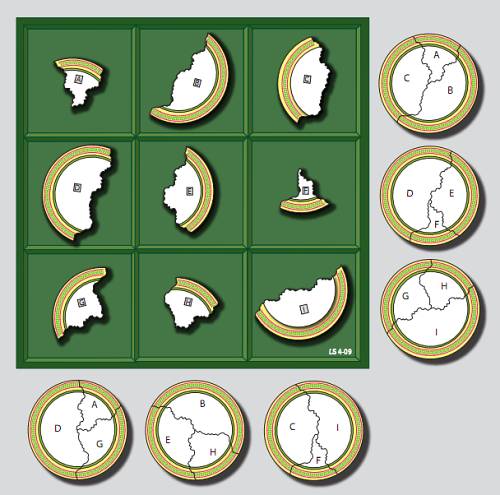

From Lee Sallows, a geometric magic square:

The shards in each row and column produce a complete plate.

So do the diagonals!

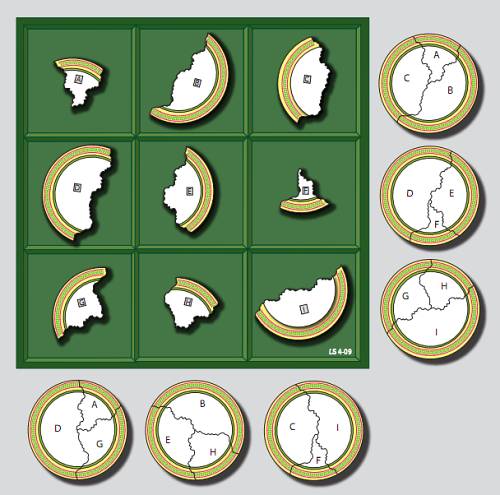

From Lee Sallows, a geometric magic square:

The shards in each row and column produce a complete plate.

So do the diagonals!

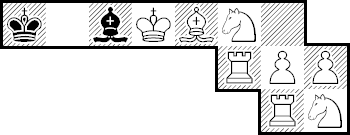

By T.R. Dowson. White to mate in 21 moves:

It’s not as hard as it sounds, though it’s a bit like a square dance in a submarine.

‘Well, then, good fellow, holy father, or whatever thou art,’ quoth Robin, ‘I would know whether this same Friar is to be found upon this side of the river or the other.’

‘Truly, the river hath no side but the other,’ said the Friar.

‘How dost thou prove that?’ asked Robin.

‘Why, thus,’ said the Friar, noting the points upon his fingers. ‘The other side of the river is the other, thou grantest?’

‘Yea, truly.’

‘Yet the other side is but one side, thou dost mark?’

‘No man could gainsay that,’ said Robin.

‘Then if the other side is one side, this side is the other side. But the other side is the other side, therefore both sides of the river are the other side. Q.E.D.’

”Tis well and pleasantly argued,’ quoth Robin, ‘yet I am still in the dark as to whether this same Curtal Friar is upon the side of the river on which we stand or upon the side of the river on which we do not stand.’

‘That,’ quoth the Friar, ‘is a practical question upon which the cunning rules appertaining to logic touch not. I do advise thee to find that out by the aid of thine own five senses; sight, feeling, and what not.’

— Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, 1883

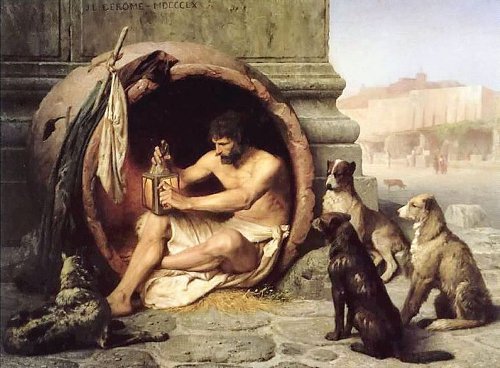

Aristippus passed Diogenes as he was washing lentils.

He said, “If you could but learn to flatter the king, you would not have to live on lentils.”

Diogenes said, “And if you could learn to live on lentils, you would not have to flatter the king.”

If materialism is true, all our thoughts are produced by purely material antecedents. These are quite blind, and are just as likely to produce falsehood as truth. We thus have no reason for believing any of our conclusions — including the truth of materialism, which is therefore a self-contradictory hypothesis.

— J.E. McTaggart, Philosophical Studies, 1934

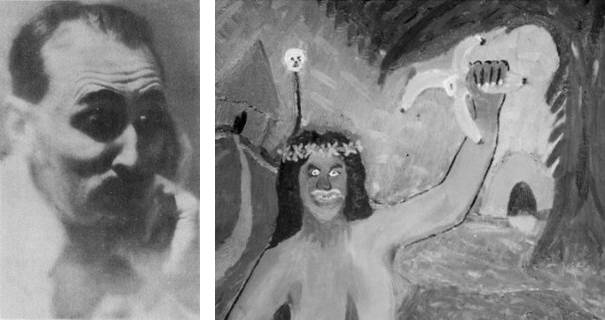

In 1924, irritated with the undiscerning faddishness of modern art criticism, Los Angeles novelist Paul Jordan Smith “made up my mind that critics would praise anything unintelligible.”

So he assembled some old paint, a worn brush, and a defective canvas and “in a few minutes splashed out the crude outlines of an asymmetrical savage holding up what was intended to be a star fish, but turned out a banana.” Then he slicked back his hair, styled himself Pavel Jerdanowitch, and submitted Exaltation to a New York artist group, claiming a new school called Disumbrationism.

The critics loved it. “Jerdanowitch” showed the painting at the Waldorf Astoria gallery, and over the next two years he turned out increasingly outlandish paintings, which were written up in Paris art journals and exhibited in Chicago and Buffalo.

He finally confessed the hoax to the Los Angeles Times in 1927. Ironically, “Many of the critics in America contended that since I was already a writer and knew something about organization, I had artistic ability, but was either too ignorant or too stubborn to see it and acknowledge it.” Can an artist found a school against his will?

“The uglier a man’s legs are, the better he plays golf. It’s almost a law.” — H.G. Wells

In 1989, Jules Verne’s great-grandson opened a disused family safe and found a forgotten manuscript. Composed in 1863, Paris in the Twentieth Century imagines the remote future of August 1960 — a world illuminated by electric lights in which people drive horseless carriages powered by internal combustion and ride in automatic, driverless trains.

In Verne’s vision, the citizens of Paris use copiers, calculators, and fax machines; inhabit skyscrapers equipped with elevators and television; and execute their criminals in electric chairs. Twenty-six years before the Eiffel Tower was erected, Verne described “an electric lighthouse, no longer much used, [that] rose into the sky to a height of 152 meters. This was the highest monument in the world, and its lights could be seen, forty leagues away, from the towers of Rouen Cathedral.”

Verne’s publisher had returned the manuscript because he found it too dark — in addition to the city’s technological wonders, it describes overcrowding, pollution, the dissolution of social institutions, and “machines advantageously replacing human hands.”

“No one today,” he had written, “will believe your prophecy.”

hystricine

adj. pertaining to porcupines

In a certain library, no two books contain the same number of words, and the total number of books is greater than number of words in the largest book.

How many words does one of the books contain, and what is it about?