An anamorphic portrait of Isaac Asimov, by Marcos Sachs.

More at Sachs’ YouTube channel.

An anamorphic portrait of Isaac Asimov, by Marcos Sachs.

More at Sachs’ YouTube channel.

Is this typeface, by artist and calligrapher Dmitry Lamonov, uppercase or lowercase? It’s both!

He’s done the same thing in Cyrillic.

This is charming somehow: a detailed portrait of a place that doesn’t exist. During the Cold War, U.S Army cryptologist Lambros D. Callimahos devised a “Republic of Zendia” to use in a wargame for codebreakers simulating the invasion of Cuba. (Callimahos’ maps of the Zendian province of Loreno are below; click to enlarge.)

The Zendia map now hangs on the wall of the library at the National Cryptologic Museum. The “Zendian problem,” in which cryptanalysts students were asked to interpret intercepted Zendian radio messages, formed part of an advanced course that Callimahos taught to NSA cryptanalysts in the 1950s. Graduates of the course were admitted to the “Dundee Society,” named for an empty marmalade jar in which Callimahos kept his pencils.

08/02/2025 UPDATE: Apparently they speak Esperanto in Zendia, or at least their cartographers do. “Respubliko” is Esperanto for “Republic,” “Bovinsulo” and “Kaprinsulo” are “Cow-Island” and “Goat-Island”, and so on. (Thanks, Ed and David.)

The last movement of Mahler’s sixth symphony calls for the sound of a hammer, which the composer indicated should be “brief and mighty, but dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character (like the fall of an axe).” (The two blows represent the death of Mahler’s daughter Maria and the diagnosis of his heart condition.)

Because no recognized instrument exists to fulfill this function, symphonies have had to devise their own solutions, often striking a wooden box or bass drum with a mallet or sledgehammer. Houston Symphony percussionist Brian Del Signore built a 22-pound custom hammer and a wooden box to receive the blow.

Given names of the 11 children of Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Russell of Vinton, Ohio, 1972:

“Mother did it, but I don’t know why,” Laur told UPI. “She would take names from the Bible and other books and compare them until they came out that way.”

Bonus palindrome item: Volume 1, Issue 5 of Alan Moore’s graphic novel Watchmen, titled “Fearful Symmetry,” is a deliberately contrived visual palindrome, not just in structure but often within individual panels (designed by artist Dave Gibbons). Pedro Ribeiro shows the correspondences here.

Austrian artist Thomas Medicus’ 2014 anamorphic sculpture Emulsifier arranges 160 hand-painted glass strips to present each of four different images, depending on the viewer’s perspective.

Head Instructor, below, uses the same technique. More at his website.

This bookcase, in Bologna’s International Music Museum and Library, is itself a work of art — the doors are paintings depicting shelves of music books, rendered by Baroque artist Giuseppe Crespi.

Below: In 2014, designer József Páhy devised this bookish façade for a housing estate in Kazincbarcika, Northern Hungary. That’s a teddy bear on the bottom shelf.

This building, at 1643 Plaza de los Carros in Madrid, is half illusion — the façade on the left, including the windows, ironwork, awnings, even the residents, is all a trompe-l’œil mural by artist Alberto Pirrongelli.

In this 1515 painting, The Adoration of the Christ Child, the angel immediately to Mary’s left appears to bear the characteristic facial features of Down syndrome (click to enlarge). This would make the painting one of the earliest representations of the syndrome in Western art.

Unfortunately, little is known about it. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which owns it, has identified the painter only as a “follower of Jan Joest of Kalkar.” Researchers Andrew Levitas and Cheryl Reid have suggested that the painting may indicate that individuals with Down syndrome were not regarded as disabled in medieval society. But so little is known about the work or its creator that it’s hard to establish a reliable conclusion.

“After all the speculations, we are left with a haunting late-medieval image of a person with apparent Down syndrome with all the accouterments of divinity. It is impossible to know whether any disability had been recognized or whether it simply was not relevant in that time and place.”

(Andrew S. Levitas and Cheryl S. Reid, “An Angel With Down Syndrome in a Sixteenth Century Flemish Nativity Painting,” American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 116:4 [2003], 399-405.) (Thanks, Serge.)

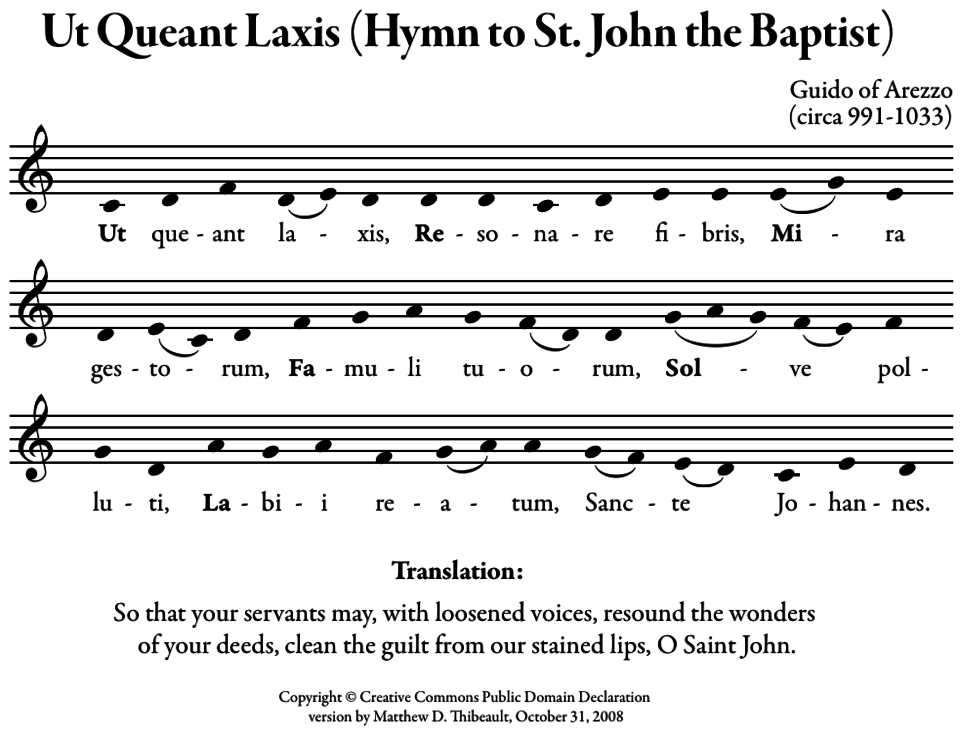

Where did the familiar syllables of solfège (do, re, mi) come from? Eleventh-century music theorist Guido of Arezzo collected the first syllable of each line in the Latin hymn “Ut queant laxis,” the “Hymn to St. John the Baptist.” Because the hymn’s lines begin on successive scale degrees, each of these initial syllables is sung with its namesake note:

Ut queant laxīs

resonāre fibrīs

Mīra gestōrum

famulī tuōrum,

Solve pollūti

labiī reātum,

Sancte Iohannēs.

Ut was changed to do in the 17th century, and the seventh note, ti, was added later to complete the scale.