Another reversible face, this one by British artist Rex Whistler (1905–1944).

Another reversible face, this one by British artist Rex Whistler (1905–1944).

The approach to Macon, Georgia’s 2012 International Cherry Blossom Festival was much safer than it appeared.

Artist Tracy Lee Stum’s anamorphic sidewalk painting took two days to create.

A digital animation by Catherine Leah Palmer.

Francesco Queirolo’s 1754 sculpture Release From Deception depicts an angel releasing a fisherman from a net.

Unbelievably, the entire piece was carved from a single block of marble.

Historian Giangiuseppe Origlia called it “the last and most trying test to which sculpture in marble can aspire.”

See The Veiled Virgin and Folds of Stone.

After several delusional episodes, seamstress Agnes Richter was institutionalized at the University of Heidelberg Psychiatric Clinic in 1893, at age 49. While performing the needlework expected of female patients, she sewed a diary of sorts into a remarkable jacket pieced together of wool and linen. “Writing” in a now-obsolete German script, she recorded brief, enigmatic expressions reflecting life in a psychiatric hospital: I wish to read, I am not big, I plunge headlong into disaster. Her laundry number, 583, appears several times, apparently to ensure that the jacket was not lost during cleaning.

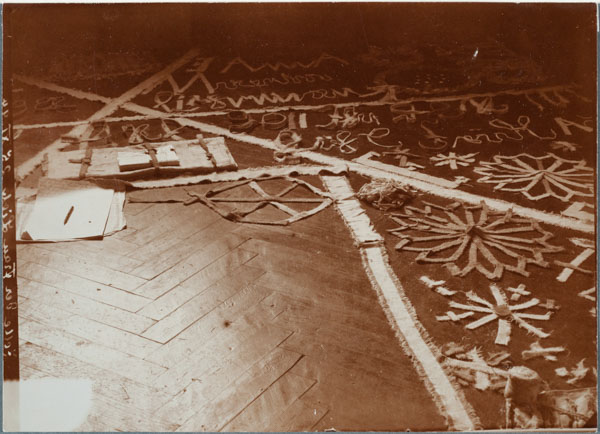

Another patient, Mary Lieb, institutionalized periodically at Heidelberg for mania, would sometimes decorate the floors of various rooms with patterns of cloth strips. The warders found some of these remarkable enough to photograph (below). Physician Hans Prinzhorn included some of the photographs in his collection of the art of the insane, and the images have survived to the present day as strangely vivid marks of an inscrutable self-expression.

“The patterns are extraordinary, comprising rows of starbursts (or perhaps flowers), letters, crosses, geometric patterns, and sometimes intricate curved figures,” writes Lyle Rexer in How to Look at Outsider Art. “Their purpose and organization are unclear, but like much outsider art, the work appears to be a combination of decoration and communication, an attempt to reorder the space ‘from the ground up,’ visually transform it, and invest it with new significance.” What it means only Lieb knew.

In November 1985, a couple walked into an art museum in Tucson, Arizona. While the woman chatted with a security guard, the man disappeared briefly upstairs, and then the pair departed. Then the guard discovered that Willem de Kooning’s painting Woman-Ochre was missing — it had been cut out of its canvas.

More than 30 years later, in 2017, retired New York speech pathologist Rita Alter passed away in the little town of Cliff, N.M., five years after her husband, Jerry, a former schoolteacher. In their bedroom was the missing de Kooning, in a position that was visible only when the door was closed. The painting appeared to have been reframed only once in the 31 years it had been missing, suggesting that it had had only one owner in that time.

Had the Alters stolen the painting? They were admirers of de Kooning and had been in Tucson the day before the theft. But such a crime seems vastly out of character for the retiring couple. “[They wouldn’t] risk something as wild and crazy as grand larceny — risk the possibility of winding up in prison, for God’s sake — they wouldn’t do that,” Rita’s sister told the New York Times.

Had the pair then bought the painting from a third party? That seems impossible too — it was worth an estimated $160 million. Perhaps the painting’s authenticity had been forgotten by the time of the transaction, so that both buyer and seller thought it was a copy? How could that have come about?

Jerry Alter once published a story in which a woman and her granddaughter steal an emerald from a museum and keep it on private display, “where two pairs of eyes, exclusively, are there to see.” Is that a coincidence? A veiled admission?

We may never know. The FBI’s case remains open.

(Thanks, Daniel.)

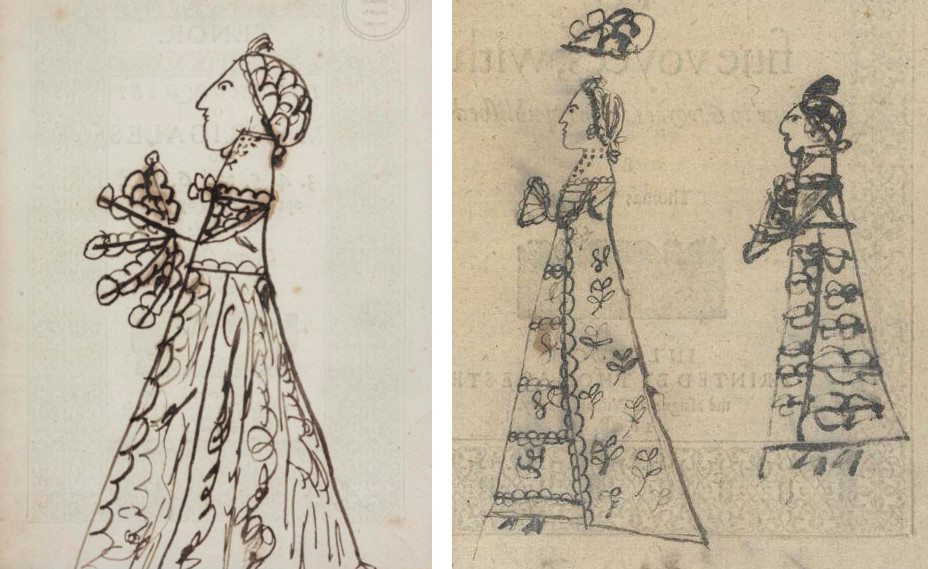

This is charming: Looking for a place to practice her drawing one day, an anonymous child in the 1700s chose the blank spaces in a music book. In doing so, she made herself immortal, as the music is now held in university collections.

The figure at left is scrawled in John Wilbye’s Second Set of Madrigales, now at the Royal Academy of Music; the one on the right is in Thomas Weelkes’ Balletts and Madrigals at Harvard. Drawings and handwriting exercises apparently by the same child appear in music books at UCLA, Huntington Library, and the University of Illinois. (The drawings all appear in tenor books, which suggests that these copies had been bound in one volume when the girl drew the pictures.)

The child’s identity is unknown, although the name Eliza Richardson accompanies one practice alphabet. She seems to be drawing the same woman consistently, recognizable by her prominent nose, strong chin, and thick neck. It’s not clear when the drawings were made, but the woman appears to be wearing a sack-back gown, a style that was most popular between 1720 and 1770. According to Durham University music professor David Greer, “The dense patterns, small cap, and closely dressed hairstyle suggest the early part of this period.” But I believe that’s all we know.

(David Greer, Manuscript Inscriptions in Early English Printed Music, 2015.)

For a 2005 retrospective on Salvador Dalí, the Philadelphia Museum of Art painted its front steps.

“I have never taken any drugs,” Dalí once said. “Dalí is the drug.”

When [a man] puts a thing on a pedestal and calls it beautiful, he demands the same delight from others. He judges not merely for himself, but for all men, and then speaks of beauty as if it were a property of things. Thus he says that the thing is beautiful; and it is not as if he counts on others agreeing with him in his judgment of liking owing to his having found them in such agreement on a number of occasions, but he demands this agreement of them. He blames them if they judge differently, and denies them taste, which he still requires of them as something they ought to have; and to this extent it is not open to men to say: Every one has his own taste.

— Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, 1790