214358976 = (3 + 6)2 + (4 + 7)8 + (5 + 9)1

Author: Greg Ross

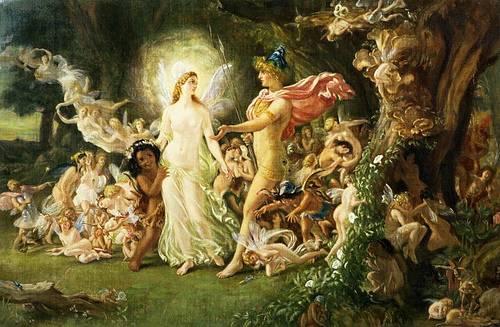

Theater Reports

In reviewing a Royal Shakespeare Company production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream for the New York Times in 1970, Clive Barnes found “David Waller’s virile bottom particularly splendid.”

He’d intended to capitalize “bottom.”

In 1915, Woodrow Wilson escorted his fiancee, Edith Galt, to the theater. The Washington Post reported that he “spent most of his time entering Mrs. Galt.”

That should have read entertaining — though presumably she would have been entertained either way.

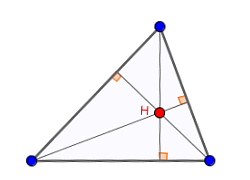

“Triangle Rhyme”

Although the altitudes are three,

Remarks my daughter Rachel,

One point’ll lie on all of them:

The orthocenter H’ll.

By mathematician Dwight Paine of Messiah College, 1983.

(Further recalcitrant rhymes: month, orange. W.S. Gilbert weighs in.)

“‘Declined With Thanks’ in Chinese”

The following is said to be an exact translation of the letter sent by a Chinese editor to a would-be contributor whose manuscript he found it necessary to return: ‘Illustrious brother of the sun and moon: Behold thy servant prostrate before thy feet. I kowtow to thee, and beg that of thy graciousness thou mayst grant that I may speak and live. Thy honored manuscript has deigned to cast the light of its august countenance upon us. With raptures we have perused it. By the bones of my ancestors, never have I encountered such wit, such pathos, such lofty thought. With fear and trembling I return the writing. Were I to publish the treasure you sent me, the emperor would order that it should be made the standard and that none be published except such as equaled it. Knowing literature as I do, and that it would be impossible in ten thousand years to equal what you have done, I send your writing back. Ten thousand times I crave your pardon. Behold my head is at your feet. Do what you will. Your servant’s servant. The Editor.’

— The Literary World, March 23, 1895

Unquote

“This is the biggest fool thing we have ever done. The bomb will never go off, and I speak as an expert in explosives.” — Admiral William D. Leahy to Harry Truman, 1945

Air Ball

The Matterhorn at Disneyland contains a basketball goal. Near the top of the mountain is a small preparation room used by the “mountaineers” who are sometimes seen scaling the exterior. The climbers installed a hoop and backboard so they could pass the time during bad weather.

The Matterhorn space is too cramped for a full game — for that you’ll need to visit the Supreme Court.

“Counting a Million in a Month”

The London Post says a wager came off, the terms of which were as follows. I will bet any man one hundred pounds, that he cannot make a million strokes, with pen and ink, within a month. They were not to be mere dots or scratches, but fair down strokes, such as form the child’s first lesson in writing. A gentleman accepted the challenge. The month allowed was the lunar month of only twenty-eight days; so that for the completion of the undertaking, an average of thirty-six thousand strokes a day was required. This, at sixty a minute, or three thousand six hundred an hour–and neither the human intellect nor the human hand can be expected to do more–would call for ten hours’ labor in every four and twenty. With a proper feeling of the respect due to the Sabbath, he determined to abstain from his work on the Sundays. By this determination he diminished by four days the period allowed him, and at the same time, by so doing, he increased the daily average of his strokes to upwards of forty-one thousand. On the first day he executed about fifty thousand strokes; on the second, nearly as many. But at length, after many days, the hand became stiff and weary, the wrist swollen, and it required the almost constant attendance of some assiduous relation or friend, to besprinkle it, without interrupting its progress over the paper, with a lotion calculated to relieve and invigorate it. On the twenty-third day, the million strokes, and some thousands over, were accomplished; and the piles of paper that exhibited them testified, that to the courageous heart, the willing hand and the energetic mind, hardly anything is impossible.

— Francis Channing Woodworth, American Miscellany of Entertaining Knowledge, 1852

Spine Appeal

Robert Benchley kept a special shelf of books that he favored for their titles:

- Forty Thousand Sublime and Beautiful Thoughts

- Success With Small Fruits

- Keeping a Single Cow

- Bicycling for Ladies

- Diseases of the Sweet Potato

- Talks on Manure

- Ailments of the Leg

In a review of the New York City telephone directory, he wrote, “The weakness of plot is due to the great number of characters which clutter up the pages. The Russian school is responsible for this.”

Blue Cold

On March 1, 1934, a scientist at New Hampshire’s already-odd Mount Washington observatory was digging in the snow before a garage when he was shocked to see that the holes he had dug “were promptly filled with deep blue light.”

Investigating, the man confirmed that the light could not be a “reflection from the sky or of bacteria collecting on the snow.” But no explanation was ever found, and no blue light has been reported since.

(Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 1934)

Sotto Voce

‘Wordsworth,’ said Charles Lamb, ‘one day told me that he considered Shakespeare greatly overrated. “There is an immensity of trick in all Shakespeare wrote,” he said, “and people are taken in by it. Now if I had a mind I could write exactly like Shakespeare.” So you see,’ proceeded Charles Lamb quietly, ‘it was only the mind that was wanting.’

— Frank Leslie’s Ten Cent Monthly, December 1863