Art

A One-Sided Score

Conductor and musical lexicographer Nicolas Slonimsky composed a “Möbius Strip Tease” in 1965, while he was teaching at UCLA. The text reads:

Ach! Professor Möbius, glörious Möbius

Ach, we love your topological,

And, ach, so logical strip!

One-sided inside and two-sided outside!

Ach! euphörius, glörius Möbius Strip-Tease!

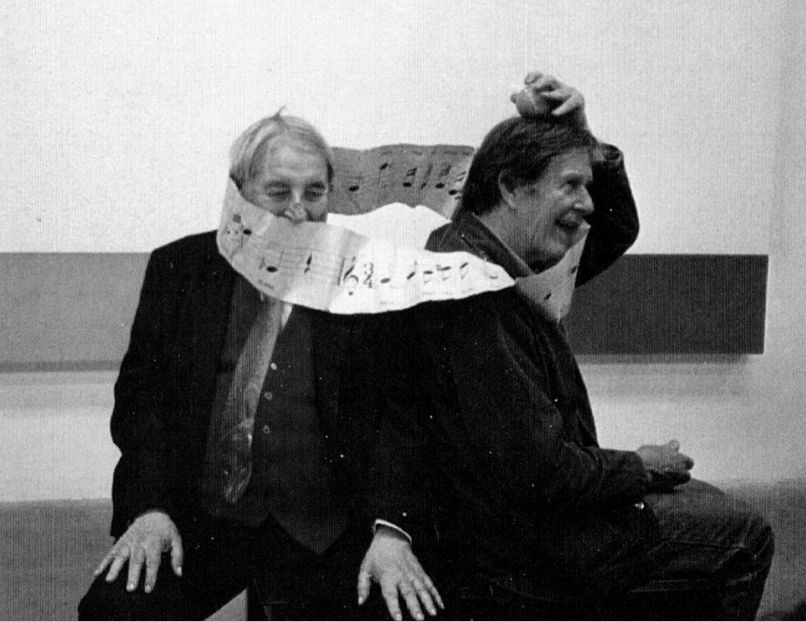

Slonimsky described the piece as “a unilateral perpetual rondo in a linearly dodecaphonic vertically consonant counterpoint.” The instructions on the score read: “Copy the music for each performer on a strip of 110-b card stock, 68″ by 6″. Give the strip a half twist to turn it into a Möbius strip.” In performance the endless score rotates perpetually around each musician’s head. (That’s Slonimsky above, trying it out with John Cage.)

The score is here if you’d like to try it yourself. Be careful.

Nocturne

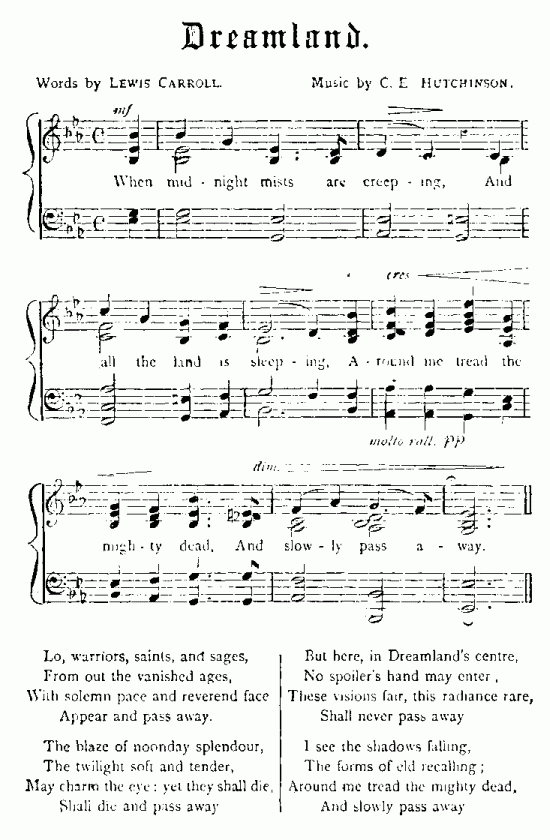

Here’s an oddity: In 1882 Lewis Carroll collaborated on a song with the dreaming imagination of his friend the Rev. C.E. Hutchinson of Chichester. Hutchinson had told Carroll of a strange dream he’d had:

I found myself seated, with many others, in darkness, in a large amphitheatre. Deep stillness prevailed. A kind of hushed expectancy was upon us. We sat awaiting I know not what. Before us hung a vast and dark curtain, and between it and us was a kind of stage. Suddenly an intense wish seized me to look upon the forms of some of the heroes of past days. I cannot say whom in particular I longed to behold, but, even as I wished, a faint light flickered over the stage, and I was aware of a silent procession of figures moving from right to left across the platform in front of me. As each figure approached the left-hand corner it turned and gazed at me, and I knew (by what means I cannot say) its name. One only I recall — Saint George; the light shone with a peculiar blueish lustre on his shield and helmet as he turned and slowly faced me. The figures were shadowy, and floated like mist before me; as each one disappeared an invisible choir behind the curtain sang the ‘Dream music.’ I awoke with the melody ringing in my ears, and the words of the last line complete — ‘I see the shadows falling, and slowly pass away.’ The rest I could not recall.

He played the melody for Carroll, who wrote a suitable lyric of five verses. Hutchinson disclaimed writing the music, but if he didn’t … who did?

(From Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll, 1898.)

11/24/2021 UPDATE: Reader Paul Sophocleous provided this MIDI file of the published music. (Thanks, Paul.)

Inspiration

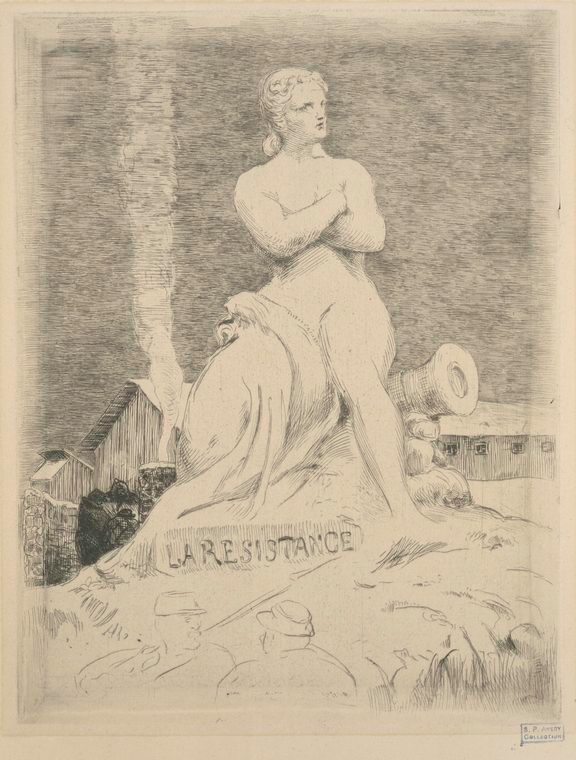

During a lull in the Prussian attack on Paris in December 1870, the Seventh Company of the French National Guard spent a few hours building a “museum” of snow on the southern edge of the city. Among them was 29-year-old sculptor Alexandre Falguière, who spent three hours crafting La Statue de la Résistance, a nine-foot emblem of French resistance in the form of a defiant woman atop a cannon. Félix Philippoteaux sketched the snow woman, Théophile Gautier wrote an essay, Théodore de Banville published a poem, Félix Bracquemond made an etching, and Faustin Betbeder produced a series of lithographs, but none of these captured the essence of the original. Falguière promised to make a permanent version in plaster or marble, but it never appeared. Critic H. Galli wrote in L’Art français in 1895:

As soon as Falguière was back in his studio, he took up his modeling knife, but he sought, worked, and suffered in vain. None of his maquettes had the proud allure, the poetry of his snow statue; he destroyed them. The capitulation, the dismemberment of France, and then the awful civil war had, alas, dissipated his last hopes. The inspiration was dead.

“Recapturing that magic would prove to be impossible for the unflagging Falguière,” writes Bob Eckstein in The History of the Snowman. “Eventually he created many variations in wax, plaster, terra cotta, and bronze, ranging in size from two to four feet high, all less successful than the original snow sculpture. Falguière could never duplicate the spontaneity and urgency of that long-gone snow woman. That moment had passed and had melted along with his original masterpiece.”

Extra Credit

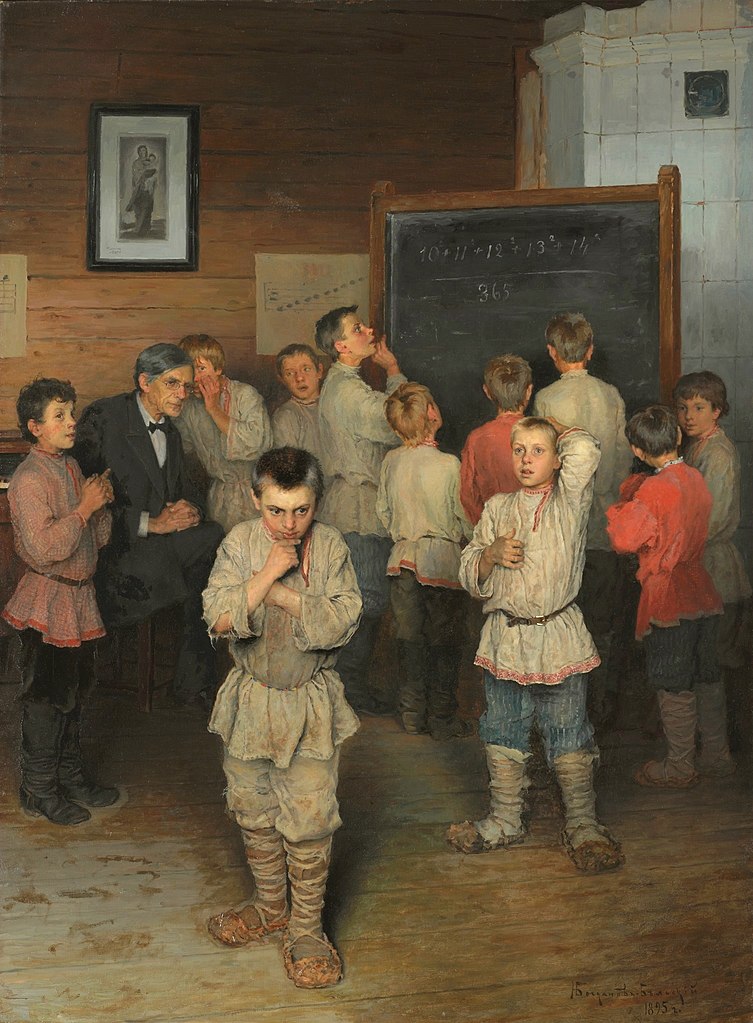

The boys in Nikolay Bogdanov-Belsky’s 1895 painting Mental Arithmetic are having a difficult time solving the problem on the board:

As it happens, there’s a simple solution: Both (102 + 112 + 122) and (132 + 142) are equal to 365, so the answer is simply (365 + 365) / 365, or 2. They’ll figure it out.

Free Enterprise

Charging Bull, the bronze sculpture that’s become a ubiquitous symbol of Wall Street, was not commissioned by New York City or anyone in the financial district. Artist Arturo Di Modica spent $360,000 to create the three-ton statue, trucked it to Lower Manhattan, and on Dec. 15, 1989, left it in front of the New York Stock Exchange as a Christmas gift to the people of New York. Police impounded it, but after a public outcry the city decided to install it two blocks south of the exchange.

Since New York doesn’t own it, technically it has only a temporary permit to remain on city property. But after 32 years, it appears to have become a permanent fixture.

Freeze!

Here’s a lost art: The tableau vivant, or “living picture,” was a form of popular entertainment in which the actors took up poses but did not speak or move. (This one presents the original cast of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty.)

In our era of ubiquitous video it’s hard to remember how important this was — it formed a sort of living bridge between painting and the stage, representing dramatic moments in three dimensions that could be studied and admired as part of the real world. Sometimes stories were told through a series of connected tableaux, a technique that would lead eventually to modern storyboards and comic strips.

The form also inspired a curious practice: Censorship laws in Britain and the United States forbade actresses to move onstage when they were unclothed, so exhibitors began to present nude women in tableaux vivants, imitating works of classical art. The presenters could claim that this was edifying, the audiences got their erotic entertainment, and the production was allowed to go on — so long as the women didn’t move.

The Chatsworth Violin

Visitors to Chatsworth House in Derbyshire are struck at the illusion of a violin hanging on a door in the State Music Room. The peg is real, but the violin is not — it’s a very convincing trompe l’oeil painting executed by the Dutch artist Jan van der Vaardt.

It’s thought to have been painted around 1723. In his Anecdotes of Painting (1762), Horace Walpole writes, “In old Devonshire-house in Piccadilly, he painted a violin against a door that deceived every body. When the house was burned, this piece was preserved, and is now at Chatsworth.”

Footwork

Dance has a distinctive place among the performing arts. Dancers don’t “cause” a dance in the same way that musical instruments cause music. Rather, dancers are the dance — their movements instantiate it.

“You can’t describe a dance without talking about the dancer,” wrote American choreographer Merce Cunningham. “You can’t describe a dance that hasn’t been seen, and the way of seeing it has everything to do with the dancers.” A work of dance might be recorded abstractly in notation, but it’s the performance that realizes it; you can’t really encounter a dance without seeing it performed.

With that in mind, suppose that The Nutcracker is performed simultaneously in two different cities. If a dance work is fully realized only in performance, then can we really say that Performance A presents the same artwork as Performance B? If not, then what is The Nutcracker?

A related puzzle: Does a dance work last forever? It certainly has a beginning in time; does it have an end, if, say, it’s forgotten? Our species will one day become extinct — when that happens, will The Nutcracker cease to exist?

(Jenny Bunker, et al., Thinking Through Dance, 2013; Graham McFee, The Philosophical Aesthetics of Dance, 2011.)

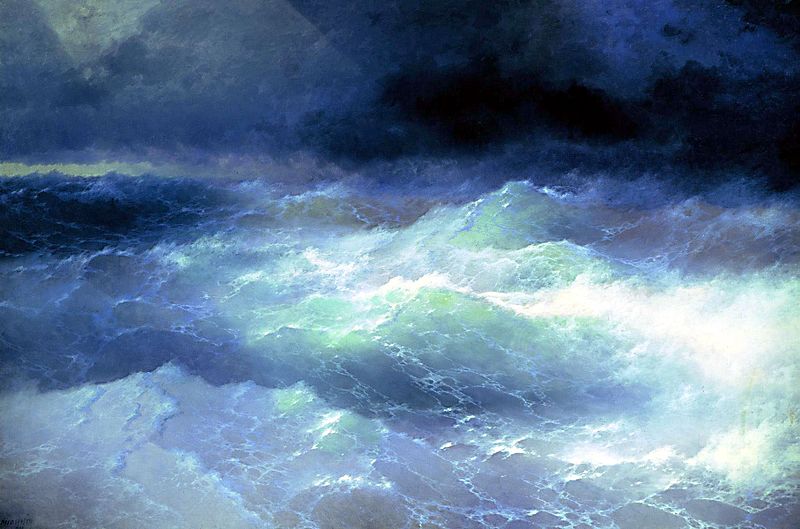

The Mozart of the Sea

Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817-1900) earned fame throughout Russia for his astonishingly realistic seascapes, which capture the expressive quality of ocean waters, and in particular the play of sunlight and moonlight on surging waves. More than half of the artist’s 6,000 canvases are devoted to his fascination with moving water.

Remarkably, these were painted from memory, far from the sea. “We can perfectly well understand that when he painted The Ninth Wave or The Wreck, he had no need to watch the ever-shifting colour and movement of the great waters as he worked, for these pictures are poems in which the artist has concentrated an amplitude of observation and experience,” wrote Rosa Newmarch in 1917. “We realize that their impressive, haunting grandeur is no more spontaneous than the impressiveness of many a great sonnet; they are rather the aftermath of his passion for the sea.”

His successes made him equally popular among the people and among his fellow artists. Ivan Kramskoi wrote, “Aivazovsky is — no matter who says what — a star of first magnitude, and not only in our [country], but also in history of art in general.” And the saying “worthy of Aivazovsky’s brush” was used in Russia to describe anything ineffably lovely.

Wikimedia Commons has a collection of his seascapes.